Marcel Proust wrote to Gabriel Fauré in 1897, “Monsieur, I not only love, admire and venerate your music, I have been, still am, in love with it.” In our first episode on the magnificent nocturnes of Gabriel Fauré we found passionate expressions rooted in Romanticism, a sounding poetry imbued with intimate and passionate lyricism.

Gabriel Fauré

Since the thirteen Nocturnes of Fauré were composed over a period of forty-six years, the first appearing in 1875 and the last in 1921, they show Fauré’s stylistic development. His early nocturnes mark the beginnings of the French piano school, while his later works are “entirely at ease with twentieth-century modernity.”

A scholar writes, “Fauré blossomed as he modelled his musical personality to an aesthetic fully integrated with the modernity of the twentieth century.” While some commentators feel that the nocturnes represent the summit of Fauré’s writing, others suggest that the late works are the result of his advancing years and his failing health. I suppose, that means that the nocturnes are of unequal quality to some commentators, but as a set, they offer a diverse panorama of the composer’s art.

Nocturne No. 7 in C-sharp minor, Op. 74

The Nocturne No. 7 in C-sharp minor, Op. 74 is dedicated to Adela Maddison, the wife of his British publisher. The work was composed during a trip to England and Wales, where Fauré was regally entertained by Elgar’s patron Leo Frank Schuster. Probably less well-known than the previous nocturne, it was nevertheless chosen as the Paris Conservatoire competition piece for women pianists in 1919. It is a mysterious piece featuring a hushed opening with a distinctive heartbeat.

Brooding and elusive, a slow-moving melody is superimposed over a faster inner voice. The opening is harmonically ambiguous, and the music reaches for a substantial climax and coda. The central section contains charming and uplifting music, full of unexpected twists and turns. This delightful segment features subtly developing motifs, and the return to the opening is accomplished by a spiralling sequence. The slow-moving melody returns before the music dissolves into thin air.

Nocturne No. 8 in D-flat Major, Op. 84, No. 8

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne Edition

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No.8 in D-flat Major, Op. 84, No. 8 (Pascal Rogé, piano)

The Nocturne No. 8 in D-flat major, Op. 84, No. 8, is not supposed to be a nocturne at all. It was included in a set of eight pieces (Pièces brèves pour piano) written between 1869 and 1902 and published as a set. In fact, the title “Nocturne” was added by the publisher Julien Hamelle, much to Fauré’s displeasure. We might reasonably call it a Moment musical, as it stands apart from the preceding works, as well as from the following serious and inward-looking Nocturnes.

Just because it is a short piece doesn’t mean it is any less interesting. True, the structure and intentions are rather simply as it unfolds in a single uninterrupted phrase. “From beginning to end, a running stream of fast notes is woven around the melody and its supporting voices.” The motion never stops and produces a shimmering swirl of movement and light. It is the last serene piece in the nocturne set, as Fauré turns to expressive concentration and the minor keys in his late nocturnes.

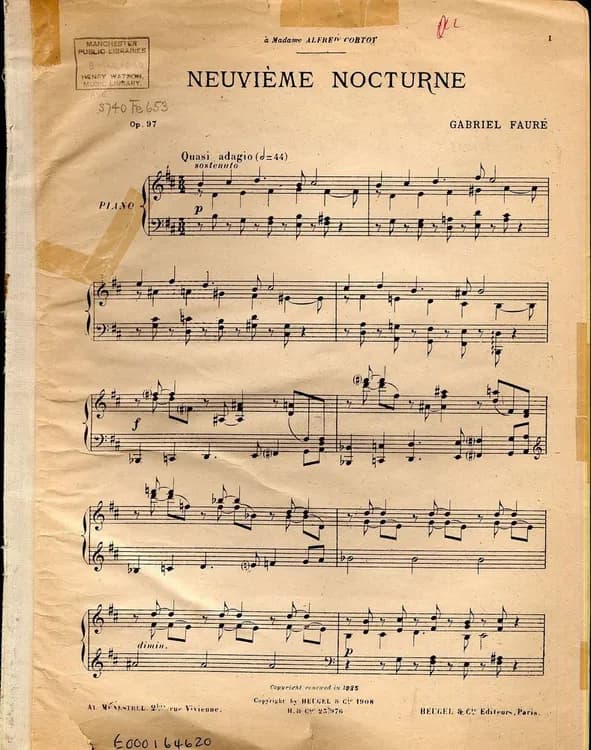

Nocturne No. 9 in B minor, Op. 97

Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No. 9 in B minor, Op. 97 (Théo Fouchenneret, piano)

Composed in 1908 and published in 1909, the Nocturne No. 9 in B minor, Op. 97, epitomises Fauré’s late style. The texture becomes sparse and the melody is devoid of ornamentation. Shorter phrases and modally inflected harmonic explorations combine with off-beat rhythms to bring a new seriousness to the genre. Sequences no longer just delineate transitions but become part of the melodic unfolding of a phrase to extend the discourse. It is formally less ambitious and streamlined, and lacks technical sparkle.

A noted performer writes, “The harmonic language is intriguing, with some use of a whole-tone scale and augmented chords, as well as unusual progressions. But the true striking feature is the wistful and introverted expression of this work (although it ends uplifted, in the major). It already bears the mark of a composer’s late style, as his means are economical and his thought abstract.” This new and demanding style has also been linked to Fauré’s hearing disorder, which worsened with age, possibly affected his compositions.

Nocturne No. 10 in E minor, Op. 99

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No.10 in E minor, Op. 99 (Marc-André Hamelin, piano)

The Nocturne No. 10 in E minor, Op. 99, features many similarities with the ninth nocturne, such as syncopation, melodic sequences and a more restricted formal layout. However, this work is ferociously intense, much darker and more explosive. There is a good deal of dialogue between the high and low voices, and a very pronounced bass line shifts the character into the deeper regions of the piano.

This nocturne concentrates on a single idea, as the short opening motive of the melody is extensively used throughout. The piece continuously builds tension and eventually reaches a powerful climax, which is completely dissolved in a calm coda. Fauré usually took his time completing compositions, but in the case of his 10th Nocturne, it only took him two days.

Nocturne No. 11 in F-sharp minor, Op. 104, No. 1

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne No. 11

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No.11 in F-sharp minor, Op. 104, No. 1 (Eric Le Sage, piano)

The Nocturne No. 11 in F-sharp minor, Op. 104, dates from 1913. It was written in memory of Noémi Lalo, wife of the music critic Pierre Lalo, and son of the composer Edouard Lalo. The piece is an elegy of restrained but clearly focused emotion. The beautiful, hesitant theme, “which attempts to rise but falls inexorably back, is developed to the point of abstraction, right up to a concluding of prodigious strangeness.”

The charm of his youthful pieces have given way to music of subtle and perfectly dissonant polyphony. The Gregorian modality gives the piece a character of resignation and despair, and the music only finds peace in the shimmering coda. This nocturne stands as among Fauré’s finest and most audacious works, and Alfred Cortot perceived “the dignity, the chaste and sorrowful reserve of the funerary monuments of antiquity.”

Nocturne No. 12 in E minor, Op. 107

Gabriel Fauré: Nocturne No.12 in E minor, Op. 107 (Eric Le Sage, piano)

The Nocturne No. 12 in E Minor, Op. 107, was published in 1916, and it places considerable technical demands on the performer. It is much larger in dimension than any other of Fauré’s nocturnes and the harmonic and melodic ambiguities make it the least accessible. In terms of its swaying rhythm, it might almost be called a barcarolle, but such a title is hardly suitable for such a serious piece.

The complicated opening, unfolding simultaneously on multiple levels, oozes like heavy perfume. Mysteriously, in the alternating section, the melody is syncopated on top of a running accompaniment in such a way as to make it virtually inaudible. Since the accompaniment and the melody rarely agree, we hear a great deal of dissonance. A commentator wrote, “The harmonic structure is fascinating and original, taking tonality to its limit while still maintaining a single key.”

Nocturne No. 13 in B minor, Op. 119

Gabriel Fauré’s Nocturne No. 13

Composed in 1921 and dedicated to Madame Fernand Maillot, the Nocturne No. 13 in G minor, Op. 119, was Fauré’s last piano work. One of the most inspired and beautiful in the series, the composer is casting a backward glance over the whole collection. “He produced what might be considered the archetype of the genre, as much in the expressive depth of the outer sections as in the powerful central storm.”

The composer Charles Koechlin claimed that this nocturne “is work dedicated to old age by a man whose brain and heart have not aged and who has kept all of his mental faculties intact.” The opening unfolds in the manner of a chorale, while the central “Allegro” features much virtuoso writing. The opening returns unchanged, and simply closes. According to Nancy Bricard, “this Nocturne achieves a perfect equilibrium between late-style simplicity and full-textured passionate expression.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter