John Keats

The English Romantic poet John Keats (1795-1821) tragically died from tuberculosis at the age of 25. Creating a profound body of work under the cloud of near-constant illness, Keats captured extreme emotions through an emphasis on natural imagery. In the series of odes he contemplates mortality, nature, time, and art’s role in making these abstractions real and personal. Critics praised him for having “developed a style which was more heavily loaded with sensualities, more gorgeous in its effects, more voluptuously alive than any poet who had come before him.” The richness and depth of his verse appears to resist music, and Keats is therefore not the most frequently Romantic poet set to music. But that does not mean that composers have not been drawn into his poetic word. The Scottish composer and educator John Blackwood McEwen (1868-1948), was inspired to compose three instrumental preludes on three lines from the Keats Epistles.

John Blackwood McEwen: 3 Keats Preludes (Geoffrey Tozer, piano)

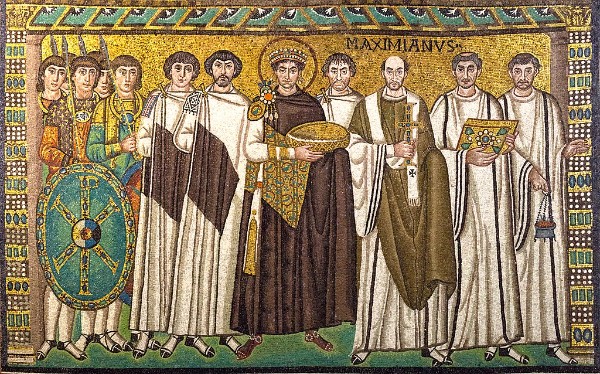

Part of several “Great Odes of 1819,” Ode on a Grecian Urn is a complex and mysterious poem. An undefined speaker looks at a Grecian urn, which is decorated with evocative images of rustic and rural life in ancient Greece. These scenes fascinate, mystify, and excite the speaker in equal measure—they seem to have captured life in its fullness, yet are frozen in time. The speaker’s response shifts through different moods, and ultimately the urn provokes more questions than it can answers.

John Blackwood McEwen

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

Clarinetist and composer Mark G. Simon set four of the five stanzas of Keats’ ode, noting that the “poem’s very existence to the power of art deeply affects people’s lives.”

Mark G. Simon: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Op. 24 (Linda Larson, soprano; Mark G. Simon, clarinet; Aleeza Meir, piano)

The final stanza of Keats’ poem has remained the subject of varied interpretations. The urn seems to tell the speaker—and, in turn, the reader—that truth and beauty are one and the same.

Ode on a Grecian Urn

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Gustav Holst

The notion that classical Greek art was idealistic and captured Greek virtues, resonated deeply with Gustav Holst (1874-1934). When he was commissioned by the 1925 Leeds Triennial Festival to write a new work for the event, the composer turned to poetry by John Keats. Instead of setting complete poems, he selected various unrelated passages that stimulated his musical imagination. In the end the work became a four-movement choral symphony, with the second movement becoming a setting of the Ode on a Grecian Urn.

Gustav Holst: First Choral Symphony, Op. 41 (Felicity Palmer, alto; London Philharmonic Choir; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Adrian Boult, cond.)

In his Ode to a Nightingale, John Keats traces a journey through a landscape where nature, death, and life pass in a mysterious dream. First published in 1819, the poem explores two primary issues. First is the connection between agony and joy, and second is the connection between life and death. The poet artistically draws a comparison between the natural and the imaginative world as represented by a nightingale. He tries to seek comfort and harmony in his imaginative world, but the pull of his consciousness brings him back to confront the heart-wrenching realities of life. Ultimately, he realizes that only death can offer a permanent escape from pain.

Ode to a Nightingale

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

Andre Earle Simpson: Birds of Love and Prey – No. 4 Night Interlude (Deborah Sternberg, soprano; Andrew Earle Simpson, piano)