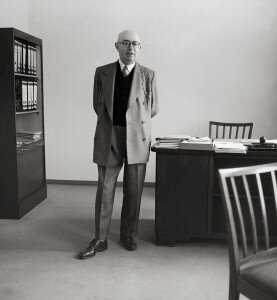

Some consider him one of the most important philosophers and social critics in Germany after World War II, while others declare him to be “preposterously over-rated.” Whatever the case may be, Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno (1903-1969) was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical theory, who passed away 50 years ago, on 6 August 1969. He certainly was a highly versatile personality who wrote copiously on music, philosophical and sociological tropics including scathing critiques of contemporary Western society. Adorno was the only son of a wealthy German wine merchant of assimilated Jewish background and an accomplished musician of Corsican Catholic descent. For several decades Adorno regarded his creative musical work as the core of his thought processes, and he wrote to Alban Berg in 1925 asking to be accepted as a composition student. “Perhaps you remember me,“ he writes. “I was born in Frankfurt in 1903, completed my secondary education there in 1921, and earned my doctor of philosophy degree at the University of Frankfurt in 1924 with an epistemological study. I have been interested in music since my childhood; I first played the violin and then the piano. I also made my first attempts at composition at an early age. I taught myself harmony and went to Bernhard Sekles with songs and chamber music in 1919. Since then I have been his student.”

Some consider him one of the most important philosophers and social critics in Germany after World War II, while others declare him to be “preposterously over-rated.” Whatever the case may be, Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno (1903-1969) was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical theory, who passed away 50 years ago, on 6 August 1969. He certainly was a highly versatile personality who wrote copiously on music, philosophical and sociological tropics including scathing critiques of contemporary Western society. Adorno was the only son of a wealthy German wine merchant of assimilated Jewish background and an accomplished musician of Corsican Catholic descent. For several decades Adorno regarded his creative musical work as the core of his thought processes, and he wrote to Alban Berg in 1925 asking to be accepted as a composition student. “Perhaps you remember me,“ he writes. “I was born in Frankfurt in 1903, completed my secondary education there in 1921, and earned my doctor of philosophy degree at the University of Frankfurt in 1924 with an epistemological study. I have been interested in music since my childhood; I first played the violin and then the piano. I also made my first attempts at composition at an early age. I taught myself harmony and went to Bernhard Sekles with songs and chamber music in 1919. Since then I have been his student.”

Theodor W. Adorno: 6 Studies for String Quartet

Adorno was a classically trained pianist who held great sympathies for the twelve-tone technique of Arnold Schoenberg in opposition to Igor Stravinsky. Adorno favored the radical liberation of the musical material, and harshly criticized Stravinsky for withdrawing from this freedom and taking refuge in the forms of the past. His exclusive championing of the Second Viennese School even roiled Schoenberg, who wrote, “I have never been able to bear the fellow… It is disgusting, by the way, how he treats Stravinsky.” However, Adorno’s commitment to avant-garde music would form the backdrop of much of his subsequent writings, and even led to his collaboration with Thomas Mann on the novel Doctor Faustus. Adorno had been forced to leave Germany, and from the spring of 1934 he made his residence in Oxford, New York City, and southern California. A good number of books for which he later became famous were written in exile, including the Dialectic of Enlightenment, Philosophy of New Music, The Authoritarian Personality, and Minima Moralia. As a critic of both fascism and what he called the “culture industry,” his writings strongly influenced the European New Left.

Adorno was a classically trained pianist who held great sympathies for the twelve-tone technique of Arnold Schoenberg in opposition to Igor Stravinsky. Adorno favored the radical liberation of the musical material, and harshly criticized Stravinsky for withdrawing from this freedom and taking refuge in the forms of the past. His exclusive championing of the Second Viennese School even roiled Schoenberg, who wrote, “I have never been able to bear the fellow… It is disgusting, by the way, how he treats Stravinsky.” However, Adorno’s commitment to avant-garde music would form the backdrop of much of his subsequent writings, and even led to his collaboration with Thomas Mann on the novel Doctor Faustus. Adorno had been forced to leave Germany, and from the spring of 1934 he made his residence in Oxford, New York City, and southern California. A good number of books for which he later became famous were written in exile, including the Dialectic of Enlightenment, Philosophy of New Music, The Authoritarian Personality, and Minima Moralia. As a critic of both fascism and what he called the “culture industry,” his writings strongly influenced the European New Left.

Adorno was highly critical of jazz and popular music, essentially viewing both as part of the prevailing culture industry. He saw the culture industry “as an arena in which critical tendencies were eliminated, as it produced and circulated cultural commodities through the mass media manipulating the population. With easy pleasures available through consumption of popular culture, people became docile and content, no matter how terrible their economic circumstances.” Adorno saw the objective realities of the production of mass culture as a form of reverse psychology, and not as moral degeneracy ascribed to sexual and racial influences. A good number of his followers believe that today’s society has evolved in the direction foreseen by Adorno, while his theories are highly contested in terms of current cultural studies and thoughts. The English philosopher Roger Scruton wrote, “Adorno had produced reams of turgid nonsense devoted to showing that the American people are just as alienated as Marxism requires them to be, and that their cheerful life-affirming music is a ‘fetishized’ commodity, expressive of their deep spiritual enslavement to the capitalist machine.”

Theodor W. Adorno: 6 Kurze Orchesterstücke, Op. 4

Theodor W. Adorno: 6 Kurze Orchesterstücke, Op. 4

Adorno returned to Frankfurt in 1949 and became a member of the philosophy department. He quickly became an important figure in the “Institute of Social Research,” an intellectual hub that subsequently became known as the Frankfurt School. He took on the directorship in 1958 and became a leading figure in the “positivism dispute” in German sociology. He advocated a complete restructuring of German universities, and right-wing critics mercilessly hounded him. Undeterred, he continued to publish profusely on authoritarianism, anti-Semitism and propaganda, and he died of a heart attack, one month shy of his sixty-sixth birthday. Whether you subscribe to his theories or not, Adorno “remains the single most influential contributor to the development of qualitative musical sociology.” And with a good number of his twenty-seven essays on music only recently published in English translations, his aesthetic reflections will undoubtedly spawn further critical discourse and debate.