George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel premiered his opera Serse on 15 April 1738 at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket in London. The composer had decided on a semi-historical plot involving the hot-blooded Persian tyrant Xerxes. It is a rather complicated plot, typical of Baroque opera. Serse is engaged to Amastre, who loves Romilda. Romilda loves Arsamene, Serse’s brother. Arsamene returns her love, but he is actually loved by Atalanta, Romilda’s sister. If you are looking for an opera with plenty of lovers quarrelling, jealousy around every corner, a bit of cross-dressing, and the occasion threat of execution, this opera is for you.

Italian Opera House at the Haymarket

Contemporary audiences, however, did not like it and the first production was a complete failure. It was even called “one of the worst things Handel ever set to music.” As a result, the opera disappeared from the stage for almost two hundred years and was only revived in 1924. “Today it is one of the most popular Handel operas, with the lightly ironic and occasionally farcical tone resonating with stage directors and audiences alike.” Let us listen to some of the best performances of the most popular and famous aria from Serse.

Handel: “Ombra mai fù” (Andreas Scholl)

Andreas Scholl

The opera proper opens with a short and rather strange aria.“Ombra mai fù” is a love song sung by Xerxes to a tree. This scene has a historical basis, as contemporary historians tell us. When Xerxes marched through Asia to invade Greece, he supposedly saw a magnificent tree by the roadside. Overwhelmed by its beauty, he decorated the tree with golden ornaments, and arranged that a man should be the keeper and guardian of that tree forever. In Handel’s opera it becomes almost comical, because as the operatic narrative unfolds, we quickly realize that Xerxes should have stuck with loving that tree.

Handel: “Ombra mai fù” (Cécilia Bartoli)

The aria is only 52 measures long, and prefaced by a short 9-measure recitative. Nevertheless, it inspired Handel to compose one of his best-loved melodies. In fact, you might have come across this aria in a number of arrangements for voice types, instruments, and ensembles under the title “Largo from Xerxes.”

Kathleen Ferrier

Tender and beautiful fronds

of my beloved plane tree,

let Fate smile upon you.

May thunder, lightning, and storms

never disturb your dear peace,

nor may you by blowing winds be profaned.

Never was a shade

of any plant

dearer and more lovely,

or more sweet.

Handel: “Ombra mai fù” (Kathleen Ferrier)

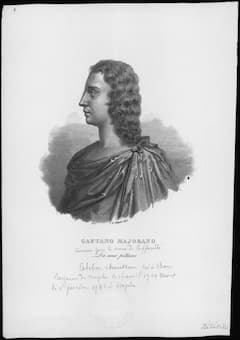

Caffarelli, castrato singer, the first Serse

As a matter of convention during Handel’s time, a soprano castrato would have sung the aria. This type of male singing voice is produced by castration of the singer before puberty. It prevents the male larynx from being transformed and the castrati combined the lungpower and breath capacity of an adult with child-sized vocal chords. That gave them extraordinary flexibility and a super-high tenor range with a “more falsetto-like upper register.”

Philippe Jaroussky

The gruesome practice of castration was prohibited and discontinued in 1870, and “Ombra mai fù” is typically sung in modern performances by a countertenor. I do like the performances by Andreas Scholl and Philippe Jaroussky because their high registers, performed almost entirely in falsetto register, create an almost angelic atmosphere. These types of voices are highly complex, and have been described as “Possessing an emotional coolness that produces an almost inhuman purity of tone.”

Handel: “Ombra mai fù” (Philippe Jaroussky)

Cécilia Bartoli

In modern performances, however, contraltos, mezzo-sopranos and even baritones also sing “Ombra mai fù.” While it is historically not entirely accurate, these alternate voice types add delicious flavours to this popular aria. Mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli always astonishes with her unusual tone colours. She is known for her “fully developed sumptuousness of the lower register, the vibrancy of the middle range…the top is limpid and powerful.” It is indeed wonderful to hear such powerful melancholy expressed in “Ombra mai fù.”

Dmitri Hvorostovsky

The contralto voice of Kathleen Ferrier seemed naturally suited to this aria, and its radiant and rich timber, “is enriched by velvety purple tones that reach deep into a manly range.” Besides the sheer beauty of her sound, Ferrier knew how to communicate. When you listen to her rendition of “Ombra mai fù” it sounds like she is singing to you and not really the tree. King Xerxes, as far as history can tell us, was of course a man. As such, we might call the operatic conventions around Handel’s time rather artificial. This begs the question of why this particular role could not actually be sung by a baritone?

Enter the great baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who’s voice was described as “redolent of luxury: beautiful tone, pinpoint intonation, elegant, and impassioned delivery.” The lyric qualities of Handel’s aria seem tailor made for Hvorostovsky’s voice, but when we hear the darker shades of his voice entering we also understand that the King of Persia was not an artificial cartoon figure. Now you know some of my personal favourite performances, which one is yours?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Handel: “Ombra mai fù” (Dmitri Hvorostovsky)

Andreas Scholl reaches places in the soul that none of the others quite reach.

I agree. In listening to several performances, I like his countertenor voice the best. I prefer the men performing it rather than Cecilia Bartolli.

I agree that Andreas Scholl reaches the most profound part of my soul, and tears well up in mt eyes each time I listen to him sing Ombra Mai Fu.

I have listened to Franco Corelli’S rendition of Ombra Mai Fu and It really impressed me

Moment magique!

MILLE MERCIS!

BAÏETA DE NICE

Andreas Scholl achieves perfection, which is so rarely attained in reality. A divine combination of voice, intellect, heart, humility, reverence, and dedication sets his performance of this aria apart from any other.

Jussi Bjoerling. Years ago I had a cassette tape of various selections with him. ombra ma fu was included. I can’t find his version now, but it was unbelievably beautiful.