There comes a moment in a musician and composer’s life, where the question of teaching music is asked. Particularly when it comes to teaching their own children, and transmitting both the passion and the knowledge gained over the years to the generations to come. Some of the most well-known composers were also excellent teachers — Vivaldi, Haydn, Orff or Messiaen, for instance —, and have left many manuals and textbooks used until today. Some have even composed with the intention of teaching — Bach, Schumann and Bartók are some of the most memorable composers who have a body of work that is both intended for performance and for musical development. One of the most famous works for keyboard — and today piano —, The Well-Tempered Clavier was devised in a manner in which the performer would develop technique on the instrument, as well as learn repertoire pieces.

Béla Bartók

In fact, some composers have devised methods of their own. Such as Bartók and his Mikrokosmos, a catalogue of works for piano which was intended to teach the instrument to his own children, in a truly unique way. It is still to this day one of the most interesting teaching methods, as well as a collection of piano pieces for performance. Mikrokosmos teaches from the perspective of Bartok’s cultural background, and brings children to discover rhythms, melodies and harmonies less heard.

Bartók: Mikrokosmos

Shinichi Suzuki with young violinists, Wembley 1980 © spectator.co.uk

Music pedagogy cannot be discussed without mentioning the Suzuki method, developed by Japanese violinist and pedagogue Shinichi Suzuki, one of the most well-known modern teaching methods. It has been used in many countries around the world, and has been adapted and translated into many languages too. It was initially developed for violin, and then expanded to viola, cello, piano, bass, flute, recorder, guitar, harp, voice and organ. It is such a successful music curriculum that it can be applied to almost any instrument. Today it is one of the most famous musical guides for both professional and amateur development, and Suzuki is regarded as one of the most prolific musical educators.

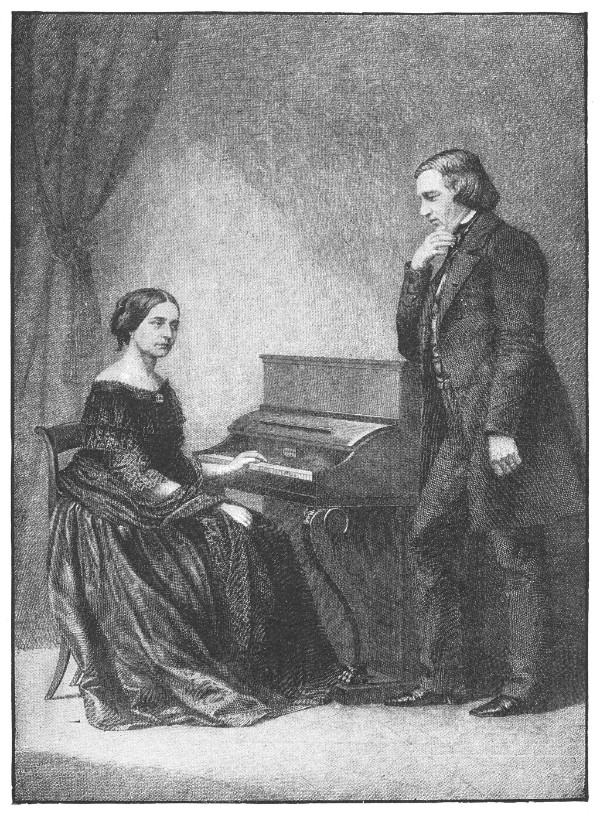

Johann Sebastian Bach playing the organ, c. 1881

One cannot look at the body of work of Bach without also highlighting how didactic his work was. His entire life has been focused on teaching, whether his students or even his family. From the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach — both a collection of musical works and a method to develop technique — to the Well-Tempered Clavier, as mentioned previously — a work designated to improve musical technique through the forms of the fugue and the prelude —, many of his works carry the intention of teaching. It is no surprise that he is today considered as one of the founding fathers of Western classical music, having laid down many of the composing and performing rules still used today.

Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach – Complete Minuets

© classful.com

What matters the most in teaching music, perhaps, is the transmission of the passion for it. In the end, it matters less how the student approaches the practice and more how the fire is ignited. If one is able to teach music, then it is great, but if one is not, then this should not discourage eager musician parents from enrolling their children in music programmes. There really is no right or wrong in teaching music, despite what rumours say. It does not have to be what may seem as stuffy and rigorous conservatory curriculum, and nowadays the options are plenty; from concert hall introduction days, to music activities, classes one-to-one lessons; there is an opportunity for each budget, and this is not to mention online options! In the end, there are no negative impacts to music, and forming a life with it will only benefit the child and future adult. So whether it is for pleasure or with the aim of professional development, it is important that all children get introduced to music as quickly as possible!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter