Lauded by Gramophone as ‘among the most recorded of contemporary composers in the UK’, the music of British/French/Israeli composer Nimrod Borenstein is being increasingly performed on the international stage, with performances of his music from London’s Royal Opera House to Hong Kong’s City Hall, as well as around Europe, Australia, Israel, the Americas, and Asia.

Clélia Iruzun plays Nimrod Borenstein’s Barcarolle

In the UK Nimrod has worked with orchestras including the Royal Philharmonic and Oxford Philharmonic, the latter of which spearheaded a recording of his Violin Concerto along with two other symphonic works, The Big Bang and Creation of the Universe and If You Will It, It Is No Dream, with Vladimir Ashkenazy at the helm.

Nimrod’s music feels highly melodically driven, with kaleidoscopically colourful orchestration and subtle yet surprising harmonies. His discography to date captures a large variety of his prolific output: we see his larger symphonic works and concertos for violin and piano next to more intimate pieces such as Quasi una cadenza, a solo violin piece that has been recorded by three separate violinists.

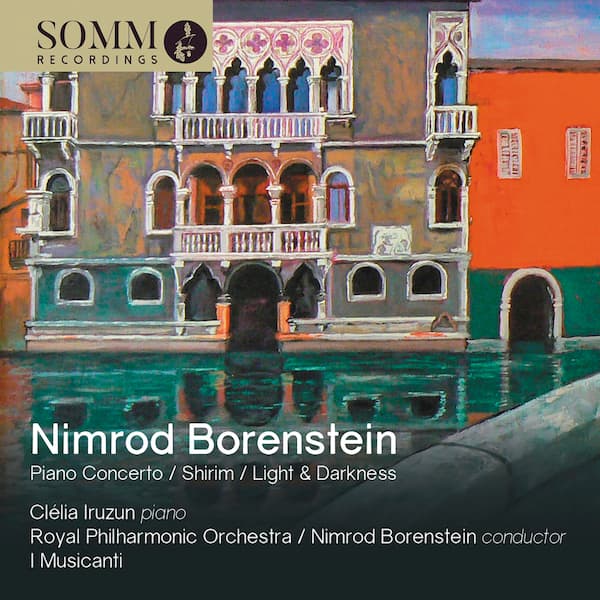

Borenstein/Iruzun/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra SOMM Album

‘That’s unusual for a living composer, as far as I know,’ says Nimrod, ‘to have the same work recorded several times. I think that it goes with my type of career that has come from the bottom up, not from the top down.’

Nimrod Borenstein © Synced Films

As a violinist-turned-conductor who nowadays frequently conducts his own pieces, Nimrod has always valued the collaborative aspect of making music. ‘Most of my career has been made through performers, not organisations,’ he states. ‘Several concertos were commissioned by the performers themselves, and there is a special feeling when you know the performers chose your music not because it was paid for by a festival or something, but because they really love it. It’s how it should always be, and it also means that when you’re on stage together, there is a nice feeling.’

Pianist Clelia Iruzun is the soloist in the most recent album of Nimrod’s music, a recording of his Piano Concerto made with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in 2023. Nimrod conducted the recording sessions, reflecting his passion to collaborate as closely as possible with other performers. Musing on the legacy left by conducting one’s own works, Nimrod says ‘If you know totally what you want from every single note, and you also spent 500 hours composing the work, you will know it like no-one else. If we could have recordings of Brahms conducting his symphonies, or Beethoven, or Mahler, that would be interesting, so I think that leaving this kind of recording of my orchestral music is an exciting thing for me as a conductor.’

Does Nimrod manage to keep his composer and conductor hats separate once the music is on the performers’ stands? ‘For me, the piece is really finished when I finish writing it,’ he says.

‘I did a concert recently with the ECO [English Chamber Orchestra] where I conducted Elgar and my music, and there was no difference for me whether I conducted Elgar or my work. It’s music. When the work is finished, it’s almost as if I didn’t write it myself.’

Edward Elgar: Chanson de Matin (arr. Borenstein)

The ECO will feature on an upcoming recording to be made this July, again featuring Nimrod as both composer and conductor. The disc will feature three works for soloist and orchestra: his Shakespeare Songs for soprano and orchestra featuring Sarah Fox, an oboe concerto with Sanja Romic, and a new Mandolin Concerto with rising star mandolinist Alon Sariel.

The three pieces were written at the end of an almost ten-year period during which Nimrod composed over 10 concertos, including for viola, bassoon, harp, and saxophone. The three featured works on the ECO album sit almost as neighbours chronologically – the opus numbers are 97, 99, and 101 – and mark an informal end to his deep dive into the world of the concerto.

Despite the format of ‘soloist-plus-orchestra’ being fixed, Nimrod still believes there is plenty of space for invention and variety.

‘When we hear three notes of Beethoven or Schumann we know who it is, even if we don’t know the piece,’ says Nimrod. ‘It means that actually there is something that is very similar in whatever they write, and you cannot escape that.

For the concertos, I was conscious of that. With this CD, apart from the advantage of the mandolin being very different from the oboe, I also attempted different forms inside the pieces.’

As well as being able to leave a legacy of his music, Nimrod looks for the surprises that occur in recording sessions, the moments between the notes themselves.

‘Recording is a great advantage of the modern age, as a composer,’ he says. ‘As a composer, I will want people to have an idea of how I want my music to be played, but notation is sometimes limited. Certain things seem to be obvious, but they’re not. The most important things seem not to be obvious, and you can somehow leave a testimony of that in your recordings.’

But above all of that? Recording is about capturing the spontaneity of the moment. ‘I like to do recordings as if they were concerts, so you do long takes’ says Nimrod. ‘It’s the magic of the music that counts.’

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter