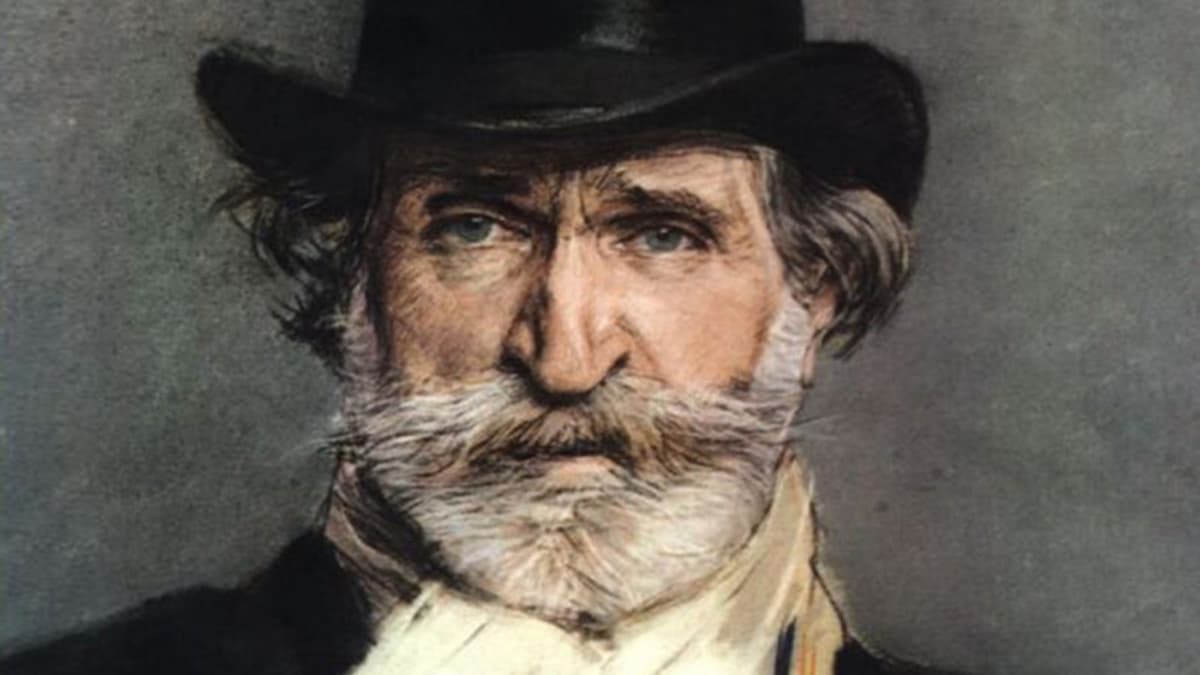

Giuseppe Verdi was born 10 October 1813 in Le Roncole, Italy.

Giuseppe Verdi © dallassymphony.org

Here are a few facts about his life to get you started:

- Verdi is most famous for his operas. Over the course of his six-decade-long career, he wrote twenty-eight operas, and astonishingly, about half of those can still be heard today at opera houses all around the world.

- Those operas played a significant role in the Italian nationalist movement of the nineteenth century. His works often touched on themes of independence and resonated with Italians pushing for national unification.

In fact, Verdi’s chorus of the Hebrew slaves, “Va, pensiero” from the opera “Nabucco“, became an unofficial anthem for the entire Italian unification movement, working to inspire a sense of national identity. - Verdi endured a series of horrifying losses as a young man. In 1838, his baby daughter died; in 1839, his baby son died; and in 1840, his young wife died, too.

These losses were the foundation on which his operatic career was built. Some suggest that his grief contributed to his ability to create convincing characters with tragic fates.

Perhaps in part because of the trauma of these early losses, he ultimately became an enigmatic, buttoned-up man who valued privacy, disliked biographers, and was generally difficult to know. - In the end, when assessing the art of Verdi, we have to rely more on his music for insight than anything he ever wrote or said himself.

With that history in mind, here are brief introductions to nine of Verdi’s most popular pieces of music, eight operas, and one stormy Requiem:

Nabucco (1841)

Later in life, Verdi described the brutality of his personal losses of 1838-40: “A third coffin goes out of my house. I was alone! Alone!”

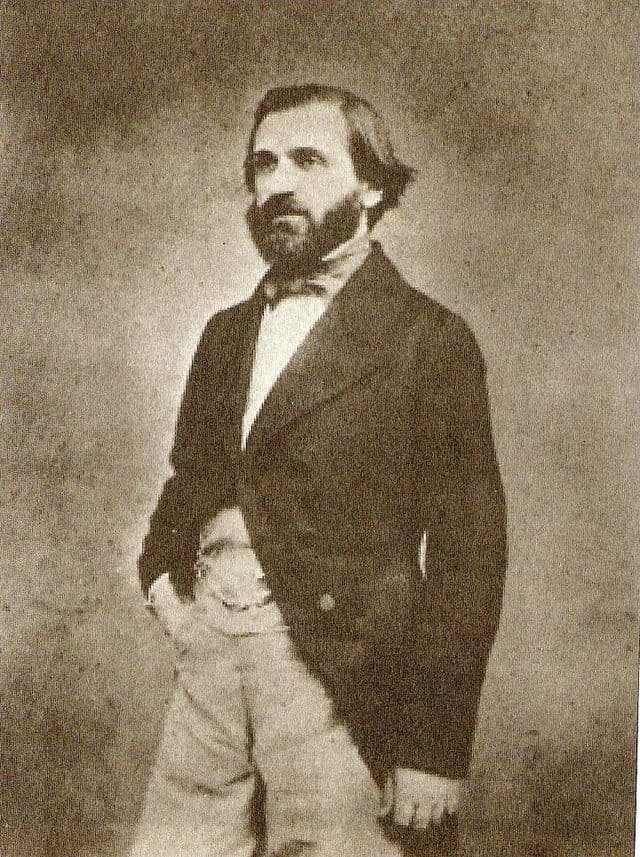

Giuseppe Verdi, 1844

Despite his grief, he composed. By the autumn of 1841, he finished the opera “Nabucco”, an opera based on the Old Testament story of King Nebuchadnezzar and the Israelites’ exile in Babylon.

Verdi said of it, “This is the opera with which my artistic career really begins. And though I had many difficulties to fight against, it is certain that Nabucco was born under a lucky star.”

As mentioned above, the most famous excerpt to come out of this opera was the chorus “Va, pensiero [sull’ali dorate]” (“Go, thoughts, on golden wings”).

It’s an encouragement for the oppressed Israelites to remember their homeland…a theme that clearly resonated with Italians of the era who were feeling oppressed by Austrian rule.

Rigoletto (1850-51)

Verdi spent the next decade in the musical trenches churning out operas.

His works from this era have not had the staying power that others did. However, the act of composing them was an invaluable education. They also set the stage for a legendary run of three masterpieces, which began with “Rigoletto.”

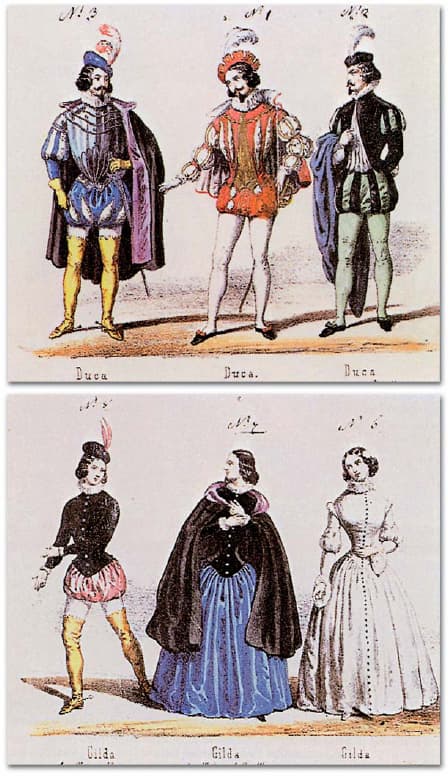

“Rigoletto” was based on Victor Hugo’s play “Le roi s’amuse” (“The King Amuses Himself”).

Characters include a womanizing Duke, a hunchback court jester named Rigoletto, and Rigoletto’s daughter Gilda.

Rigoletto: Costumes for the Duke and Gilda, 1851 (Ricordi)

Famously, Verdi knew he had a hit on his hands with the tenor aria “La donna è mobile” (“Woman is fickle”), sung by the slimy Duke. Verdi was so convinced it would be a hit and was so eager to safeguard against copycats that he forbade the tenor who was singing in the premiere from even so much as whistling the tune outside the opera house. It may have seemed extreme, but Verdi’s instincts were right: it became a blockbuster tune, and Verdi cashed in.

Il Trovatore (1851-53)

Early in the composition of “Il Trovatore”, Verdi was still preoccupied by “Rigoletto.”

After he finished “Rigoletto”, he was also working on his next opera, “La Traviata.” The wild productivity is enough to make one’s head spin.

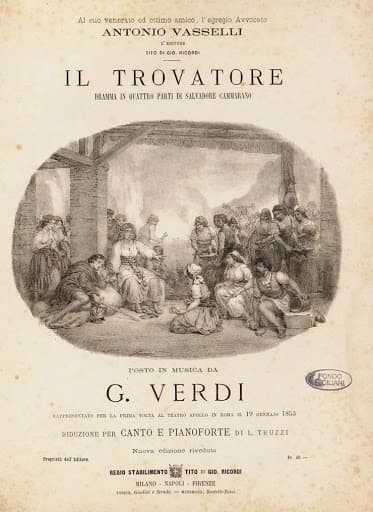

“Il Trovatore” premiered in January 1853.

Il Trovatore

The plot kicks off with a woman being burned at the stake for suspected witchcraft. In protest, the woman’s Romani daughter Azuceno tosses the executioner’s child into the flames.

Fast-forward years, and this dark, bloody, long-ago death ties the opera’s four main characters together.

- Count di Luna is the son of the executioner; his father has coached him all his life to avenge his sibling’s death.

- Azuceno, meanwhile, has raised a troubadour named Manrico as her son.

- Then, to top it all off, a noblewoman named Leonora is the love interest of both Manrico and the vengeful Count di Luna: a human symbol of their rivalry.

The big twist of the opera comes when it is revealed that Azuceno didn’t actually kill the Count’s brother in the flames. Rather, she killed her own child in a fit of confusion hearing her mother’s screams and then raised the baby originally meant for the bonfire – who turned out to be Manrico – as her replacement son.

In other words, Count di Luna’s quest for vengeance is for nothing, and the Count and Manrico are actually biological brothers.

The Count arrests Azuceno, captures Manrico, and condemns them to death. Leonora is in love with the troubadour Manrico and tries to bargain for his life by offering herself to the count, then she dies by suicide.

In a grim echo of the inciting action, Manrico is executed, too. Azuceno awakes from a sleep and reveals to the Count that he has killed his own brother.

There are several famous moments from this opera, but one of the best-known comes at the opening of the third act, when Verdi portrays the bustle of the Romani camp in the Anvil Chorus.

La traviata (1852-53)

In 1852, Verdi saw Alexander Dumas fils’s play “The Lady of the Camellias”, inspired by a true story of Dumas’s lover, the courtesan Marie Duplessis. Verdi soon set to work adapting it into an opera.

Marie Duplessis

The opera traces the story of a woman named Violetta, an independent courtesan known for her extravagant lifestyle. Despite the cynical outlook about men that she has had to cultivate to survive, Violetta falls deeply in love with Alfredo Germont, a young nobleman and poet.

Violetta decides to abandon her life as a courtesan and retire with Alfredo to the countryside. However, Alfredo’s father persuades Violetta to leave his son for the sake of his family’s reputation. Heartbroken, Violetta writes a breakup letter and returns to her former life in Paris. Alfredo follows her and more misunderstandings follow.

Violetta is terminally ill with consumption. However, in true operatic fashion, in the final act, just before she dies, Alfredo’s father reveals the truth behind their separation. The two ex-lovers are reunited right before Violetta’s death.

One of the most famous excerpts from the opera is a drinking song from a party scene called “Brindisi.”

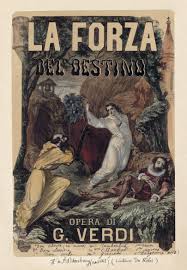

La forza del destino (1862)

“La forza del destino” (The Force of Destiny) premiered in 1862, and it remains one of Verdi’s most enigmatic and thrilling works.

In the opera, a Spanish marquis’s daughter named Leonora is about to elope with her Incan lover, Don Alvaro. She goes to leave the family home, but her father tries to stop her escape. In the scuffle, he is fatally shot. The lovers flee.

Leonora becomes separated from her lover. Alarmingly, she runs into her brother Carlo at an inn (fortunately, while she’s in disguise), and discovers that he wants to kill her. She begs the local Father Superior for protection, asking to live as a hermit in a cave in a life of penance. He shows her mercy and does so.

La Forza del Destino

In an operatic twist, Carlo and Alvaro end up serving in the military together and become best friends. Alvaro is injured in battle, but pulls through surgery. Unfortunately, Carlo breaks his friend’s trust and uses that time to snoop through his papers, discovering his identity. They fight but finally end things with Alvaro joining a monastery: a kind of metaphorical death.

Five years later, Carlo drops in at the monastery to see Alvaro, no longer able to contain his wish for vengeance. They duel near a cave, and Carlo is mortally wounded. Alvaro goes to the cave hermit and asks her to give absolution to his dying frenemy. Of course, the hermit is Leonora, and the former lovers recognize each other. She rushes to Carlo’s side to show him mercy. Just before he dies, Carlo kills his sister.

All of this drama is captured brilliantly in Verdi’s overture. It’s so appealing that it’s often used as a standalone orchestral showpiece.

Aida (1869-71)

When the Suez Canal opened in Egypt in November 1869, Isma’il Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, wanted Verdi to write a grand opera to celebrate. Verdi was nearing retirement and had no interest in the project…until he was offered 150,000 francs. He ended up accepting.

The opera is set in ancient Egypt and tells the story of Aida, a slave in Egypt who is secretly an Ethiopian princess. And as you can imagine, for maximum dramatic impact, Ethiopia and Egypt are at war.

Egyptian military commander Radames, oblivious to Aida’s origins, hopes to impress her with his military victories against Ethiopia. He does indeed win a victory against them, but unfortunately, troops have captured Aida’s father, the Ethiopian King.

To make things more complicated, the Egyptian king offers Radames his own daughter in marriage as a reward for his performance in battle. This is Radames’s chance to become heir to the Egyptian throne.

Aida’s captured father begs her to use her influence to get Radames to reveal troop locations, which she does. When Radames discovers what has happened, he orders father and daughter to escape, then turns himself into the Egyptian King for his traitorous actions.

Radames is sentenced to die by burial. The door is closed behind him in the vault, and he prepares to die there alone…until he sees that Aida has chosen to die with him, too.

One of the opera’s most famous moments is Radames’s triumphant return. Its glory and grandeur are heightened by the tragic end of the characters’ story.

Requiem (1869-1874)

Verdi’s Requiem, completed in 1874, is a monumental ninety-minute mass for the dead.

While not an opera, it still has been criticized as being too operatic for a sacred work.

It’s also unclear how much of the religious message the composer actually believed. His wife said in 1871, “I won’t say [Verdi] is an atheist, but he is not much of a believer.”

The requiem combines moments of soft, exquisite tenderness with outright thunder. A great performance is an awe-inspiring, emotionally charged, exhausting experience for both performers and audiences alike.

Otello (1884-87)

Verdi originally thought after the triumph of “Aida” in 1871 that “Aida” would be his last opera. Turns out he had two more in him, but he wrote them very quietly, so as not to have to deal with public pressure.

Press illustration of the 12 October 1894 Parisian premiere of the opera Otello by Verdi, performed by the Paris Opera at the Palais Garnier in a French translation by Arrigo Boito and Camille du Locle

The first of the two is based on Shakespeare’s tragedy Othello.

Otello, a Moorish general from Venice, returns to his home on the island of Cyprus after victory in battle. Trouble strikes when his ensign, Iago, starts a fight to frame Otello’s captain, Cassio. Otello, enraged, demotes Cassio. This is the first step in Iago’s plan to systematically destroy his boss.

Next, Iago tries convincing Otello that his young and very innocent wife Desdemona is cheating on him with Cassio. Desdemona inadvertently aggravates Otello’s suspicions by advocating for Cassio’s reinstatement. In one dramatic scene, Otello publicly insults Desdemona and throws her to the ground.

But his rage smolders, and he soon understands he has darker intentions. A puzzled Desdemona sings an Ave Maria before falling asleep. Otello sneaks into Desdemona’s room and strangles her for her “unfaithfulness.” When he finds out about Iago’s plot and Desdemona’s innocence, he is staggered. He dies by suicide in their bed.

Otello is considered to be one of Verdi’s crowning achievements, delving deep into complex psychological themes of jealousy, manipulation, and betrayal.

Here is the Ave Maria that Desdemona sings before her death:

Falstaff (1889-93)

Verdi’s final opera, “Falstaff,” premiered in 1893. Like “Otello,” it was inspired by Shakespeare and stands as a delightful, comedic contrast to that tragedy.

Falstaff is a portly knight with money trouble who attempts to woo two wealthy women named Alice and Meg simultaneously. He sends them duplicate love letters, and they meet up and laugh over them.

Falstaff visits Alice’s home and attempts to seduce her, but Meg interrupts. Alice’s husband is furious and on his way; he believes that Alice really loves Falstaff. Falstaff panics and hides in a laundry basket. Alice then tells her servants to toss the contents of the basket into the Thames.

Falstaff is undeterred. Alice asks Falstaff in a letter to dress in costume as a character known as the Black Huntsman, and to meet her in the park at midnight. She also hires mutual acquaintances to dress up as characters like the Queen of the Fairies. Falstaff is poked and prodded by them and agrees to give up the chase. To end the opera, two sets of supporting characters are married.

Conclusion

We wrote an article about Verdi’s death.

Verdi was one of the most celebrated and prolific composers of the 19th century. His operas, ranging from historical epics to intimate tragedies, continue to resonate with people all around the world.

Verdi may have been a difficult man to get to know, but his operas paint a portrait of a great creative mind that was simply unrivaled in nineteenth-century Italian opera.

For more on Verdi, visit our tag.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter