“He moved those without understanding to mindless admiration”

Pierre Rode

The three great representatives of the classical French violin school, Rodolphe Kreutzer (1766-1831), Pierre Baillot (1771-1842), and Pierre Rode (1774-1830) essentially established the history of modern violin technique. Rode was probably the most finished representative of that particular school, and Boris Schwarz writes, “he imbued performances with characteristically French verve, piquancy and a kind of nervous bravura.”

In 1803, Kreutzer, Baillot, and Rode jointly authored the Méthode de Violon, an instructional text that summarised the innovations in technique and playing style and the resulting modifications in violin construction and bow production. This violin method was officially adopted at the Paris Conservatory, and it furnished the foundations for the French violin school and standardised instruction.

Pierre Rode: 24 Caprices, No. 1-12 (Oscar Shumsky, violin)

Rode’s artistic growth took place during the revolutionary decade, “and it is not surprising that his music is akin to that of Cherubini and Méhul and the operas of the 1790s; there is declamatory pathos, martial dash and melting cantilena.” Mirroring a trend in French music of this period, Rode certainly had a gift for lyrical, often melancholy melodies. According to Schwarz, “this made his music particularly attractive to German early Romantic composers.

Pierre Rode: Violin Concerto No. 7 in A minor (Friedemann Eichhorn, violin; South West German Radio Kaiserslautern Orchestra; Nicolás Pasquet, cond.)

In the Beginning

Pierre Rode’s Caprice No. 2

Jacques Pierre Joseph Rode was born in Bordeaux on 16 February 1774. Musically precocious, he received his initial violin instruction from André-Joseph Fauvel, a student of Pierre-Noël Gervais, a native of Mannheim. Rode started performing publicly at the age of 12, and Fauvel decided to take his gifted student to Paris.

Once arrived, Rode quickly met Giovanni Battista Viotti, who had brought the last great flowering of the Italian tradition originating with Corelli to the French Capital. Viotti was overjoyed to accept Rode, and he soon became the master’s favourite student. Rode first appeared in the Concert spirituel on 5 April 1790 performing his teacher’s Violin Concerto No. 13. The performance was a great success, and since Viotti no longer played in public, he entrusted Rode with the premiers of his Concertos Nos. 17 and 18.

Giovanni Viotti: Violin Concerto No. 18 in E minor

Paris Conservatoire

By 1795, Rode was appointed professor of violin at the newly founded Conservatoire, but almost immediately engaged in extended tours to the Netherlands and Germany. When he first appeared in Hamburg, Ernst Ludwig Gerber heard “a violin player of the first rank with respect to his outstanding tone, his extraordinary dexterity, and his tasteful performance style.”

After a brief and unsuccessful appearance in London, Rode returned to his duties at the Paris Conservatoire. However, he was quickly on the move again and during a trip to Madrid, he became friends with Luigi Boccherini. Some sources suggest that Rode’s Concerto No. 6, dedicated to the Queen of Spain, “profited from Boccherini’s advice.”

Pierre Rode: Violin Concerto No. 6 in B-flat Major (Friedemann Eichhorn, violin; Jena Philharmonic Orchestra; Nicolás Pasquet, cond.)

International Reputation

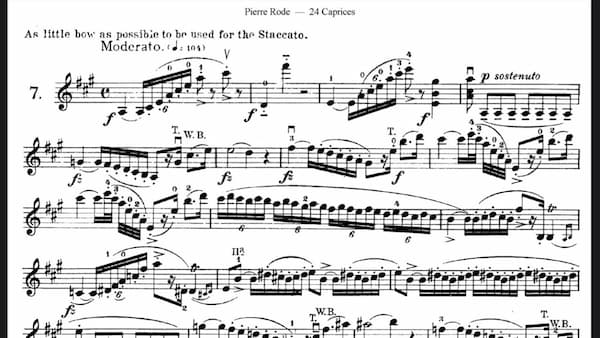

Pierre Rode’s Caprice No. 7

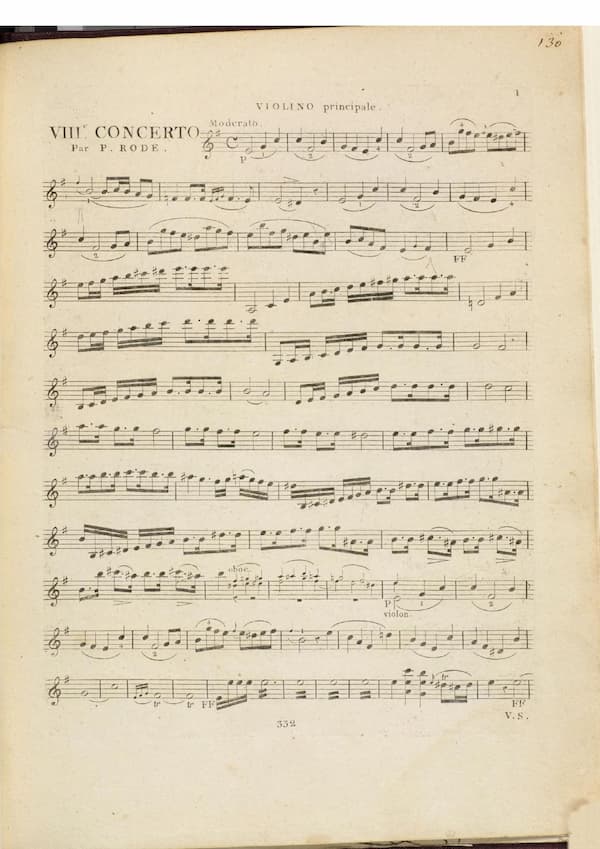

Rode was appointed to the post of solo violinist in the private orchestra of Napoleon Bonaparte, and he introduced his Seventh Concerto with great success. But what is more, he established an international reputation as a violin virtuoso and composer. In 1800, the AMZ in Leipzig reported, “The mass of foreign virtuosos who took part in our concerts heard with amazement that the most perfect violin player of Europe was in Paris. Not only we, but they also declared that this man was Mr. Rode, whose modesty and unpretentiousness are equal to his talents.”

Rode entered into a virtuoso competition with Rodolphe Kreutzer, and the report concluded, “Rode’s artistry seems to have been more inborn in him. He surmounts the greatest difficulties with the greatest ease and naturalness, like the naturalness of his always-upright behaviour.” Beginning in 1803, Rode departed on an extensive tour through Central Europe with St. Petersburg as his final destination.

Pierre Rode: Violin Concerto No. 1 in D minor (Friedemann Eichhorn, violin; Jena Philharmonic Orchestra; Nicolás Pasquet, cond.)

Declining Fortunes

The young Louis Spohr heard Rode in Brunswick, and his playing was a revelation. As he wrote in his Memoirs, “the more often I heard him, the more I was captivated by his playing. Yes, I soon had no reservations about ranking Rode’s playing.” Rode remained in Russia for four years, and as solo violinist to the tsar enjoyed extraordinary popularity. However, upon his return to Paris, his star had begun to fade.

His newest compositions did not please the public, and a critic suggested that “the cold Russian climate had not remained without influence on his works.” In addition, his playing “inspired on the whole, little enthusiasm.” Although he decided to no longer appear in public, he resumed his European travels in 1811, and in December 1812, gave the first performance of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata Op. 96. Beethoven wrote the violin part specifically for Rode, but in the end, the composer was disappointed.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96

Retirement and Death

By 1814, Rode had married and settled in Berlin. He still performed occasionally but focused on composition and teaching. He composed his famous 24 Caprices, and taught Eduard Rietz, later the violin teacher and close friend of Felix Mendelssohn. Rode returned to France in 1819 and settled in his native Bordeaux.

He occasionally performed in the French countryside, and he made an ill-advised attempt at a comeback in Paris in 1828. The concert was a complete fiasco, and critics wrote, “bowing and fingering were timid… he had in himself lost the confidence in his power. Out of respect, people applauded but only as if out of obligation.” Rode suffered a stroke in 1829 that left him paralysed, and he died on 25 November 1830.

Pierre Rode: Violin Concerto No. 13 in F-sharp minor (Friedemann Eichhorn, violin; South West German Radio Kaiserslautern Orchestra; Nicolás Pasquet, cond.)

Musical Legacy

Pierre Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 8

Pierre Rode composed 13 concertos, accepted by “the entire generation and respected even by Beethoven.” These concertos had some significance in the development of the Romantic concerto, but they are nowadays rarely performed. Rode also composed roughly 12 string quartets and a number of Duos, but his most important work is doubtlessly the 24 Caprices en forme d’études.

First published in 1815, every Caprice in Rode’s set is eminently a miniature work of art as well as a technical challenge to the violinist. That particular notion is confirmed by Andreas Moser, a student of Joseph Joachim, who wrote, “their value, however, was not exhausted by their didactic purpose but extended to their musical substance.”

Pierre Rode: 24 Caprices, No. 13 in G-Flat Major (Oscar Shumsky, violin)

As with many sets of études, Rode explores all major and minor keys, starting his instruction in C Major. The Caprice No. 1 serves as a structural and musical model for much of the remaining set. It opens with a beautiful slow “Cantabile,” and eventually springs to life in a highly energetic “Moderato” section. This balance of musical and technical needs has become an indispensable part of the violin curriculum.

When Niccolò Paganini heard Pierre Rode perform in Rome in October 1820, he wrote, “the monarch of variety…even in the antechamber of Paradise, it could not sound better than he…” Rode introduced a new kind of instrumental lyricism in his Air Varié Op. 10. It was transcribed by Johann Baptist Cramer, and the great singers frequently use it as a vocal display piece. And let’s not forget that Rode greatly influenced a succession of younger violinists, chiefly among them, Louis Spohr who adopted his style and developed it further.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Pierre Rode: Introduction et variations brillantes, “Air tyrolien” (Friedemann Eichhorn, violin; Jena Philharmonic Orchestra; Nicolás Pasquet, cond.)