Johannes Brahms’s carefully crafted music can be difficult for some listeners to immediately connect with. Sometimes it takes the memories of the colleagues who knew him best to paint a more human portrait of the man.

Ilona Eibenschütz

One incredible source of Brahmsian memories is pianist Ilona Eibenschütz.

Ilona Eibenschütz was a piano prodigy born in 1873 in Budapest. She studied with Clara Schumann for five years and spent time in Brahms’s social circle.

In 1952, at the age of seventy-nine, she gave an audio interview about her memories of Brahms.

Here are some of the most fascinating takeaways from her interview:

Ilona Eibenschütz talks and plays: Reminiscences of Brahms (1952)

1. Eibenschütz was ecstatic to meet Brahms, and he made a huge impression on her.

Eibenschütz said in the interview:

When I was thirteen years old, I came from Vienna, my home, to Frankfurt to study with Clara Schumann. A few months after my arrival, I met Brahms for the first time in Frau Schumann’s house. He was staying with her…

My enthusiasm was great, and when Frau Schumann introduced me to Brahms with a few warm words, I thought that nobody in the world could be happier than I.

She had just heard Brahms play in a performance of his C-minor trio, op. 101. The experience was unforgettable:

Never can I forget this performance, and the trio remained my favorite for life!

Brahms: Piano Trio in C minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello – I. Allegro engerico

2. Brahms and his circle loved performing chamber music for each other in small groups at home, with no audience.

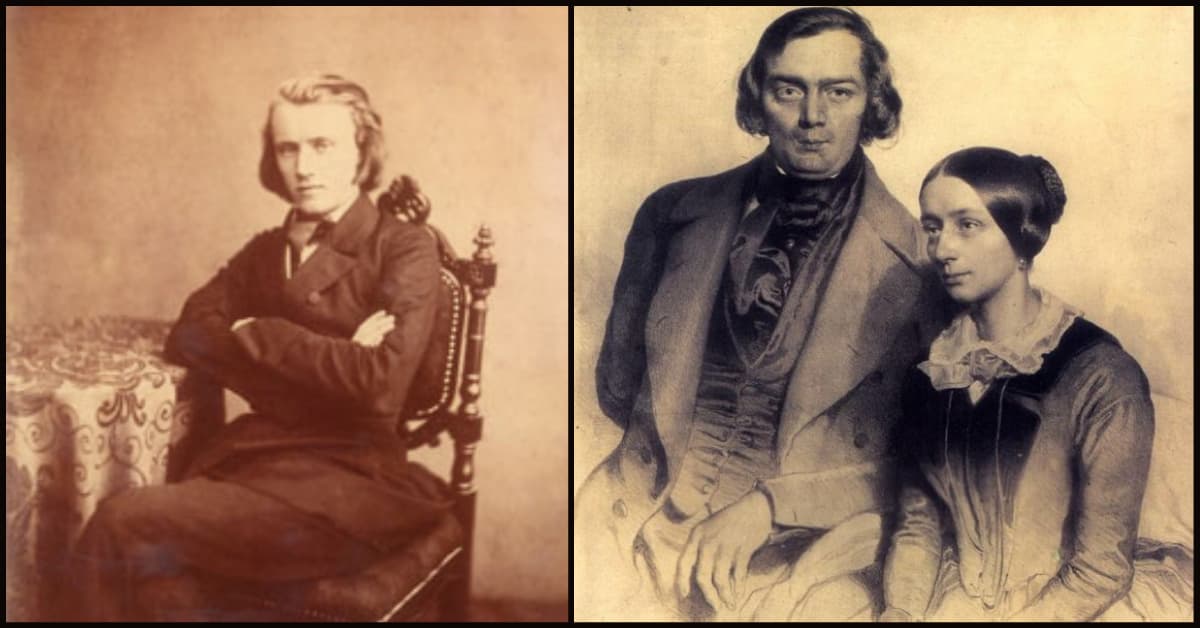

The young Johannes Brahms and the Schumanns

Eibenschütz recalled multiple tantalizing performances in the musicians’ homes.

One especially intriguing at-home program consisted of Ilona Eibenschütz (aged around 18) playing the Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 32, world-famous singing teacher Julius Stockhausen singing various Brahms songs, and Clara Schumann playing her late husband Robert Schumann’s Carnaval.

Another time, Eibenschütz played at a dinner party thrown by Johann Strauss II. She performed Brahms’s G-minor Piano Quartet with the renowned Kniesel Quartet for the assembled guests, while famous conductor Arthur Nikisch turned pages for her.

We played in high spirits with Brahms as a listener in a comfortable chair with a big cigar.

“Brahms liked music in small company,” she said.

That might be an argument for trying to catch Brahms performances in more intimate venues!

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 1 G-minor Op. 25

3. One way to befriend Brahms was to play well under pressure.

The Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien (“Society of Friends of Music in Vienna”) was a prestigious organisation founded in 1812.

Many if not most of its members were professional musicians, and they worked together to advance various musical causes in Vienna.

In the 1870s, Brahms was president for a few years. But even after he stepped down, he continued his association with the society.

Ilona Eibenschütz was once scheduled to give a recital there with cellist Friedrich Grützmacher. It was a nerve-wracking gig, performing in front of the greatest musicians in Vienna, one of the most musical cities in the world.

At the very last moment, after Eibenschütz had already performed works by Robert Schumann, Brahms, and Scarlatti, word came that Grützmacher would not be able to join her.

Instead of calling off the second half of the show, Brahms told Eibenschütz, presumably remembering her earlier performance, “Now do play the Op. 111 by Beethoven.”

With no preparation, Eibenschütz did.

She later recalled, I believe that from that moment, Brahms was my friend.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata no.32 in C minor Op.111

4. Brahms was genuinely interested in the career paths of young artists he admired…especially if they studied with Clara Schumann.

Ilona Eibenschütz

Eibenschütz said of the post-concert meal after her surprise performance:

At supper after the concert, I had to sit next to him. He wished to know all my plans and what Frau Schumann wanted me to do.

When the two crossed paths again, while summering in Brahms’s beloved summer vacation destination of Ischl, Austria, they talked about her career again.

I had been in Ischl a few days when one afternoon Brahms paid me a visit. It was a great moment for me and I felt very happy. I had to tell him all about London, everything interesting, especially that Mr. Arthur Chappell engaged me at once for four more concerts…

Nowhere else was he so happy.

By this time (the early 1890s), Brahms was an elder statesman of the art. Although he had no practical need to keep up with the career of up-and-coming artists, he retained a genuine, heartfelt interest in their career trajectories.

5. Brahms was deeply grateful when performers spent time studying and rehearsing his scores.

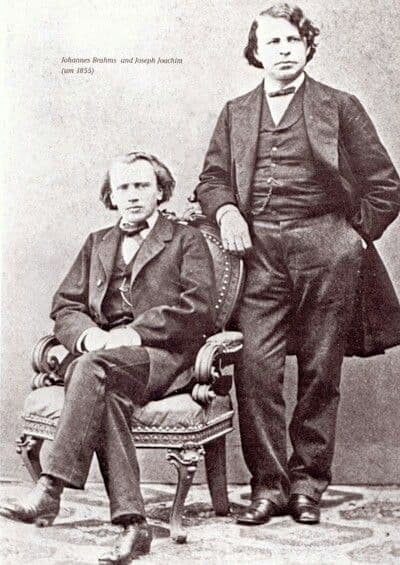

Brahms and Joachim, ca 1855

Eibenschütz once appeared with violinist (and Brahms’ friend) Joseph Joachim in London, playing a Beethoven piano trio.

A new string quintet by Brahms (his op. 111) was also on the program. This quintet has no piano part, so Eibenschütz just watched Joachim during rehearsal instead.

She was deeply impressed by how meticulously the great artist prepared Brahms’s work. Joachim had known Brahms for decades, but he was still treating the score with reverence.

I told Brahms how carefully Joachim had rehearsed his quartet, and what a splendid reception it met with. He was very pleased.

Brahms : String Quintet No.2 in G major, Op.111

6. Brahms hated it when people made a big deal over him.

Eibenschütz remembered:

A few days later, Brahms came to dinner with us. One o’ clock… He soon made it his habit to come to us one meal every week for dinner. He liked being with us because we made no fuss whatever with him.

7. Brahms was a huge fan of Johann Strauss II, the “Waltz King.”

Johann Strauss II also took summer vacations in Ischl. One time at a dinner party, his path crossed with Brahms’s, to both men’s delight. Strauss asked Brahms for his autograph.

According to Eibenschütz:

[Brahms] wrote a few bars of the famous Blue Danube waltz by Johann Strauss, and under it “unfortunately not by Johannes Brahms.”

8. Brahms expressed his affection for friends and loved ones through his music.

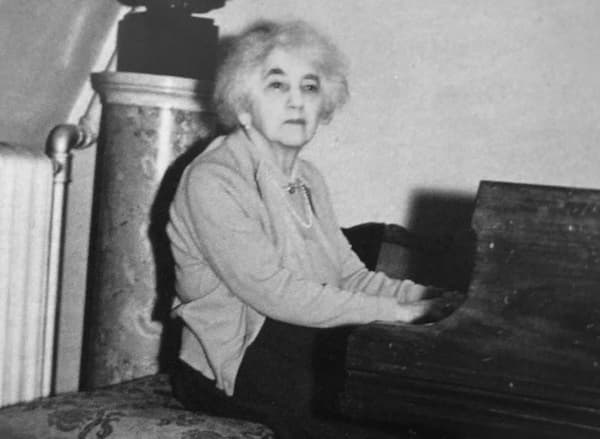

Ilona Eibenschütz, 1958

Eibenschütz told a touching story of how, in the summer of 1893, Brahms once said suddenly after dinner, “Oh, I want to play you a few exercises which I have just composed.”

She and Brahms went into the music room. Nobody else in the household was allowed to be present. Brahms began playing a set of piano pieces for her that would turn into the Op. 118 and 119.

Brahms – 6 Klavierstücke, Op. 118 (Murray Perahia)

He played…sometimes humming to himself, forgetting everything around him. His playing was altogether grand and noble, like his compositions. It was, of course, the most wonderful thing for me to hear these pieces, as nobody yet knew anything about them. I was the first to whom he played them.

When he finished playing, I was very excited and hardly knew what to say. I murmured only that I must write Frau Schumann about them at once.

He looked at me and said, “But you did not like them!”

“How can you possibly say such a thing to me?” I asked.

And he answered with a twinkle in his eye, “You did not ask da capo [“from the top” or “encore”] for a single piece!”

I had the presence of mind to say, “I want them all da capo, but not today.” He laughed. And a few days later, played them to me again.

A few months after, at the Monday Popular Concerts in London, I gave them their first public performance. Of course, I wrote to Frau Schumann about the Klavierstucke at once.

Years later, when the letters between her teacher and Brahms were published, Eibenschütz found a reference to the works she had premiered.

In a letter dated September 1892, she wrote to Brahms after a very sad misunderstanding, “So let us, dear Johannes, resume our friendship for which your new Klavierstücke, about which Ilona has written to me, affords the best opportunity, if you are willing. With sweet greetings in the old affectionate way, from your Clara.”

Brahms to Clara Schumann, Ischl, August 1893: “Yesterday your Ilona was here. And because she is yours, and your letter came, I played her all the pieces.”

Clara died in 1896, and Brahms died less than a year later in 1897.

Upon Brahms’s death, the twenty-year-old Ilona Eibenschütz’s performances of the op. 118 and 119 turned into an important milestone in classical music history: the first public performance of Brahms’s final works for piano.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter