“As time goes on most of my works will be more and more neglected”

Max Bruch

Max Bruch (1838-1929) is almost exclusively associated with his famed G-minor violin concerto. However, throughout his long and industrious musical career he composed well over 200 works that are thoroughly grounded in a conservative German romantic tradition. All exhibit a clear sense of structure and a reliance on melodic processes.

Max Bruch: String Quartet No. 1 in C minor, Op. 9 (Mannheim String Quartet)

Early Compositions

Bruch’s The Swedish Dances

His First Published and Unpublished Symphonies

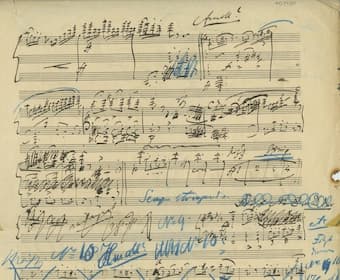

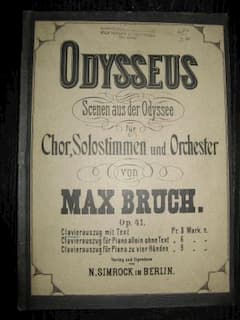

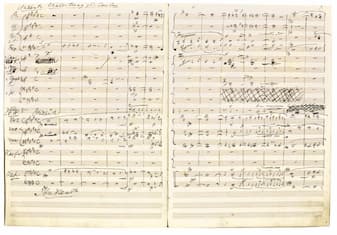

Max Bruch’s Oratorio Odysseus

Bruch went public with his first symphony in March 1852. A critic for the Rheinische Musikzeitung compared Bruch to Mozart and Mendelssohn. He further writes, “May he courageously step forward on the path he has begun, serve art as the noble holy goddess only for its own sake and find his goal only in the attainment of the highest and best! With all our hearts we wish him the best of heaven’s blessings!” That particular symphonic juvenilia remained unpublished, and it was only with the encouragement of the conductor Herrmann Levi that Bruch turned his attention to the composition of his first published symphony.

Bruch’s Overture to Loreley

Max Bruch: Symphony No. 3 in E Major, Op. 51 (London Symphony Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Massive Works for Choir and Orchestra

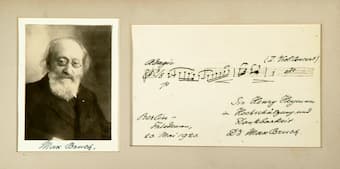

Bruch’s gift for Henry Heyman 1920

Bruch was an unusually ambitious and productive composer, and his greatest successes in his own lifetime were massive works for choir and orchestra. His male-voice cantata “Fithjof” (1864), the “Beautiful Ellen” (1867) and “Odysseus” (1872) were favorites with German choral societies during the late 19th century. Bruch demonstrated an extraordinary power and facility in the manipulation of large vocal forces, and his choral writing is the work of a completely accomplished musician. Although these works are spontaneous, tuneful and effective, they failed to remain in the repertoire for a variety of reasons. Amateur music making in Germany was being stimulated by the industrial revolution, and a great number of orchestras and choral societies were affiliated with factories. As a composer, Bruch was torn between accepting official employment wherever one might become vacant, and the advantages and disadvantages of being a freelance artist. As such, his choral compositions became musical calling cards to support one or the other career path.

Max Bruch: 9 Lieder, Op. 60 (Darmstadt Concert Choir; Wolfgang Seeliger, cond.)

His Tenure as Music Director of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society

Plague of Max Bruch in Liverpool

Between 1880 and 1883, Bruch was appointed Music Director to the Liverpool Philharmonic Society. He was responsible for conducting bi-weekly concerts between October and March, and worked with the amateur chorus and the freelance orchestra. Liverpool was considered the gateway to America, and the city was home to a large continental population, particularly Germans. The German immigrant Andrew Kurtz was a lover of music, a member of the Philharmonic Society and an amateur pianist who invited friends to his home to play chamber music. He was head of a chemical factory, and part of Bruch’s Liverpool circle of friends. Bruch started composition on a Piano Quintet for Kurtz in 1881, but the work was still incomplete in 1886. Kurtz pleaded with Bruch in January 1886, “We are all anxious for the completion of the work, which of course we rarely play because of its incompleteness, and because we have been anticipating every week to receive the conclusion of the last movement.” Bruch eventually did complete the work, and it carried the dedication in English, “composed for and dedicated to Mr. A.G. Kurtz in Liverpool, Breslau 1886.” Bruch provided his own historical assessment in conversation with the American music critic Arthur Abell in 1907. “As time goes on, Brahms will be more appreciated, while most of my works will be more and more neglected. Fifty years hence he will loom up as one of the supremely great composers of all time, while I will be remembered chiefly for having written my G-minor Violin Concerto.”

Franz von Suppé.

Dear Mr Predota,

I have taken great interest in your comments. I am the manager of Sterling Records, in Stockholm, Sweden.

My personal interest is just the same as you, the romantic orchestral music.

I wonder if you may be able to solve a mystery.

We understand that Suppé wrote a symphony. Do you happen to know the whereabouts of this work…

We would love to do a recording,

we look a lot forward to your information, thanking you in advance,

all the best

Bo Hyttner

Sterling Records, Stockholm, Sweden

Dear Mr. Hyttner,

Many thanks for contacting Interlude.

Unfortunately Mr. Predota doesn’t have any information on that particular work, but you might want to try the following site:

http://operetta-research-center.org/tag/franz-von-suppe/

With best wishes

Juliette