This year, 2024, is the one-hundredth anniversary of the death of Italian composer Giacomo Puccini in November of 1924. Known for his brilliant and spectacularly admired operas, he was virtually the Taylor Swift of his era. My husband and I were thrilled to hear Tosca this week live in HD from the Metropolitan Opera. The dramatic opera in three acts, written near the end of Puccini’s life, was first performed in 1900 in Rome and features instruments that one would not necessarily associate with an opera house—instruments that are crucial to enhance the story of passion, violence, political corruption, and deceit.

2024 production of Tosca © The Metropolitan Opera

We were treated to the divine soprano Lise Davidsen as Tosca; tenor Freddie De Tommaso in his MET debut as Cavaradossi, Quinn Kelsey as the menacing Scarpia, with the brilliant conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Listen to the heartbreak in the Act II aria Vissi d’arte Lise Davidsen sings during her MET role debut performance.

Tosca: “Vissi d’arte”

Expressive and tumultuous, the score is driven ever forward and continuously increases in tension. Tosca is written in the verismo or “true” Italian post-Romantic operatic style known for realistic depictions of everyday life and depicting the struggles that plague us all. Puccini introduces known settings in Rome with some spoken dialogue, depiction of the thoughts of the characters, and sounds within the drama that the cast also hears, such as church bells and two cannons.

Lise Davidsen © Fredrik Arff

The first act is gripping, and three unusual instruments enhance the dynamic story, especially in the Te Deum at the end of the first act. The setting is in a church filled with worshippers, but meanwhile, inmates have escaped from a nearby prison, and a cannon signals the escape. Puccini assembles massive forces— the soloists, the orchestra, the chorus, a pipe organ, a huge bass drum, and giant chimes from their perch backstage, not to forget the cymbals, brass, and the final moments sung and played in unison. A recording of these sound effects just isn’t adequate for the MET. Listen for yourself as Scarpia, singing above the huge forces, reveals his evil intentions. “Tosca, you make me forget God.”

Tosca: Te Deum

Did you know that the MET has an enormous 15-foot-tall pipe organ backstage that thunderously enters at this point in the opera? The Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ, originally installed in 1965, was in desperate need of restoration. One of the Opera’s organists, Dan Saunders, summed up what had to be done this way, (from an article from Diapason by Craig R. Whitney) “We played it to death—it needed to be brought back to life.” The two main reservoirs were in danger of failing at any moment. And the organ’s unpredictability was not the only issue. Buried deep in the wings stage left, the organist could neither see the conductor from the console nor hear themselves well. The musician needed to play ahead of the beat to stay with the orchestra. Not until a visual and an audio monitor was installed could he or she hear and see.

Thanks to funding from MET supporter Frederick R. Haas, through his family’s Wyncote Foundation, the distinctive instrument with two manuals and 1,289 pipes was whisked away from Lincoln Center to Ohio. Taken apart piece by piece and shipped to and fro on a flatbed truck, it took quite a team to put it back together, especially the 16-foot pedal bass pipes.

Originally intended to be moveable and on wheels, the nine-ton organ is much too heavy for the stage. It’s in its permanent spot backstage. Adding to the weight is a chamber that encloses the entire organ, seventeen feet wide, by seventeen feet high, and nine feet deep. Protective steel bars have been installed on the back and side walls of the organ, and the roof has been reinforced to ensure the organ is protected from intense activity backstage. Flying objects might damage the instrument. The electrical systems were updated too, and then another team came in to tune and voice the organ. With a cable connecting the organ console and the instrument, the organist can now sit in the orchestra pit with his or her colleagues and can coordinate with the conductor.

On October 4, during the 2022-2023 season, the organ made its MET debut just in time for Tosca, shaking the very rafters and resonating in the enormous opera house. The organ was also featured during that season in Britten’s Peter Grimes, and Wagner’s Lohengrin.

Giacomo Puccini: Tosca – Act I: Tre sbirri, una carrozza (Tito Gobbi, baritone; Angelo Mercuriali, tenor; Milan La Scala Chorus; Milan La Scala Orchestra; Victor De Sabata, cond.)

But the sound of the organ was not enough for Puccini. He called for a cannon to sound. To emulate the boom, a bass drum with cataclysmic volume was necessary. The industrious team led by the MET’s head of music, Thomas Lausmann, searched the world and found Bass Drum XXL produced by a company in Germany. The enormous instrument is also installed backstage. The musician who strikes it must mount a ladder to play it, and the percussionist and anyone around needs hearing protection. Everything vibrates!

The bass drum is featured in several operas in addition to Tosca, including Verdi’s Nabucco and his Requiem, another work with stunning intensity and volume.

In fact, New York Times correspondent Oussama Zahr wrote a review in September of 2023 of Verdi Requiem and put it this way, “Credit, too, to the percussionist Gregory Zuber, who walloped his bass drum with such fantastic force that he was momentarily airborne.”

Verdi’s Requiem: “Dies irae”

The third instrument that Puccini mandated are the chimes. You’ve perhaps seen chimes, a carillon-like instrument with up to 22 suspended and pitched bells, in an orchestra on a moveable stand.

Tubular bells

The MET’s super-sized chimes, the largest of which is 15 feet long and weighs 500 pounds, the size and length necessary to get the right pitch, had to be transported from Houston, Texas on a flatbed truck. Mounting them was quite the challenge as the colossal chimes were unwieldy to handle, to say the least.

As if that spectacle isn’t enough, the third act features the brilliant 50-voice children’s chorus and introduced by dazzling French horns, a shepherd boy sings a plaintive solo offstage at the beginning of Act III accompanied by ringing church bells.

Giacomo Puccini: Tosca – Act III: Io de sospiri (Eva Marton, soprano; José Carreras, tenor; Juan Pons, baritone; István Gáti, bass; Italo Tajo, bass; Ferenc Gerdesits, tenor; József Németh, bass; Jozsef Gregor, bass; Benedek Heja, boy soprano; Hungarian Radio and Television Chorus; Hungarian State Opera Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

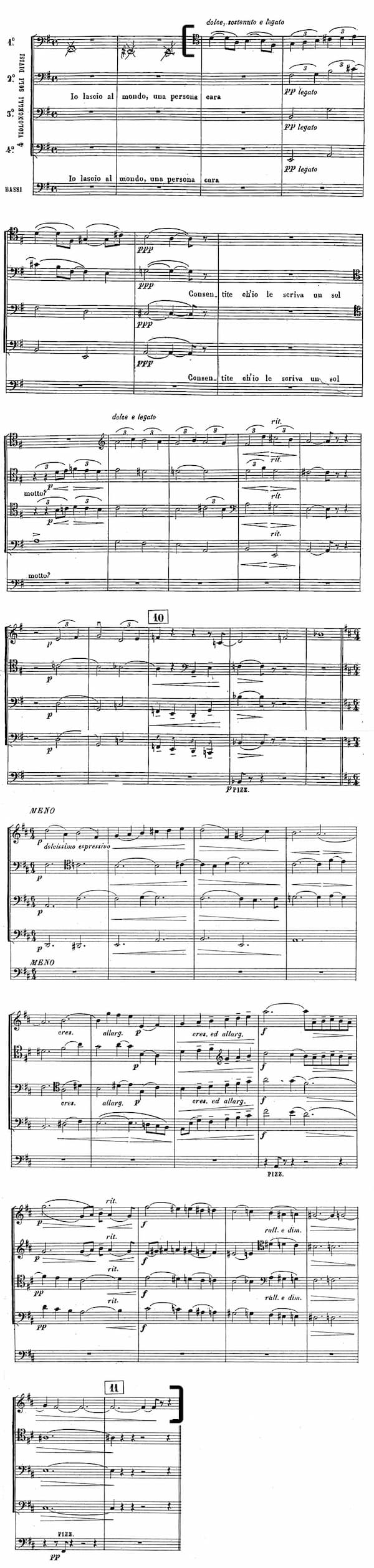

Since I’m a cellist I’m eager to hear the famous and extended cello solo quartet, four cello players, in Act III of Tosca. What could be better to depict the tragic scene before the execution? It’s lyrical and heartrending, the lead was beautifully played by Rafael Figueroa. Because the first part goes quite high, almost off the fingerboard, this excerpt is often requested for cello auditions.

Cello excerpt from Puccini’s Tosca

Giacomo Puccini: Tosca – Act III: Mario Cavaradossi? (Eva Marton, soprano; José Carreras, tenor; Juan Pons, baritone; István Gáti, bass; Italo Tajo, bass; Ferenc Gerdesits, tenor; József Németh, bass; Jozsef Gregor, bass; Benedek Heja, boy soprano; Hungarian Radio and Television Chorus; Hungarian State Opera Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond.)

Several operas do have solos for the first cello and the concertmaster, but usually, the musicians are acknowledged when they stand for a bow in the pit below the stage lip. Recognizing their artistry, especially the lengthy solos in the MET’s premier of the Richard Strauss opera Die Frau Ohne Schatten last month—it’s really a solo cadenza for the cellist—Yannick in a wonderful gesture, invited concertmaster David Chan and principal cello Rafael Figueroa to join the cast onstage for a solo bow.

Richard Strauss: Die Frau ohne Schatten, Op. 65, TrV 234 – Act II: Verwandlung (Vienna State Opera Orchestra; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

Rafael Figueroa, Yannick Nézet-Séguin and David Chan v

Imagine the sound of that size of stage, mirrored by the equally massive backstage, the power of the orchestra, and the hall itself, which can accommodate 3,732 audience members. Surprising, and what an experience.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter