The short piano pieces by Sergei Rachmaninoff are a treasure trove of Romantic brilliance. They stand as some of the most electrifying and soul-stirring works in the repertoire.

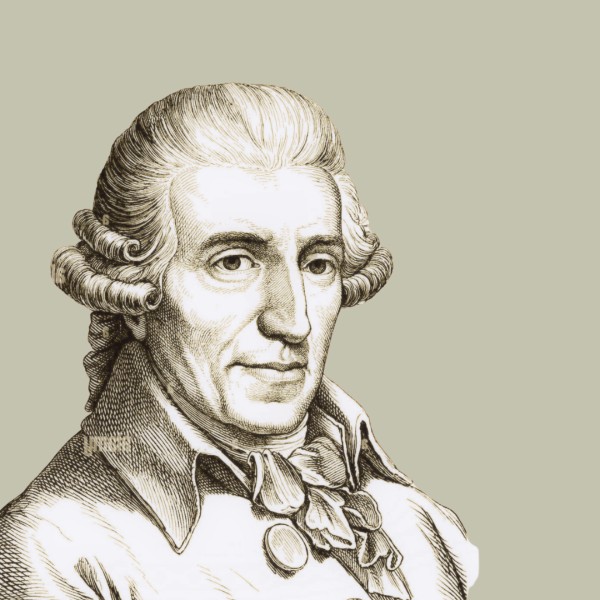

Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1901

Rachmaninoff blends jaw-dropping virtuosity with heart-wrenching emotion, ranging from thunderous chords to delicate whispers. He always infused his music with Russian melancholy, sweeping melodies, and a signature harmonic richness.

To commemorate his passing on 28 March 1943, we decided to dive into 15 of his most beloved piano miniatures which show the composer at the peak of his power.

Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No 2

Let’s get started with one of the most popular Rachmaninoff pieces ever. The Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3 No. 2, composed in 1892, was an instant crowd-pleaser. The bell-like opening chords and stormy middle section catapulted Rachmaninoff to instant fame.

Audiences and critics immediately latched on to its raw emotional power. Just listen to the ominous tolling notes summoning something ancient and unstoppable, only to be followed by a whirlwind of virtuosic fury.

It became so popular that Rachmaninoff reportedly grew sick of playing it, while fans demanded to hear it at every recital. Written when he was just 19, its haunting resonance and relentless intensity made it a signature piece.

Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5

The G-minor Prelude, Op. 23, No. 5 stormed onto the scene in 1903. Part of a ten-prelude set, it quickly became a fan favourite. Audiences and pianists were hooked from the start, as the stomping rhythm and bold melodic swagger made it a recital staple.

We are still mesmerised by the energy and craftsmanship of the piece as Rachmaninoff blends Russian flair with near-military precision. It did not achieve the fame of the C-sharp minor Prelude, but it became a go-to piece for pianists looking to flex both muscle and finesse.

Rhythmically, the piece is a beast, kicking off with a march-like pulse that’s all swagger. That main theme is sharp and insistent, while the lyrical and tender contrast is dripping with Rachmaninoff’s signature bittersweet lyricism.

Étude-Tableau in E-flat minor, Op. 39 No. 5

Unlike the flashy crowd-pleasers of his earlier days, the Étude-Tableau in E-flat minor, Op. 39 No. 5 sounds a darker, more introspective side. It dates from 1917, reflecting the turmoil of pre-revolutionary Russia and Rachmaninoff’s exile.

Reception was mixed at first as some critics found its brooding intensity and technical demands a bit much. Others hailed it as a haunting gem, a showcase of his mature style.

The opening sounds restless, almost claustrophobic, with its pulsing chords and relentlessly twisting melody. It’s almost like a storm brewing over a desolate plain. Technically, it is a nightmare of inner voices and overlapping lines, and pianists like Horowitz brought its smouldering passion into the concert hall.

Prelude in G-sharp minor, Op. 32 No. 12

The G-sharp minor Prelude, Op. 32 No. 12 didn’t take long to win over discerning listeners. It’s not really a barnstormer, but its shimmering and elusive quality makes it feel like a fleeting dream.

Rachmaninoff frequently performed the piece himself, and its delicate complexity showcased his softer side and evolving style. The piece quickly earned a cult following among pianists and fans.

It all starts with a rippling, almost impressionist figure in the right hand, set against a sparse, mournful left-hand melody. The minor tonality and subtle harmonic shifts provide a restless edge. It’s not a firework but all about atmosphere and a bittersweet hypnotic flow.

Étude-Tableau in D major, Op. 39 No. 9

The Étude-Tableau in D major, Op. 39 No. 9, sits as the finale of his second étude set. To many listeners, it landed like a firecracker in a quiet room. Critics and audiences were floored by its relentless energy and sheer pianistic bravado.

As expected, it quickly became a darling of virtuoso performers like Horowitz and Gilels, who relished the breakneck pace and thunderous chords. In a word, it’s the perfect showstopper.

The piece, with its leaping octaves and rapid-fire arpeggios, gallops in a syncopated rhythm like a runaway train. There is a brief lyrical gasp in the central section, but it’s quickly swallowed by the return of that maniac energy. If you’re looking for a technical nightmare, this is the explosive piece to turn to.

Prelude in D major, Op. 23 No. 4

Short and sweet, the Prelude in D major, Op. 23 No. 4 sounds a warm, understated charm that was quickly embraced by audiences and critics. Its gentle, lyrical glow doesn’t grab the headlines, but its quiet beauty is prized among pianists.

This is a piece full of elegance, with the opening floating over a soft and rippling accompaniment. Showcasing singing lines and delicate balance, the major tonality radiates a serene warmth.

However, Rachmaninoff can’t resist a few shadows, like the subtle chromatic turns in the tender middle section. It all sounds deceptively simple, but it is packed with inner voices that demand full finesse from the pianist.

Moment musicaux in E minor, Op. 16 No. 4

The Moment Musicaux in E minor, Op. 16 No. 4, part of his 1896 set of six, burst onto the scene with a fiery intensity that caught listeners completely off guard. Composed during financial strain and youthful ambition, it didn’t achieve instant fame.

Nevertheless, it quickly gained traction among pianists and audiences for its raw and restless energy. With plenty of virtuosic flair and emotional punch, it became a recital favourite and a standout in the Op. 16 collection.

Urgent, jagged, and unapologetic, the left hand churns out a furious ostinato while the right hammers away at a ferocious and desperate melody. And just listen to the spicy chromatic jolts that amplify the tension. It is a short technical sprint that demands precision and stamina.

Prelude in G major, Op. 32 No. 5

The Prelude in G major, Op. 32 No. 5 didn’t storm the stage like some of the flashier preludes but floated into the world with a serene grace that quietly captivated listeners. What a gentle and charming piece.

Rachmaninoff loved the poetic simplicity of the piece, making it a frequent part of his recitals. It has since become a beloved miniature showing the composer’s softer and more introspective side.

The piece sounds like a delicate dreamscape, with the lilting melody drifting over a murmuring accompaniment. Although the texture is light, it is nevertheless rather intricate, with arpeggiated figures weaving a hypnotic spell. It is effortlessly evocative and one of his most beloved piano pieces.

Étude-Tableau in C minor, Op. 39 No. 1

The Étude-Tableau in C minor, Op. 39 No. 1 launched Rachmaninoff’s second set of etudes in 1917. It turned out to be a stark and aggressive departure from the lyrical warmth of earlier works, and everybody was jolted by its ferocious energy.

Pianists quickly embraced it as a thrilling test of endurance, and its relentless pace and technical demands quickly made it a standout in recitals. While not universally adored, its raw power earned it a fierce following.

It’s like a tornado on overdrive: restless, dark, and borderline savage. The right hand spits out rapid and biting figures while the left hammers a relentless pulse, together building a wall of sound. It is vivid and almost chaotic, with snarling climaxes keeping the tensions high. There is no tidy narrative, but it is a technical beast with great emotional power.

Prelude in B minor, Op. 32 No. 10

The Prelude in B minor, Op. 32 No. 10 was inspired by the painting “The Return” by Arnold Böcklin. The music has an evocative, almost narrative quality and features great melancholic depth and echoes of Russian nostalgia.

Rachmaninoff frequently played this piece during his own recitals, and its reception grew into quiet reverence. Once again, Rachmaninoff was able to turn personal musings into universal resonance.

The minor tonality sets a mournful stage, opening with an elegiac melody over a restlessly rippling accompaniment. Arpeggios shimmer like reflections, and chromatic shadows hint at loss and longing. After a central passionate outcry, the music sinks back into a hypnotic and desolate flow.

Prelude in B-flat major, Op. 23 No. 2

Often called a mini-concerto in disguise, the Prelude in B-flat major, Op. 23 No. 2 stormed onto the scene in 1903. Its bold and heroic sweep, not to mention its virtuosic dazzle, made it an instant hit.

Rachmaninoff’s own performances fuelled its popularity, cementing it as a glittering showcase of his early compositional strength. With its fierce dedication towards blending power and elegance, it instantly became a crowd-pleaser.

It is a marvellous fanfare of unshakeable confidence, with the left hand driving a relentless accompaniment while the right unleashes cascades of chords and glittering runs. It offers a lyrical sigh in the middle section, but the opening bravado returns thicker and even louder.

Prelude in E-flat major, Op. 23 No. 6

The Prelude in E-flat major, Op. 23 No. 6 is a gentle masterpiece, full of lyrical warmth. Its tender elegance made it an immediate favourite, and its understated charm earned it a special place in recitals.

It doesn’t demand the spotlight like his flashier preludes, but Rachmaninoff himself was drawn to its singing lines and delicate poise. In fact, it has been called a “gem of restraint.”

The music has the character of a lullaby, with a serene melody gliding over a smooth and rocking accompaniment. The left-hand pulse cradles the cantabile phrases, weaving a spell of pure calm. Subtle chromatic dips add a faint ache to the sweetness, sounding like a fleeting moment of peace in a restless world.

Prelude in F minor, Op. 32 No. 6

The Prelude in F minor, Op. 32 No. 6, part of his 1910 set of thirteen preludes, earned a place in the spotlight with its restless and enigmatic energy. Yet, the dark and elusive energy is not overwhelming but rather intriguing.

It became a favourite among pianists, including Rachmaninoff himself, who relished its technical challenges and moody flair.

The piece is certainly twitchy, and the syncopated theme darts over a jagged and pulsing bass. We find rapid runs and abrupt chord stabs while the harmony provides an uneasy association with the minor key. It is fast, precise, and unforgiving, demanding nerves of steel from any and all pianists.

Moment Musicaux in B minor, Op. 16 No. 1

The Moment Musicaux in B-flat minor, Op. 16 No. 1, the opener of his 1896 set of six, arrived with a quiet intensity. Written during a lean period for the young composer, it didn’t explode into fame like his later hits, but it nevertheless found a receptive audience.

Pianists and listeners are drawn to its sombre beauty and subtle craft, with a mournful minor melody that drifts over a steady, hymn-like pulse.

The minor harmony provides a natural gloom, with chromatic sighs deepening the melancholy. There is a loose, rhapsodic arc that lets the music breathe and wander without rushing. A brighter flicker in the central section provides some hope before the music sinks back into the shadow of a resigned hush.

Moment Musicaux in D-flat Major, Op.16 No. 5

Part of the Op. 16 set, the Moment Musicaux in D-flat major quietly offers reflective grace and tender beauty. Its introspective glow earned it a warm if sometimes understated, reception among pianists and early audiences.

Over time, its gently growing lyrical depth became a cherished breather within the universe of Rachmaninoff’s beloved piano pieces, and the work seems to shine brighter with every listen.

It has been described as a “soulful exhale,” with the gentle melody swaying over a hushed accompaniment. Subtle chromatic touches add a bittersweet feel, and the music drifts like an unfolding memory. The middle section is slightly livelier, but it soon settles back into the quiet reverie of the opening.

Bonus Track: Prelude in C minor, Op. 23 No. 7

Bust of Sergei Rachmaninoff

Let’s finish this collection of the 15 most beloved piano pieces by Rachmaninoff with a bonus track sounding the fierce and unrelenting energy of the Prelude in C minor, Op. 23 No. 7. Critics and audiences were immediately struck by its dark and propulsive drive.

The music is relentless indeed, charging in with a staccato minor theme that is sharp, insistent, and brooding. It has a wonderfully dense and kinetic texture with a churning left-hand pulse driving a right-hand barrage of chords and darting runs. The brief middle section is even stormier, with Rachmaninoff seemingly channelling chaos into precision.

Rachmaninoff’s 15 most beloved piano works stand as a testament to his unmatched ability to fuse raw emotion with staggering technique. From his early triumphs in the 1890s to his mature reflections of the 1910s, Rachmaninoff won over generations of music lovers and pianists with his technical wizardry, brooding intensity, and introspective beauty.

While pianists adore the technical challenges and expressive depth, listeners are hooked by Rachmaninoff’s vivid storytelling. I think you would agree that Rachmaninoff could make the piano speak like no other.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter