The Parisian café-concert established itself during the Second Empire as a standard diversion of the urban bourgeoisie and working class by providing a combination of dinner and song. Offering entertainment provided by strolling entertainers singing drinking-songs, along with refreshments at a café were found to attract customers. As the café-concerts gained the right to host costumed performances, it added short plays and dance numbers. One generally expected a program divided between a vaudeville portion, revolving around sung individual performances and one or more theatrical presentations. The informal atmosphere, the skimpy dresses and the suggestive nature of certain songs could not escape criticism. A reporter wrote: “What a stench of tobacco, spirits, beer, and gas all mingled together. It was the first time I had entered such a place, the first time I saw women smoking in a café. On the stage one witnessed inferior subject-matter, little voices that brayed and meowed — there is nothing that could justify the surcharge on one’s glass of beer.”

The Parisian café-concert established itself during the Second Empire as a standard diversion of the urban bourgeoisie and working class by providing a combination of dinner and song. Offering entertainment provided by strolling entertainers singing drinking-songs, along with refreshments at a café were found to attract customers. As the café-concerts gained the right to host costumed performances, it added short plays and dance numbers. One generally expected a program divided between a vaudeville portion, revolving around sung individual performances and one or more theatrical presentations. The informal atmosphere, the skimpy dresses and the suggestive nature of certain songs could not escape criticism. A reporter wrote: “What a stench of tobacco, spirits, beer, and gas all mingled together. It was the first time I had entered such a place, the first time I saw women smoking in a café. On the stage one witnessed inferior subject-matter, little voices that brayed and meowed — there is nothing that could justify the surcharge on one’s glass of beer.”

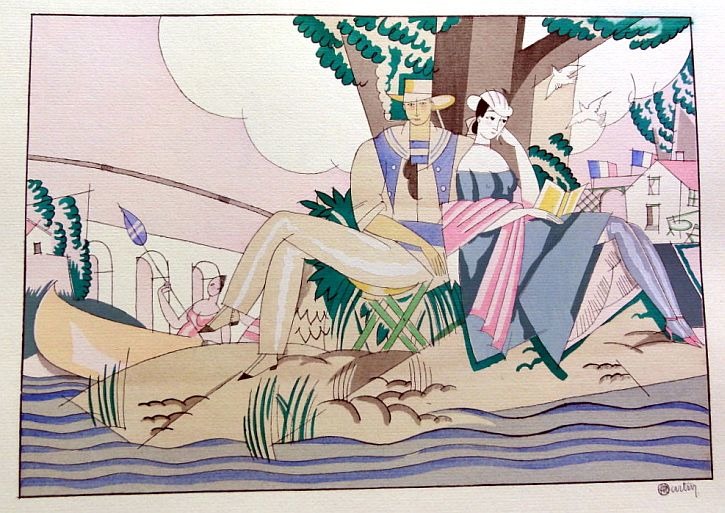

Parade. Ballet réaliste en un tableau

Around the turn of the century the café-concerts gradually expanded to include dance numbers, acrobats and other attractions from circus, sports arena and fairgrounds, including boxing kangaroos and human calculators. In 1899, a columnist for the ultra-conservative Le Gaulois bemoaned the decline of the café-concert. He writes, “Without apocalyptic metaphor, the aesthetic of the café-concert is truly a sad affair. Observe a program from one end to the other — in which a drunkard’s hiccups give way to a young girl’s obscenities; where the triumph of French wit and gaiety consists in disguising as a soldier the most grotesque clown so that he may disgorge with his slobbering idiocy, the uniform for which our patriotic orators do their utmost, yet in vain, to demand respect. And then, you will arrive at the piece de resistance: a play or revue, whose title emblazons the posters with suggestive words and equivocal syllables, offering the public the irresistible attraction of lurid puns.” And it was this circus-like atmosphere that inspired Jean Cocteau to come up with a scenario entitled Parade that would almost certainly antagonize and offend the audience. “A Chinese magician, a little American girl and acrobats parade outside their tents giving free excerpts from their full performance in an effort to lure the audience into buying tickets. The crowd, however, mistakes their samples for the main show and disappears.”

To realize his vision of this multimedia spectacle and ballet, Cocteau assembled a unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time. Serge Diaghilev and the “Ballet Russes” commissioned and performed the piece, Léonide Massine provided the choreography, Pablo Picasso designed and painted the costumes and the set—including the red opening curtain, Guillaume Apollinaire wrote the program notes for the first performance and invoked the word “surrealism” for the first time, and the “enfant terrible” of the Parisian café-concert scene Eric Satie composed the music. Parade unfolds in seven sections entitled Chorale, Prelude of the Red Curtain, The Chinese Magician, The Little American Girl, Acrobats, Finale and Reprise of the Red Curtain Prelude. By relying on the vitalizing potential of the ‘everyday’ made visible in the appropriations of imported popular dances, Satie transformed Cocteau’s jumble of impressions into the most imposing piece of musical architecture. He placed the three central dance-numbers within a dual frame, that is, a twofold preliminary and a twofold conclusion. Each of the music hall numbers is framed with recurring entrance and exit music for the characters in question. Besides featuring a typewriter, pistol shot and sirens, the “Little American girl” dances a lugubrious ragtime. This dance mirrored the craze for American popular music that would soon reach a feverish peak with the appearance of American jazz ensembles in Europe around 1920. Furthermore Cocteau’s notion of American womanhood, which was inspired by Hollywood heroines like Mary Pickford and Pearl White, involved a high degree of athleticism, and unselfconscious sex appeal. “She swims, boxes, dances, and leaps onto moving trains,” Cocteau writes, “all without knowing that she is beautiful.” Maria Chabelska, who interpreted Satie’s ragtime music with great charm and gusto brought the dance to a poignant conclusion when, thinking herself a child at the seaside, ended up playing in the sand. Satie’s effort in composing music for the seven sections of Parade earned him the unflattering label, the composer for “typewriters and rattles.” The first performance of Parade in 1918 Paris was drowned in audience uproar, and the resulting journalistic battle resulted in a court case and a prison sentence for Satie, which typically, managed never to serve.

To realize his vision of this multimedia spectacle and ballet, Cocteau assembled a unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time. Serge Diaghilev and the “Ballet Russes” commissioned and performed the piece, Léonide Massine provided the choreography, Pablo Picasso designed and painted the costumes and the set—including the red opening curtain, Guillaume Apollinaire wrote the program notes for the first performance and invoked the word “surrealism” for the first time, and the “enfant terrible” of the Parisian café-concert scene Eric Satie composed the music. Parade unfolds in seven sections entitled Chorale, Prelude of the Red Curtain, The Chinese Magician, The Little American Girl, Acrobats, Finale and Reprise of the Red Curtain Prelude. By relying on the vitalizing potential of the ‘everyday’ made visible in the appropriations of imported popular dances, Satie transformed Cocteau’s jumble of impressions into the most imposing piece of musical architecture. He placed the three central dance-numbers within a dual frame, that is, a twofold preliminary and a twofold conclusion. Each of the music hall numbers is framed with recurring entrance and exit music for the characters in question. Besides featuring a typewriter, pistol shot and sirens, the “Little American girl” dances a lugubrious ragtime. This dance mirrored the craze for American popular music that would soon reach a feverish peak with the appearance of American jazz ensembles in Europe around 1920. Furthermore Cocteau’s notion of American womanhood, which was inspired by Hollywood heroines like Mary Pickford and Pearl White, involved a high degree of athleticism, and unselfconscious sex appeal. “She swims, boxes, dances, and leaps onto moving trains,” Cocteau writes, “all without knowing that she is beautiful.” Maria Chabelska, who interpreted Satie’s ragtime music with great charm and gusto brought the dance to a poignant conclusion when, thinking herself a child at the seaside, ended up playing in the sand. Satie’s effort in composing music for the seven sections of Parade earned him the unflattering label, the composer for “typewriters and rattles.” The first performance of Parade in 1918 Paris was drowned in audience uproar, and the resulting journalistic battle resulted in a court case and a prison sentence for Satie, which typically, managed never to serve.

Parade : Erik Satie Cocteau Picasso Diaghilev