A new book by Richard Beaudoin published in 2024 by Oxford University Press, Oxford Studies in Music Theory division, came to our attention recently. Sounds As They Are is a beautiful-looking hardback of 240 dense pages with musical examples, an extended discography, a list of works cited, and an index. He poses the question: In a recording what sounds count as music? The author, from a scholarly point of view, examines the ‘unwritten music’ or sounds in classical music that include those made by a musician’s body, technical noises, and how these sounds affect the listener’s experience.

Sounds as They Are © global.oup.com

I can recall recording sessions with the Minnesota Orchestra where we did our utmost to eliminate extraneous noises. We were afraid to breathe or to make any noise even from jewelry or belts rattling; I remember despite the carpeted conductor’s podium, Osmo Vänskä removed his shoes and then as a joke, the entire orchestra did too, and piled the shoes one on top of the others on his podium during a break; and the take ruined when a musician exclaimed, “YAY” after the brilliant ending of a piece without allowing for the obligatory few seconds of reverberation to dissipate is unforgettable. Of course, we all know of the vocalizations of Glenn Gould and others on historic recordings. That would never happen now… or are we missing something spontaneous?

Richard Beaudoin © music.dartmouth.edu

Beaudoin has analyzed and classified these sounds grouped into four categories: Sounds of breath including inhaling and exhaling; Sounds of touch including squeaks, foot noises on piano pedals, fingernail clicks, and percussive clacks; Sounds of effort including grunts, moans, panting, and the exultant holler (like our percussion player); and Sounds of surface noise.

Those of us of a certain age recall that the American composer and music theorist, John Cage, caused a sensation with his 1952 composition 4’33”—a piece performed in silence. His view was that the sounds of the environment and the ambient sounds of the hall should be considered with the music as a whole. Any auditory experience, in other words, may constitute music. The unique viewpoint arguably transformed the act of listening.

Beaudoin begins by offering thoughts through analogies from the art world in mediums such as film, photography, and painting. Rather than being “insignificant” they can be “distracting” but in an expressive sense. He offers thoughts on facial expressions in cinema—

“These rapid facial motions deliver expressive and often crucial information that would not be recorded in a written transcript of a given conversation. Just as facial micro-expressions offer valuable and often revealing information that enhances the meaning of spoken words, the placement and density of breaths, grunts, finger falls, and other non-scored sounds represent audio traces of physical activity…. suggesting ‘concealed emotions’…”

He goes on to use the analogy of oil paintings and the appearance of brush strokes, craquelure, (or the hairline cracks that can appear over time in an old painting), and those caused by painting en plein air (outdoors) where, “Several examples of plant material” seeds, grass, or sand, the imprint of an insect, and fingerprints can occur and can be compared, he suggests, to surface noise and fingernail clicks on a recording.

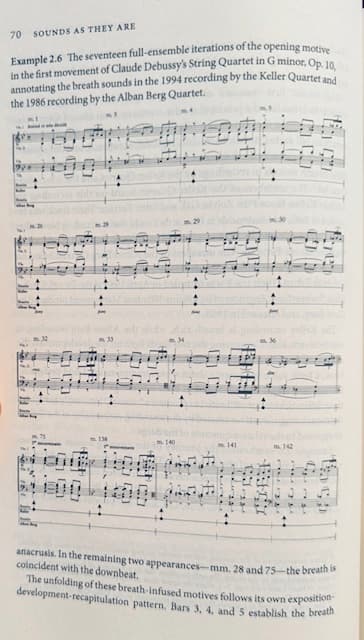

Numerous examples, charts, and photos follow as Beaudoin elucidates his concept. We see pages of musical examples marked to indicate where the artist or artists audibly breathe for phrases and climaxes. As a musician, I’d like to point out that breathing is essential to music-making. We not only breathe for the synergy with our fellow musicians, to feel phrases and direction in the music, but it is essential for a good ensemble between individual players. An intake of breath especially for an upbeat, will indicate the tempo and character of a piece. I think Beaudoin’s question is, when it is audible to the audience, does it detract from the performance or add to it?

The author depicts these breaths in Debussy’s String Quartet in G minor Op. 10, with the Alban Berg Quartet.

Chart I page 70

Claude Debussy: String Quartet in G Minor, Op. 10 – I. Animé et tres decide (Alban Berg Quartet)

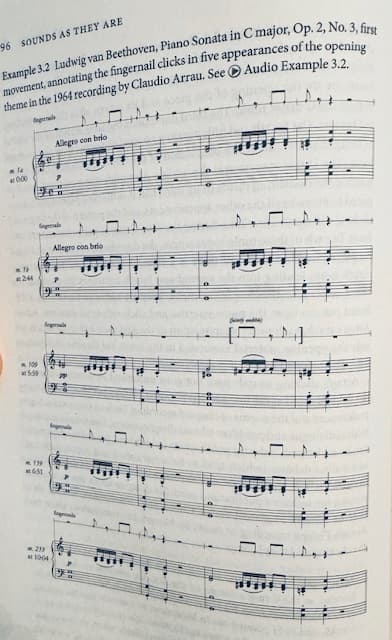

He notes Fingernail clicks, in the Beethoven Piano Sonata in C major made by performer Claudio Arrau .

Chart II Page 96

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 3 in C Major, Op. 2, No. 3 – I. Allegro con brio (Claudio Arrau, piano)

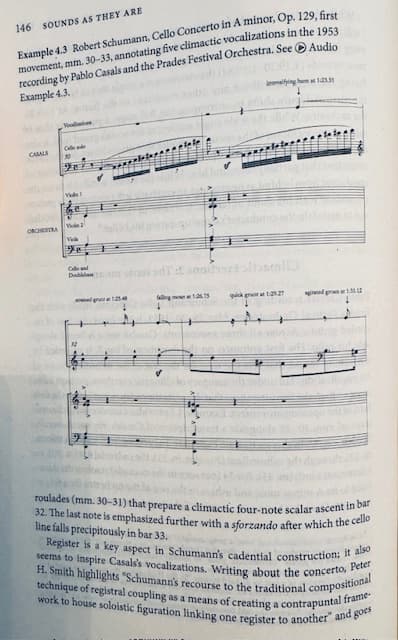

And he indicates the hollers, moans, and grunts during the performances, of cellist Pablo Casals in Schumann Cello Concerto.

Chart III Page 146

Robert Schumann: Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op. 129 – I. Nicht zu schnell (Pablo Casals, cello; Prades Festival Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

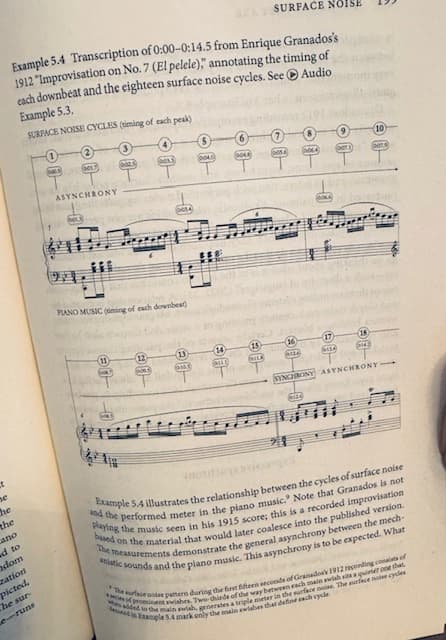

Finally, Beaudoin devises numerous different symbols to indicate various surface noises that may appear on the discs in a work for piano by Granados.

Chart final. Page 199

Here is the wonderful piece from Goyescas No. 7 El Pelele by Granados, performed by Jorge Luis Prats.

Granados El Pelele from Goyescas

The author offers his conclusions followed by a discography, an exhaustive list of works cited, and an index. He unfolds the tenets of a music theory—”inclusive track analysis—whose hallmark is the recognition of all sounds that appear on a given recording. He quotes Pauline Oliveros who was a guest at Beaudoin’s Introduction to Compositions course at Harvard University—

“At its best, music theory incorporates the same hypervigilant noticing that Oliveros championed across her lifetime of participation in music…and to accept the totality of audible events, whether they be on tracks or in the world.”

Beaudoin’s intensive research is impressive and exhaustive. The details may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but his premise begs the question: vocalization and breathing are human. When we hear these elements does it not add a humanizing quality to the music? Especially in the era of AI technology, do we not prefer to hear these sounds?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter