The Belgian string quartet, Quatuor Danel has released many recordings of standard string quartets, but they are celebrated for their performances and recordings of the Fifteen Shostakovich String Quartets—their second set recently released on the Accentus Music label. They are advocates as well of the lesser-known and astonishing seventeen string quartets of Mieczyslaw Weinberg.

Quatuor Danel

The Polish Soviet composer and pianist was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1919. An exceptional performer, he became a touring pianist after his extensive studies of both the keyboard and composition. On the heels of the Nazi invasion in 1939, Weinberg, threatened due to his Jewish heritage, escaped on foot, wandering in the countryside, witnessing the carnage, and made his way through several towns across the border to Minsk. There, he was granted permission to study at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied with eminent Russian composers Rimsky-Korsakov and Balakirev. Shortly before he was to graduate, in 1941, Weinberg had to flee once again as the German incursion was imminent. He escaped to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, some 2,000 miles away. Fortunately, his skills led to a position with the Uzbek SSR State Opera and Ballet Theatre. By a twist of fate, a former Leningrad Conservatory colleague who had been a teaching assistant to Shostakovich was evacuated to Tashkent. After hearing Weinberg’s First Symphony, he contacted Shostakovich and asked him to review Weinberg’s Symphony. Shostakovich was quite impressed, and he managed to arrange for Weinberg to come to Moscow, as Jewish People needed special permits to live there. Weinberg venerated Shostakovich, and the latter thought Weinberg was “one of the most outstanding composers of today.” They became fast friends.

The political climate made life more and more perilous for artists. Some of Weinberg’s music was banned, as were the works of other composers. It is horrifying to note that Weinberg, during a Jewish purge, was accused of conspiracy and arrested in 1953. It was only due to Shostakovich’s intervention with Stalin, at great personal risk, that Weinberg was eventually released. Weinberg’s music reflects the persecution and his experiences during WWII. His parents and sister, as well as other relatives, were murdered.

Weinberg decried hate, racism, and repression. Yet Weinberg’s huge output is far from all morose. Mieczysław Weinberg’s astonishing compositions number over 150 works, including 26 symphonies. I must mention his Cello Concerto in C, Solo Cello Sonatas No. 1- 4, the 24 Solo Cello Preludes, and the 17 string quartets (Discover more from our previous article “There’s More to the Solo Cello Repertoire Than You Might Think!”). Unhappily, since his music was unavailable outside the USSR, his music remained shrouded in obscurity until relatively recently.

My conversation with Marc Danel revealed so much about Weinberg’s music.

What stands out for you in the Weinberg works?

Weinberg is undoubtedly one of the greatest composers in music history. His works, much like those of Shostakovich and Beethoven, narrate profound stories, leaving you changed after each piece. He was exceptionally inventive, often ahead of his time.

Mieczysław Weinberg: The String Quartets (Quatuor Danel)

I would describe Weinberg’s music as deeply sincere and emotionally charged, inventive and full of strong human emotions. Weinberg truly, I would say, ‘allowed’ himself to do anything he wanted, so his compositions push boundaries and are full of surprises and imagination. His unconventional approaches to musical form, such as in Quartet No. 6, defy conventional norms. It has six movements, while Quartet No. 15 is in nine movements, and the movement indications are merely metronome markings, “quarter note = 68” and not “Allegro or Andante.” There are quartets in one movement as well.

Mieczysław Weinberg: String Quartet No. 15, Op. 124 – IX. quarter note = 60 (Quatuor Danel)

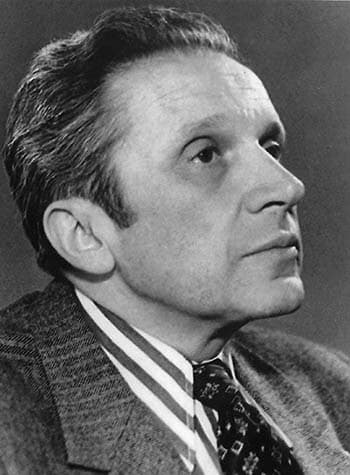

Mieczysław Weinberg

Performing Weinberg creates a palpable shift in the audience. The air somehow feels different, akin to the transformative impact of Shostakovich and Beethoven’s works, a transformation that is quite difficult to translate into words.

We often draw parallels between Beethoven and Schubert’s relationship and that of Shostakovich and Weinberg. While Shostakovich’s work is marked by perfect proportions, Weinberg, like Schubert, envelops the listener in unique atmospheres, immersing us in a distinctive characterization or nuance for extended periods of time. To illustrate Weinberg’s individual style, the first movement of Weinberg’s ninth quartet, for example, maintains immense intensity over its more than ten-minute length. It’s double forte throughout (very loud) except for a triple forte designation at the end, while in contrast, the eleventh quartet creates a unique soundscape by asking the performer to play two and a half out of the four movements with a mute. Even the movement without a mute doesn’t exceed mezzo piano (moderately soft). That is, extended and formidable tension on the one hand, versus a kind of whispered excitement!

Mieczysław Weinberg: String Quartet No. 11 in F Major, Op. 89 – II. Allegretto (Quatuor Danel)

Whenever I play Beethoven’s Op. 130 String Quartet, Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 2, or Weinberg’s Quartet No. 6, I am amazed. I feel incredibly lucky and never take it for granted.

Mieczysław Weinberg: String Quartet No. 6 in E Minor, Op. 35 (Quatuor Danel)

The rhythmic complexity and intensity of the Scherzo to Quartet No. 5 is breathtaking, and it’s only two minutes!

Weinberg: Quartet No. 5 – Scherzo

How do you approach learning a work that is new to you?

It very much depends on what “new to us” means. For instance, if we were to learn a piece we have not played before, such as Ligeti‘s Quartet No. 2 (having extensively played Ligeti’s Quartet No. 1), we would approach it with all the surrounding knowledge from our previous work on Ligeti’s first quartet, as well as on the six Bartók quartets. We would immerse ourselves in as much information as possible, listening to recordings and learning from those who worked with Ligeti.

Can you tell us how you were able to acquire all the scores of the Weinberg quartets, which led to the complete recording?

When we recorded Weinberg, the process was even more intense. We premiered several of his quartets, including Quartet No. 3, No. 6, No. 14, and other pieces like the beautiful “Aria,” “Capriccio,” and “Improvisation & Romance”.

Mieczysław Weinberg: Aria, Op. 9 (Quatuor Danel)

It was a monumental task, starting with finding the parts. Here’s a little anecdote: we couldn’t locate sheet music for Quartets No. 1, 2, 3, and 5. Inspired by Shostakovich’s widow Irina, my wife and I visited Olga Weinberg, Weinberg’s widow, and explained our struggle in finding the scores.

She went searching and returned with the original manuscripts. Much to our astonishment, she gave us permission to make copies of them. This was in Moscow in the 1990s, a time when it wasn’t the safest place to carry valuable manuscripts on the metro, and we carried four of them in our bare hands!

We meticulously copied them, handwriting our own parts on blank music sheet paper, and subsequently, we recorded them all from 2007-2012. I still play from those parts I transcribed nearly 30 years ago.

Understanding Weinberg’s style required extensive research and thoughtful interpretation, blending elements that connect with Shostakovich as well as other composers while forging an approach as specific to Weinberg’s music as possible. We did have the Borodin Quartet’s recordings of some of Weinberg’s quartets to listen to, but most often, it felt to us like we were pioneers, as if we were a quartet of archaeologists taking on the role of researchers and carefully gathering evidence to guide us through a decisive interpretation. Our aim was to replicate the original text as much as possible, one that closely mirrors what Weinberg would have envisioned for his string quartets.

How is a rehearsal of a quartet led? How is this different in a recording session?

We all lead it. I think every quartet, much like every family, couple, team, or sports team, has its own internal dynamics. Our dynamic is very egalitarian—we have absolutely no hierarchy. I suspect this is true of 95% of quartets playing today. The historic model of a quartet led by a teacher with three student followers is a thing of the past.

That said, discussing music can be challenging. Sometimes, we might agree on something, but when we try to explain it, it feels like we’re not on the same page. Although we do communicate a lot, as a group, we strive to interact through our playing rather than focusing on verbal instructions—that is, we aim to play more and talk less. As to how we rehearse, we enjoy slow work, where we focus intently on sound (aiming to sound like an organ) and intonation. Sometimes, we might exaggerate the musical intentions during slow practice to enhance the final interpretation, which helps us emphasize and understand the composer’s musical intentions more deeply. This overemphasis on the character under tempo helps us build the final result.

When disagreements arise, we try to be as honest as possible. If one of us suggests a certain way of playing or a particular tempo, and another proposes something different, we try both approaches. Ultimately, we might take a vote, and if it’s a tie, we’ll find a compromise.

Recording sessions are quite different. Since we record live, our recordings are essentially concert performances, with minimal edits afterwards. During a recording session, we must minimize talking. We’ve been fortunate to work with exceptional sound engineers, including Barbara Valentin from WDR in Köln, with whom we recorded all the Weinberg Quartets, and Vilius Keras, with whom we recorded the Shostakovich quartets and, more recently, the Prokofiev quartets. The experience with them has been incredible. Vilius, a talented musician himself, has an incredible capacity to understand our intentions like a mind reader. When we record, we are content to place our trust in the person behind the microphones, which has always been a good choice.

How do you think the Danel Quartet communicates the emotions that you encounter in the composer’s work?

Quatuor Danel

It’s difficult to assess how we communicate from the audience’s perspective. We continually strive to understand the composer’s intent and make it our own. Consider how someone’s tone of voice in calling your name can change the meaning—it might be said with anger, relief, frustration, or delight. The sound fosters different outcomes, depending on the situation. Likewise, once we grasp what the composer wanted, we decide on the colour of the sound. In that sense, colour really is the first choice we make as a quartet when communicating emotions.

There are many other considerations too, such as the construction of the piece, the variations in intensity, articulation, or tempo, as well as how we interact with each other (which is an essential component of any professional string quartet).

Here’s a movement from Quartet No. 9 that is mainly pizzicato and has a mischievous and sardonic quality—an example of the variation of intensity, mood, and articulation you were alluding to.

Mieczysław Weinberg: String Quartet No. 9 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 80 – II. Allegretto – attacca (Quatuor Danel)

It’s crucial that our performance feels spontaneous as if we are improvising what is written. We try never to give the impression that we are merely reading the notes of the score and reciting them to the audience. Our aim is to ensure that our playing comes from within us. Every time we are on stage, translating the music through a human lens is what we attempt to do!

If we believe wholeheartedly in our approach, we feel we can commit ourselves entirely to its execution. Any performer on stage must acknowledge that their style may not resonate with all audience members. As a quartet, our primary concern is to ensure that we are genuine, giving everything we have down to the last drop of sweat. We strive to be honest in our performance and to convey our deep passion for this music.

What are your plans looking forward?

One of my sincere aspirations is to re-record Weinberg’s works. Our set of recordings was completed in 2009. Given that it’s been 15 years since then, I believe it’s time to revisit and capture how we have evolved since those initial recordings. And I think we hope to continue introducing audiences to these great works.

It’s certainly gratifying to see other ensembles learning and performing Weinberg’s quartets, and we hope our efforts have helped pave the way for recognition of Weinberg’s remarkable music. As pioneers and interpreters of this great music we think we are so fortunate to have one of the most amazing jobs in the world.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter