Maurice Ravel only wrote two piano concertos, and they are so individual in sound that they stand for a whole lot more. The first was the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, M. 82, written on commission for one-handed pianist Paul Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein, who had a promising career cut short by loss of his right arm in WWI, created his own repertoire by commissioning the leading composers of the day, including Hindemith, Richard Strauss, Korngold, Britten, and Ravel, among many others, to write original works for him. He also made his own arrangements of music that had been in his repertoire before the war, when he was a touring soloist.

Maurice Ravel

Paul Wittgenstein

As the commissioner, Wittgenstein regarded the works as his and they could only be played if he was hired as the soloist. He also felt free to make changes as he saw fit, since he owned the work, and this often led to confrontations with the composers. He and Ravel famously disagreed about the extended piano solo that followed the orchestral introduction, but Ravel refused to change the work to include the orchestra at that point. Wittgenstein gave in and gave the premiere of the work in Vienna on 5 January 1932 with Robert Heger conducting the Vienna Symphony Orchestra.

Like other Ravel works, the first movement seems to come from nowhere. It opens in a dark Lento, not unlike what was heard in 1912 in Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloé. The orchestra builds to a climax and the piano emerges alone. Ravel’s writing is such that you would be hard pressed to say if it was actually played only by the left hand.

Maurice Ravel: Piano Concerto for the Left Hand – I. Lento

For a normally two-handed pianist, this entrance is difficult to do satisfactorily. For a one-handed pianist, it’s an immediate statement on the virtuosity inherent in only one hand.

The whole concerto is written in one movement, divided into three sections. After the opening Lento section and the piano’s entrance, an abrupt shift to a 6/8 Allegro follows, described as either ‘a determined march or a furious scherzo’. Ravel regarded this section as improvisatory in nature, akin to a jazz movement made up of the themes of the first section. After the climax, the first Lento section returns, concluded by a virtuosic cadenza.

The second piano concerto, written for two hands in G major, was intended to be a contrast with the heaviness and overstatement that filled so many 19th-century concertos. Ravel wrote a work for piano and orchestra, not piano versus orchestra. His original intention was to call the work Divertissement, but, in the end, the title Concerto conveyed what he wanted.

The most distinctive element in the work is Ravel’s insertion of jazz lines, blues notes, and a lyrical E major theme that sounds very much like part of Gershwin’s earlier Rhapsody in Blue. Ravel even includes sections in the second theme, in an extended solo cadenza, that should sound like the musical saw.

What seems light and improvised in the second movement was hard work for Ravel. He was writing in multiple metres at once: a 6/8 accompaniment against a 3/4 melody creates its own tension – expected strong beats aren’t emphasised and phrases seem to move across bar lines, suspending the listener outside of time. The final movement pits the piano against the first chairs in the orchestra, with everyone coming out with something to say. The movement and the piece end as it starts, with percussive chords.

Although he intended to be the soloist for the premiere, ill-health prevented this and he left the premiere to pianist Marguerite Long, while he conducted the orchestra. The debut on 14 January 1932, the same month as the Wittgenstein premiere, was successful, and they toured and recorded the work, although Pedro de Freitas Branco took over the conducting duties for the recording, under Ravel’s supervision.

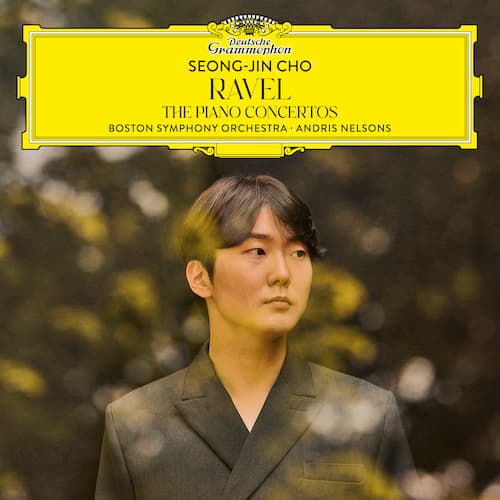

Seong-Jin Cho (photo by Ben Wolf)

Seong-Jin Cho rises to the occasion, first with one hand and then with both. Ravel’s writing shows so many influences, from American jazz, Russian colouring and modes, and all the musical changes happening in France in the early 20th century that it’s difficult to characterise his work as being other than international.

The difficulties in walking into a work as complex as the Concerto for the Left Hand are more than just playing with one hand. This work was refined by the master of the left hand – he knew his capabilities – and for the pianist who takes this on, confining one’s art to only one hand is more difficult than it sounds. Seong-Jin Cho can convince us on the audio. If you need to see the video, there’s a glimpse here.

Seong-Jin Cho performs Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the left hand

Ravel: The Complete Piano Concertos

Seong-Jin Cho

Deutsche Grammophon 00028948668205

Release date: 21 February 2025

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter