The young Richard Strauss, age 22 (1886)

The lure of Italy to those who live in cold Northern Europe cannot be understated. Composer after composer went south and brought back their musical memories of that country of sunshine and warmth, of folksong and dance, and of landscapes from seaside to mountain.

The German composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949) followed that well-worn trail when he went on a tour of Italy funded by his father. At age 21, the talented young composer and conductor started his first job as Assistant Conductor to Hans von Bülow, leading the Meiningen Orchestra. That same year, 1885, he succeeded von Bülow as conductor when von Bülow suddenly resigned. His term as conductor only lasted 7 months but it is when Strauss made some of his seminal discoveries as a composer. He had learned the art of conducting from von Bülow, considered one of the greatest conductors of his age. Rehearsed by Strauss, the Meiningen Orchestra presented the premiere of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony and was able to present his own Symphony in F minor to the master. He also met the ideas and music of Wagner and Liszt, whose music had been despised by Strauss’ father. Now approaching it with an open mind and away from his home influences, he found inspiration in the ‘music of the future’ that would be influential for many years to come.

After he resigned from Meiningen, Strauss’ father funded a tour of Italy and he returned inspired to create his own tone poem on the country. Strauss spent the summer of 1886 composing and, in the autumn, started a new position as third conductor at Munich Court Opera, where his father played first horn.

Considered his first step in programme music (later to come to magnificent fruition in works such as Death and Transfiguration, Also sprach Zarathustra, and Till Eulenspiegel), Aus Italien, unlike those later one-movement works, is a symphonic fantasy in four movements.

The first movement, ‘Auf der Campagna’ is very Lisztian in its conception and construction. Strauss said it was his feelings at seeing the Italian countryside in sunshine, as seen from the Villa d’Este at Tivoli. The sun rises and the world is revealed.

Villa d’Este

Richard Strauss: Aus Italien, Op. 16, TrV 147 – I. Auf der Campagna: Andante (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Riccardo Muti, cond.)

The second movement takes us to Rome’s Roman past and its modern relics ‘In Roms Ruinen.’ The style here is much closer to Strauss’ other musical god: Brahms.

Arch of Septimo Severo in the Roman Forum

Richard Strauss: Aus Italien, Op. 16, TrV 147 – II. In Roms Ruinen: Allegro molto con brio (Dreseden Staatskapelle; Fabio Luisi, cond.)

In the third movement, we have Strauss’ first attempts at music musical pictorialism: the leaves move in the wind, the birds sing, and we have the sound of the sea at his feet as he stands on the shore in Sorrento (‘Am Strande von Sorrent’). Depicting nature was a new test for the young composer and this feels as though the hand of Berlioz is hovering over the work, although without Berlioz’ bombast!

The seaside at Sorrento

Richard Strauss: Aus Italien, Op. 16, TrV 147 – III. Am Strande von Sorrent: Andantino (Cleveland Orchestra; Vladimir Ashkenazy, cond.)

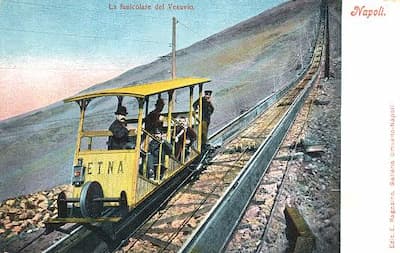

The last movement is the one that exposes the naïveté of the 22-year-old composer – he chose to base his movement on what he thought was a ‘Neapolisches Volksleben’ but turned out to be a song written only 6 years earlier by Luigi Denza, Funiculì, funiculà. The song celebrated the opening of the funicular railway at Mount Vesuvius and in 1880, its first year of sheet-music sales, sold over a million copies. Denza sued Strauss and won; Strauss had to pay him a royalty for the use of his in-copyright material. He wasn’t the only composer to fall into that trap, Rimsky-Korsakov made the same mistake using it in a 1907 composition, Neapolitanskaya pesenka (Neapolitan Song).

Can you imagine the work Strauss did to transcribe the song as he heard it, make his variation on the song, and then discovering he could have gone down to the corner shop and bought a copy? In his movement, Strauss adds all kinds of ethic touches, including the use of a tambourine for accents. We tend to laugh when we hear the movement today, since the source music is so familiar, but for Strauss, and probably for most Germans, who wouldn’t have known this song from the southern corner of Italy celebrating a local railway, for them, it was a touch of the music of the folk.

A postcard from 1902 showing the Vesuius funicular, closed in 1955

Richard Strauss: Aus Italien, Op. 16, TrV 147 – IV. Neapolitanisches Volksleben: Allegro molto (Dresden Staatskapelle; Rudolf Kempe, cond.)

Aus Italien was given its premier by the Munich orchestra in 1887 and has never achieved the popularity of Strauss’ later one-movement tone poems, but as his first steps into descriptive writing, it’s an exciting piece of work from the young Strauss that only hints at what he will achieve later.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Excellent article