The Muse, 1895 by Gabriel de Cool

© joshlangley.com.au

Given the context of 2020, many composers and artists have regretted not having created more; having been given the gift of time and not making the most of it. While there are many reasons for a lack of creative result, one is the black beast of all composers: procrastination. While it is truly not recommended to yield to temptation, there are some instances where the act of procrastination is a blessing, and quite a few composers can testify of it.

But what is procrastination? Procrastination is the act of delaying or postponing a task or set of tasks. Like the title of this article does not suggest, it is not the act of not doing something it is the act of pushing its completion to later. For many reasons, and the saying goes “il ne faut jamais repousser au lendemain ce que l’on peut faire le jour même” (never put off until tomorrow what you can do today), a composer would rather want to finish a piece of music on time, when the momentum exists and is at its peak. However, there are times when procrastination is beneficial; I call it taming the muse. Just like a wine benefits from time, procrastination allows ideas to mature, and just as a seed which is planted, slowly makes its way to a complete idea born of a multitude of external factors.

Gioachino Rossini has the reputation

of writing slowly

“Art is never finished, only abandoned.” is a quote by Leonardo da Vinci. Indeed, any composer — even the most perfectionistic — will take the decision, at some point, to leave the project as it is; it is calling the work finished. Sometimes the work is even left unfinished. Of course, Schubert comes to mind with two of his most famous works abandoned — namely his 8th Symphony and his Quartettsatz — and others include Mozart’s Requiem or Berg’s Lulu. The doubt that it has indeed reached perfection — does it ever? — is of course very present. Procrastination in the creative process is therefore the idea of going away from the creation — for an indefinite amount of time, be it a day or a few years. This time away from the work allows the mind to wander, the senses to stumble upon new ideas, the unusual to arise, the direction to change, other options to question the decisions and potential issues to be solved. Procrastination is very present in the creation of a piece of music; the simple observation of its timeline is a great testimony of it.

Wagner’s Tannhäuser was written 1842–45

and revised several times

Famous examples of works that have taken time to mature include Brahms’ first symphony (written between 1862-1876), Mahler’s second symphony (written 1888-1894) and Wagner’s Tannhäuser (written 1842–45; then revised several times in 1845, 1847, 1851, 1860-61, 1865, 1875!). Some composers, such as Rossini, even have the reputation of writing slowly, or under pressure. In the composer’s own words “only necessity takes precedence over inspiration”.

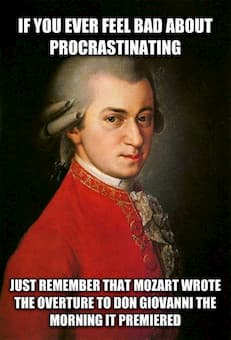

Although Mozart was a prolific composer, he had a reputation of being quite spontaneous and perhaps messy with his composition; he would write in bursts of inspiration and would be known for finishing works moments before their premiere — the overture for Don Giovanni was written the night before the performance.

There are productive days and there are less productive ones. But the days without a high creative output allow to rest the muse and come back with resources that are richer and more diverse. The game though, is to never stop creating, for instance by maintaining several fluxes of works; the days when a composer procrastinates with one piece allow his creativity to develop in another one. Procrastination — or taming the muse — is perhaps the real solution to the blank page.

There are productive days and there are less productive ones. But the days without a high creative output allow to rest the muse and come back with resources that are richer and more diverse. The game though, is to never stop creating, for instance by maintaining several fluxes of works; the days when a composer procrastinates with one piece allow his creativity to develop in another one. Procrastination — or taming the muse — is perhaps the real solution to the blank page.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter