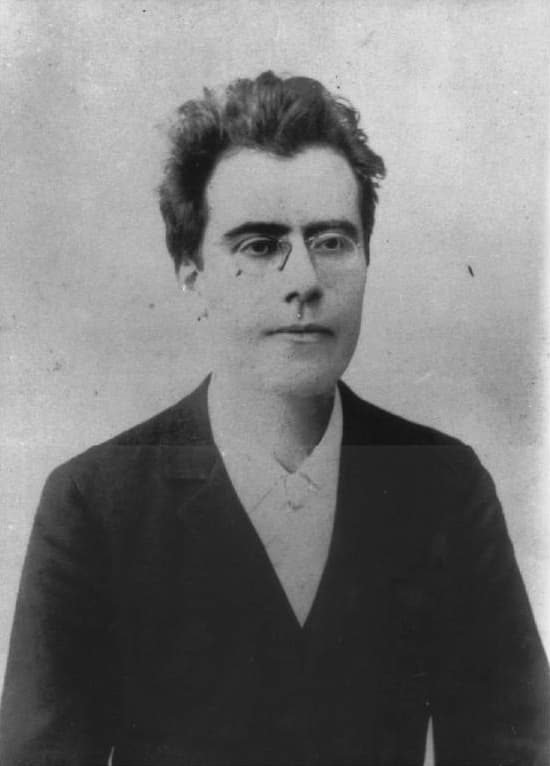

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) obtained his diploma from the Vienna Conservatory at the age of 18, and he certainly had to make an important decision on his further path in music. One year before, he had completely given up the idea of a career as a concert pianist, and conducting an orchestra wasn’t even on the radar. In fact, between 1878 and 1880, he was completely immersed in his creative work and forced himself to live on a small allowance sent by his family. However, things did not go smoothly. As he told a friend, “At the conservatoire I never finished a single score. I usually stopped after the first or second movement, occasionally after the third… not because I was impatient to start another but because, before even finishing my work, I was no longer satisfied with it. I had already moved beyond it.”

Opus 1

The young Gustav Mahler

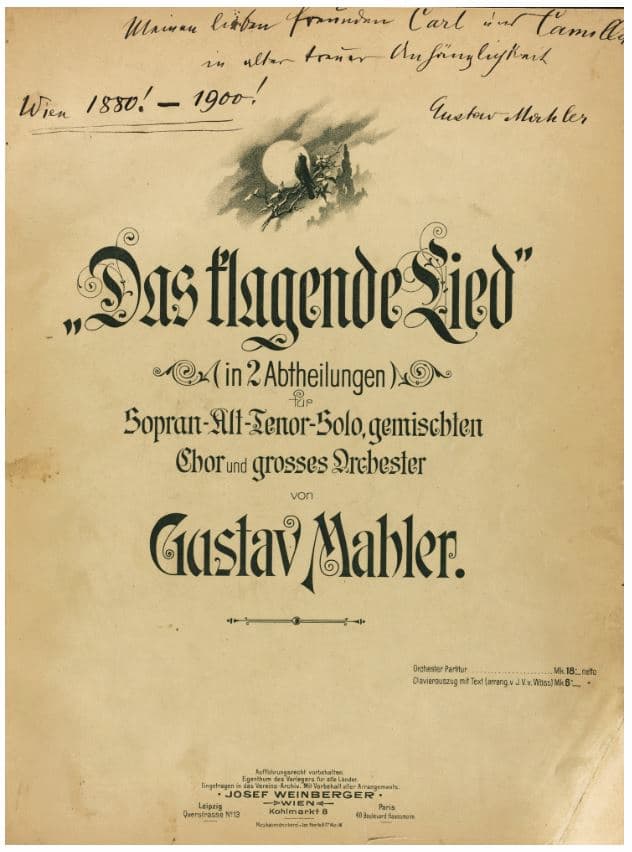

However, one of the pieces Mahler started during his final year at the Conservatory was a work Mahler himself called “the first work in which I found myself as Mahler.” That particular works was a cantata Das klagende Lied (Song of Lamentation), and it would be the work Mahler himself considered his Opus 1. Mahler had originally intended to write a fairy-tale opera in cooperation with his friend, Hugo Wolf, but that idea was not realised. In 1877, Mahler had studied Middle High German at the University of Vienna, and also attended lectures on Old High German literature. The choice of subject grew from an intellectual and artistic ambience that was dominated by a late Romanticism and historicism preoccupied with the German Middle Ages. Of equal importance was the operatic influence steeped in Nordic legend and mythology flowing from the pen of Richard Wagner.

Libretto Sources

Gustav Mahler’s Das klagende Lied

Following the example set by Wagner, Mahler wrote the libretto before composing the music, and he relied on a number of literary works to fashion his poem. We find motifs derived from an anthology of fairytales by Ludwig Bechstein and a story entitled “Das klagende Lied,” and another taken from a Brothers Grimm tale, “Der singende Knochen” (The Singing Bone). In Part I of Mahler’s poem, a beautiful yet scornful queen offers herself in marriage to the man who can find a special red flower in the forest. Two brothers, one kind and chivalrous, the other wicked and blasphemous, venture into the forest to find the elusive flower. The gallant brother quickly finds the flower, and he puts it in his cap and lies down to sleep. When the evil brother comes upon the scene, he kills his sibling with his sword, takes the flower and buries his brother beneath a willow tree.

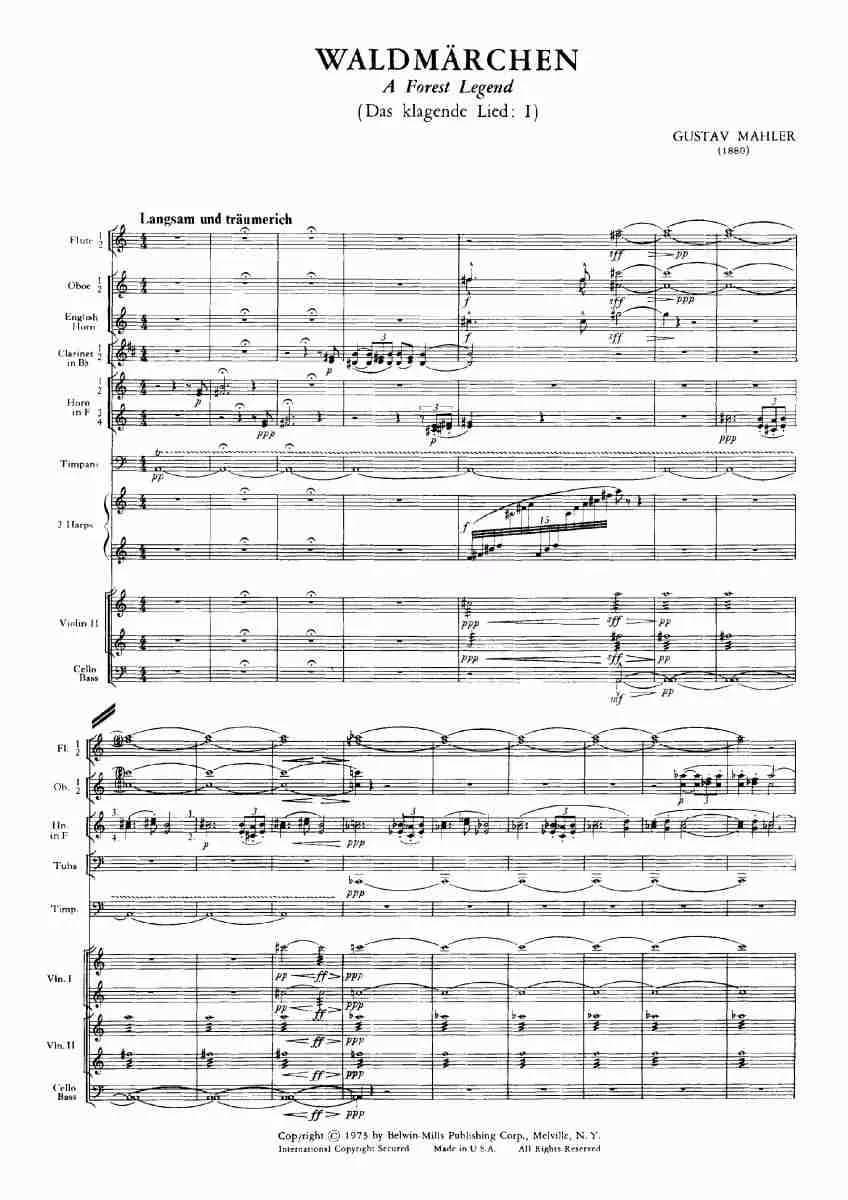

Gustav Mahler: Das klagende Lied (Song of Lamentation), Part 1 “Waldmärchen” (Forest Legend) (Ernst Haefliger, tenor; Elisabeth Söderström, soprano; London Symphony Orchestra; London Symphony Chorus; Pierre Boulez, cond.)

The Plot

In Part II “Der Spielmann” (The Minstrel), a wandering minstrel meanders through the forest and stumble across a bleached bone in the shade of a willow tree. The minstrel carves it into a flute, and the instrument takes on the voice of the murdered brother and laments and details his unfortunate death. The minstrel now takes the flute to the great hall of the King, resolved to find the queen and inform her of what has happened. In the concluding Part III, “Hochzeitsstück” (Wedding Piece), the minstrel arrives at the castle during the wedding celebration of the queen and the older brother. He plays the flute, which retells the story of the murder. Angered, the older brother scornfully seizes the flute and puts it to his lips. However, the singing bone now accuses him, “Oh brother, it was you who murdered me.” Pandemonium ensues, the queen collapses to the ground, the guests run away in horror, and the castle begins to sink into the ground.

Beethoven Prize

Mahler’s Song of Lamentation – Forest Legend

Mahler completed the scoring in November 1880 and reports, “My fairy-tale is finished at long last truly a child of sorrow, more than a whole Year’s labour. But it has turned out to be worth it. The next thing is to use all means at my disposal to get it performed.” However, this proved to be somewhat difficult. Mahler entered the work for the 1881 Beethoven Prize of 500 Gulden hosted by the Gesellschaft der Musikfeunde, and as he later wrote, “If the Conservatory jury, which included Brahms, Goldmark, Hanslick, and Richter had given me the Beethoven Prize for Das klagende Lied, my whole life would have taken a different course. Perhaps I would have been spared the whole vile operatic career.” To be sure, Brahms felt real hostility towards Bruckner’s students and disciples, especially Hans Rott, Hugo Wolf, and Gustav Mahler. As we all know, Rott went mad and died in an asylum, Wolf musically moved as far away from Brahms as possible, and Mahler was soon on his way to conduct opera in Laibach.

Revisions

After the rejection of his cantata, Mahler kept revisiting the score of Das klagende Lied over a number of years. The original three-movement version featured a bone flute scored for a boy’s voice and an off-stage band in the concluding two parts. The orchestration called for six harps and natural horns, but Mahler never heard this version. In an 1893 revision, Mahler jettisoned the first movement, deleted the off-stage band, reduced the harps from six to two, and cut the vocal soloists from eleven to four, completely eliminating the boy’s voices. Mahler made an additional revision in 1898 by reworking the off-stage band into the orchestral fabric and rewriting the balance between the soloist, chorus and orchestra. However, he never reinstated the opening “Forest Legend.”

Gustav Mahler: Das klagende Lied (Song of Lamentation), Part 2 “Der Spielmann” (The Minstrel) (Marina Shaguch, soprano; Michelle DeYoung, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Moser, tenor; Sergey Leiferkus, baritone; San Francisco Symphony Chorus; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

First Performance under Mahler

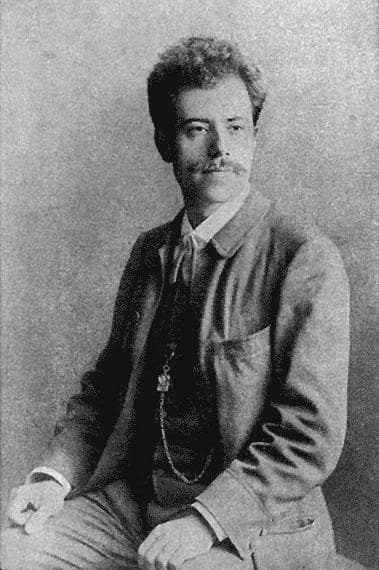

Gustav Mahler

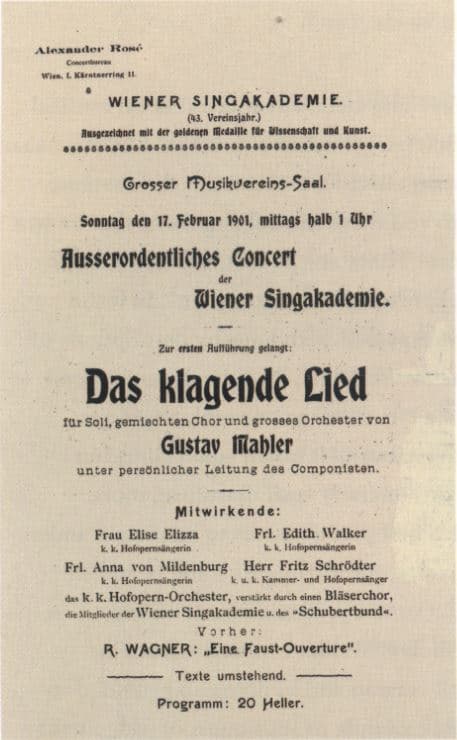

The two-movement version of Das klagende Lied was finally giving its first performance on 17 February 1901, during a special concert of the Wiener Singakademie. As it was written during a time “when I naively thought that the whole world would accept it and play it immediately,” Mahler explained, “it required numerous rehearsals.” Mahler himself was struck by the surprising originality of this youthful work, which “sprang from my brain fully equipped and finished.” As expected, however, the critics unanimously attacked this “eccentric work of youth.” They found it “shocking and subversion, with everything in the work, from its very length, its subject, the dividing part of the episodes…declared anomalies.” For some critics, the “choral writing was a crime against the nature of the voice.”

Hostile Critics

According to contemporary voices, the work contained only a “few rare moments of touching and authentic music, some remarkable and vividly defined moods… original but terribly laboured harmonies and orchestral experiments that reveal an unquiet spirit and a veritable cult of the ugly. Mahler created a flood of ugliness.” Mahler had intended a second performance with the same cast, but it was Mengelberg who presented the work in Amsterdam in 1906. The manuscript source of “Forest Legend” was discovered only in 1969 as part of Alma Mahler’s papers. The manuscript then passed into the hands of Yale University, and the first edition of all three movements was published in March 1997 by Universal Editions. The world premiere took place on 7 October 1997 in Manchester, England.

Restoration

Mahler’s premiere of Das klagende Lied

With the restoration of the first part and its original instrumentation and soloist, the cantata has returned to its original sequence of events. In performances today, however, you are likely to hear a mixed version, which is the one I have included in this blog as well. Bruckner and Wagner are alluded to in the first and concluding parts, but the central “Minstrel” contains distinctive Mahlerian music. Much of the opening paragraph, the motivic opening against the tremolo, “foreshadows Mahler’s later ability to conjure atmosphere less from melodies and themes than from wisps and ideas and sonorous effects.” Mahler ingeniously handles the enormous orchestra, and various leitmotifs clarify the dramatic situation and development. Yet there can be no doubt that Mahler had found a personal style and individual voice, one that musicians and critics were to resist well into the twentieth century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Gustav Mahler: Das klagende Lied (Song of Lamentation), Part 3 “Hochzeitsstück” (Wedding Piece) (Marina Shaguch, soprano; Michelle DeYoung, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Moser, tenor; Sergey Leiferkus, baritone; San Francisco Symphony Chorus; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)