Global classical music audiences love music from Russia. It’s bold, it’s imaginative, it’s romantic.

Consequently, composers like Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov, Shostakovich, and others are beloved fixtures on concert programs, generations after their deaths. But those household names haven’t been the only great Russian or Soviet composers to excel!

Today, we’re tracing the history of two centuries of Russian music through the eyes of six prodigiously talented Russian women composers and paying tribute to their remarkable lives and stories.

Maria Zubova (ca. 1749-1799)

Maria Voinovna Zubova: I am Banished to the Desert

The composer, later known as Maria Zubova, was born in St. Petersburg around 1749 to the daughter of a vice-admiral. In 1782, she made an advantageous marriage to Afanasy Nikolaevich Zubov, Governor of Kursk.

She was known for both composing salon music and performing it. Unfortunately, though, not much of it was published. What was published appeared in 1770 in St. Petersburg when she was around thirty years old.

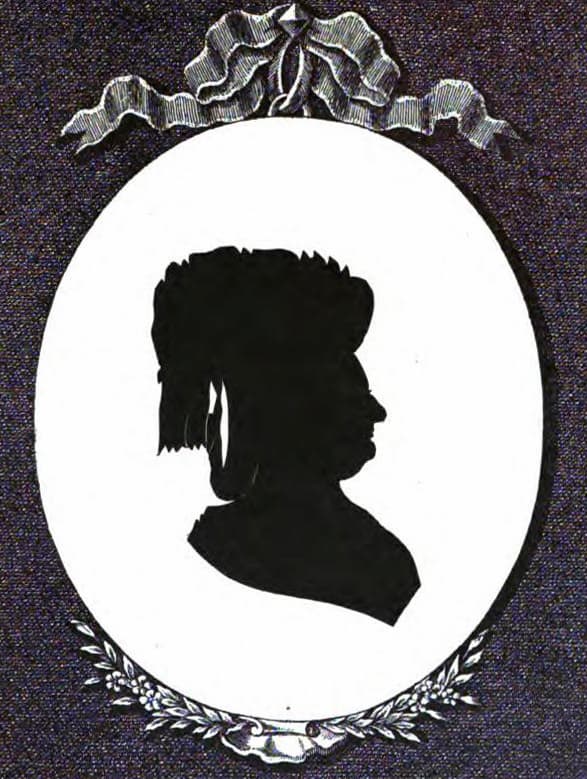

Maria Zubova

Her songs explore common Enlightenment tones and themes praising naturalness, the wholesomeness of the common people, folksong, and similar subject matter while still remaining smart and sophisticated.

Because of her rank in society, she did not appear much in public as a singer (it was considered unseemly for a wealthy or powerful woman to do so). However, she performed at many private parties.

Her performance abilities appear to have been second to none. Folklorist Mikhail Nikolaevich Makarov gave her high praise, calling her “the best singer in the early reign of Catherine II.” A lady-in-waiting to Catherine II called her “an intelligent and amiable woman.” The style of the time required performers to be well-versed in ornamentation and improvisation, skills that she was highly gifted at.

She died in the autumn of 1799 of a stroke during a card game with friends.

Natalia Kurakina (1766-1831)

Natalya Ivanovna Kurakina: Dérobe ta Lumière

Princess Natalia Ivanovna Golovina was born in Moscow in 1766 to a wealthy family. As a young person, she played guitar and harp, as well as sang.

We don’t know a lot about her early musical training, but she began performing her songs at salons at the age of 14 in 1780.

Natalia Kurakina

In February 1783 she married Prince Alexei Borisovich Kurakin and moved to the tsar’s court. In 1784, she had a son, and in 1787 and 1788, two daughters.

Although she was now a wife and mother, she did not stop performing in salons. In addition, her music was in demand. Her songs for voice and harp gained such a reputation that by 1795, the prestigious publishing firm Breitkopf published eight of them.

After 1800 she and her husband spent time in France and traveled throughout Europe. She kept a diary during this time that was published posthumously.

By the time of her death, she had 45 published songs attributed to her, the second-most of any Russian composer of her generation, male or female.

Ella Adayevskaya (Elisabeth von Schultz) (1846-1926)

Ella Adaiewsky: Berceuse Estonienne

Elisabeth von Schultz was born in St. Petersburg on 22 February 1846. As a child she studied piano with renowned piano teachers Anton Rubinstein and Adolf van Henselt.

She also studied composition. When she began to publish, she chose the pen name Ella Adayevskaya to pay homage to a kettledrum part from Glinka’s opera Ruslan and Ludmila (it featured the notes A, D, and A).

Elisabeth von Schultz

She had big ambitions. In 1873 she wrote a one-act opera named The Ugly Girl. Four years later, she wrote a four act play called Zarya. It was dedicated to the tsar but rejected by the censor.

Like many wealthy Russian women of her day, she moved leisurely around Europe. While traveling, she gave concerts. In 1881, she settled in Italy, and in 1911, in Neuwied, Germany.

She died in Bonn in 1926, leaving behind two operas, vocal music, and a handful of works for chamber ensembles.

Nadezhda Rimskaya-Korsakova (1848-1919)

Tchaikovsky arr. Nadezhda Rimskaya-Korsakova : Romeo and Juliet, arranged for piano duet

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture arranged for piano duet by Nadezhda Rimskaya-Korsakova.

Nadezhda Nikolayevna Purgold was born in St. Petersburg in 1848.

Nadezhda Rimskaya-Korsakova

She began playing the piano at nine and enrolled in the St. Petersburg Conservatory while still a child. She also studied theory, composition, and orchestration.

In 1868, she met composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and fell in love, and in 1872 they were married. Mussorgsky was the best man at their wedding! During the courtship, Nadezhda became close to Mussorgsky, as well as Borodin.

Over the course of her marriage, she became indispensable to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, personally and professionally. Initially, at least, she was better trained than he was, and she offered all kinds of advice and suggestions to improve his music.

She had seven children over the course of their marriage, and probably as a result, she gave up composing herself. But she remained a giant of Russian music.

Sometimes her expertise and her conviction in her own taste could backfire. At her husband’s funeral in 1908, Stravinsky was crying. She responded by asking, “Why so unhappy? We still have Glazunov.” Stravinsky later claimed this was the cruelest thing he’d ever heard.

But she cared deeply for her husband. After Rimsky-Korsakov’s death, she became the chief architect of his legacy, editing his autobiography for publication, as well as a variety of musical works.

She died of smallpox at 70.

Galina Ustvolskaya 1919-2006

Galina Ustvolskaya: Symphonic Poem No. 1

Galina Ustvolskaya was born in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) the year that Rimskaya-Korsakova died.

In 1937, when she was eighteen, she enrolled at the Leningrad Conservatory. Two years later, she became the only woman student in Dmitri Shostakovich’s composition class. He wrote, “I am convinced that the music of G. I. Ustvolskaya will achieve world fame,” and even went so far as to quote some of her music in his own. She studied with him between 1939-41 and then again after World War II, briefly.

Galina Ustvolskaya

That said, she was deeply independent, and she soon embarked on her own creative path, pointedly stepping out from Shostakovich’s shadow. She once said, “There is no link whatsoever between my music and that of any other composer, living or dead.”

Instead, she developed a violent, shocking style, and became known as “the lady with the hammer.” She composed – or at least shared – very little. But what she did write was earth-shattering.

A reappraisal of her work began when the restrictions around Soviet aesthetics loosened later in the Cold War. She died in St. Petersburg in 2006.

Only 21 of her pieces survive, not counting propaganda type work she made. Her music remains some of the most frightening and powerful of the twentieth century.

Sofia Gubaidulina 1931-

Sofia Gubaidulina: Offertorium

Sofia Gubaidulina was born to an engineer and a teacher in what is now known as the Republic of Tatarstan, 500 miles east of Moscow.

She started showing interest in music at the age of five. She graduated from the Kazan Conservatory in 1954, and later studied in Moscow.

Sofia Gubaidulina

At great personal risk, she and her fellow students hunted for scores and recordings of banned western music. In 1979 she was blacklisted, along with six other composers, for composing “noisy mud instead of real musical innovation,” according to the official denunciation.

Her reputation rose in the west, especially after violinist Gidon Kremer promoted her 1980 violin concerto Offertorium. In 1992, she moved to Hamburg, Germany, where she still lives.

Her music is associated with spirituality and religion, and she herself is a devoted member of the Russian Orthodox Church. She combines a religious, spiritual, or mystical focus with non-traditional elements in both her instrumentation and orchestration. The list of her awards and prizes is endless, and her music is still played all around the world, deeply beloved by audiences and performers alike.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter