The Greek legend of Orpheus—his descent to Hades and his fruitless attempt to bring his dead bride, Eurydice, back to the world of the living—is central to the emergence of opera. Orpheus was not only the legendary hero of Greek mythology but also the first superstar musician. Endowed with superhuman musical skills, he was nevertheless a flawed and arrogant mortal who sincerely believed that he could cheat death. On 5 October 1762, at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Christoph Willibald Gluck first introduced his musical setting of that famous story to the public.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orpheus and Eurydice, “Che farò senza Euridice”

Dual Settings

Orpheus and Euridice

Gluck’s setting premiered on Emperor Francis I’s name day with Empress Maria Theresa in the audience. It was a resounding success and went on to become the most popular of Gluck’s works. It proved to be highly influential in German opera as well, as variations on the plot, an underground rescue mission in which the hero must control or conceal his emotions, resurfaced in Mozart’s Magic Flute, Beethoven’s Fidelio, and Wagner’s Rheingold.

Ranieri de’ Calzabigi wrote the original libretto in Italian, but since Gluck made extensive use of accompanied recitative and shunned vocal virtuosity, the opera had a definite French flavour. Twelve years after the 1762 premiere, Gluck reworked the opera to suit the tastes of the Parisian public. He made several alterations in vocal casting and orchestration, and Pierre-Louis Moline provided the French libretto now titled Orphée et Eurydice.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice – Act I Scene 1: Aria: Chiamo il mio ben così (Jakub Józef Orliński, counter-tenor; Il Giardino d’Amore; Stefan Plewniak, cond.)

Reform Opera

Orpheus and Euridice

Gluck’s Orpheus is also significant because it is the first of his so-called “reform operas.” It ushered in a paradigm shift which replaced the operatic conventions of Metastasio. No longer concerned with da capo arias, castrati, or virtuoso singers, Gluck, to quote a commentator, “was serious about making opera serious.” The scholar Ernst Newman wrote, “Gluck focused on the dramatic interest of the recitative, on the lyrical portion being really lyrical, and on the importance of the chorus.”

Gluck unified the drama by blending together lyrical sections with recitatives and the choruses. Newman writes, “Gluck links each successive piece to its predecessor not, as formerly, by a mere juxtaposition, but causally, each dramatic moment growing out of that which preceded it.” Highly significant, the recitatives are now accompanied by the orchestra and no longer by the basso continuo.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orpheus and Eurydice, “Act II, Scene 2 Arioso: Che puro ciel ” (Júlia Hamari, contralto; Hungarian State Opera Chorus; Hungarian State Opera Orchestra; Ervin Lukács, cond.)

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orpheus and Eurydice, “Act II Scene 2: Torna, o bella, al tuo consorte” (Hungarian State Opera Chorus; Hungarian State Opera Orchestra; Ervin Lukács, cond.)

Tragic Beginning

“Orpheus and Eurydice”, Metropolitan Opera

A chorus of nymphs and shepherds join Orfeo around the tomb of his wife Euridice, who was bitten by a poisonous snake on her wedding day. As Orfeo sings of his inconsolable grief, Amor appears and tells him that he may go to the Underworld and return with his wife on the condition that he not look at her until they are back on earth. Amor tells him that his suffering will be short-lived, and Orfeo is ready to take on the quest.

The second Act is divided into two scenes, and the opening finds Orfeo confronted by the Furies; they refuse to admit him to the Underworld and threaten him with the hellhound Cerberus. However, when Orfeo accompanies himself on his lyre and begs for pity, the Furies eventually soften and let him in. Orfeo finds himself in Elysium and listens to a solo celebrating happiness in eternal bliss. He marvels at his beautiful surroundings but finds no solace as Euridice is not with him. He begs the spirits to bring her to him, and they oblige.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orpheus and Eurydice, “The Dance of the Furies

Happy Ending

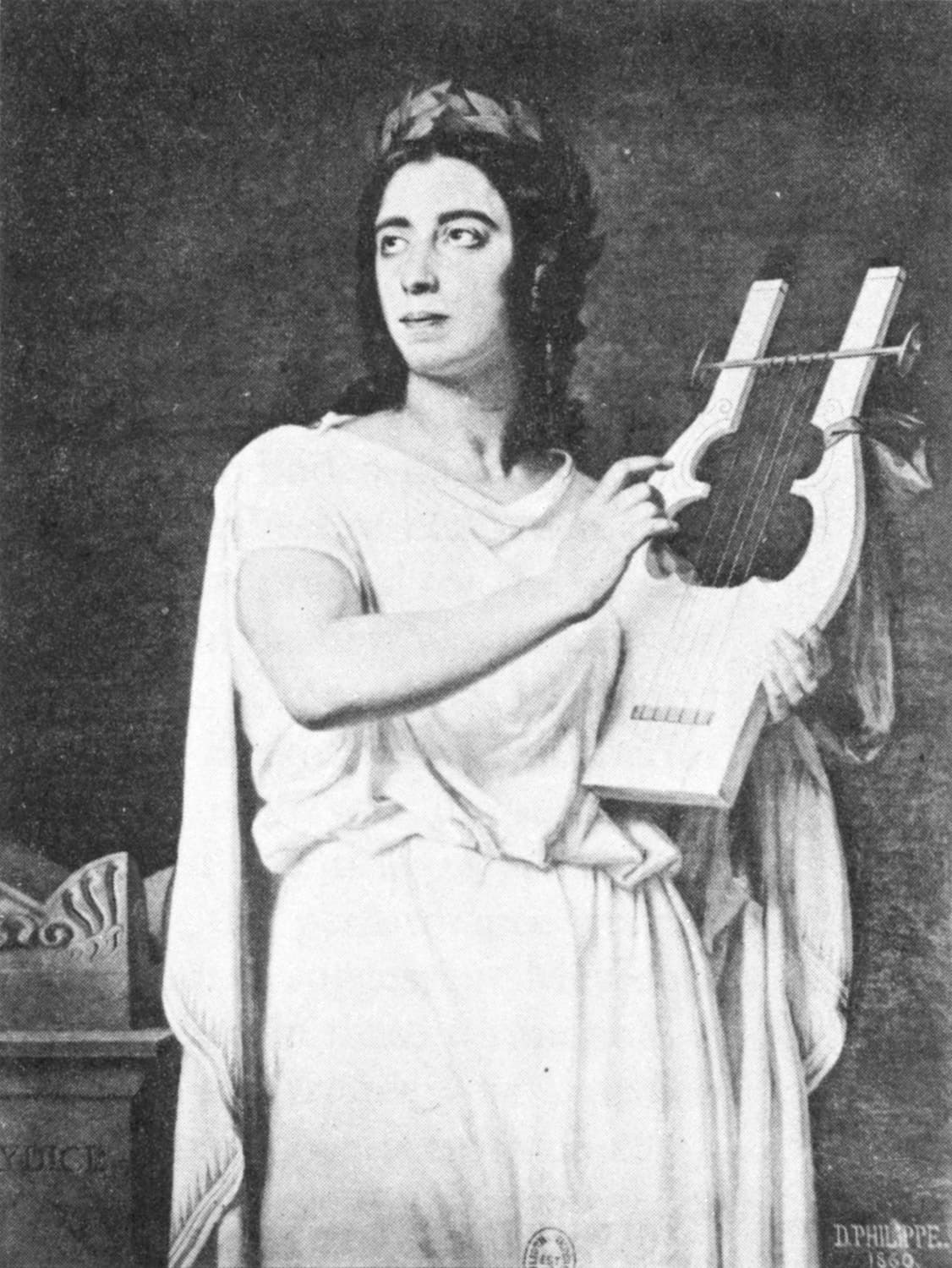

Pauline Viardot as Orphée, 1860

Orfeo is leading Euridice by the hand back to Earth, but when he refuses to look at her, she reproaches him. As Orfeo suffers in silence, Euridice believes he no longer loves her and concludes that death would be preferable. Overwhelmed, Orfeo turns to look at her, and she dies again. He decides to kill himself to join Euridice in the Underworld, but Amor stops him. Rewarding Orfeo’s continued love, Amor returns Euridice to life, and the couple is reunited with an unexpected happy ending.

Extended studies have been written detailing the differences between the Italian and French versions. Jeremy Hayes writes, “When Gluck made the French revision, some 12 years later, he was a much more experienced composer and man of the theatre, and the revision has an added sweep and grandeur.” Demoiselle Fabre, in Milan in 1813, made the first appearance of a female singer in the role of Orpheus, but the most famous female interpreter of the role in the 19th century was Pauline Viardot, for whom Berlioz prepared his 1859 edition.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter