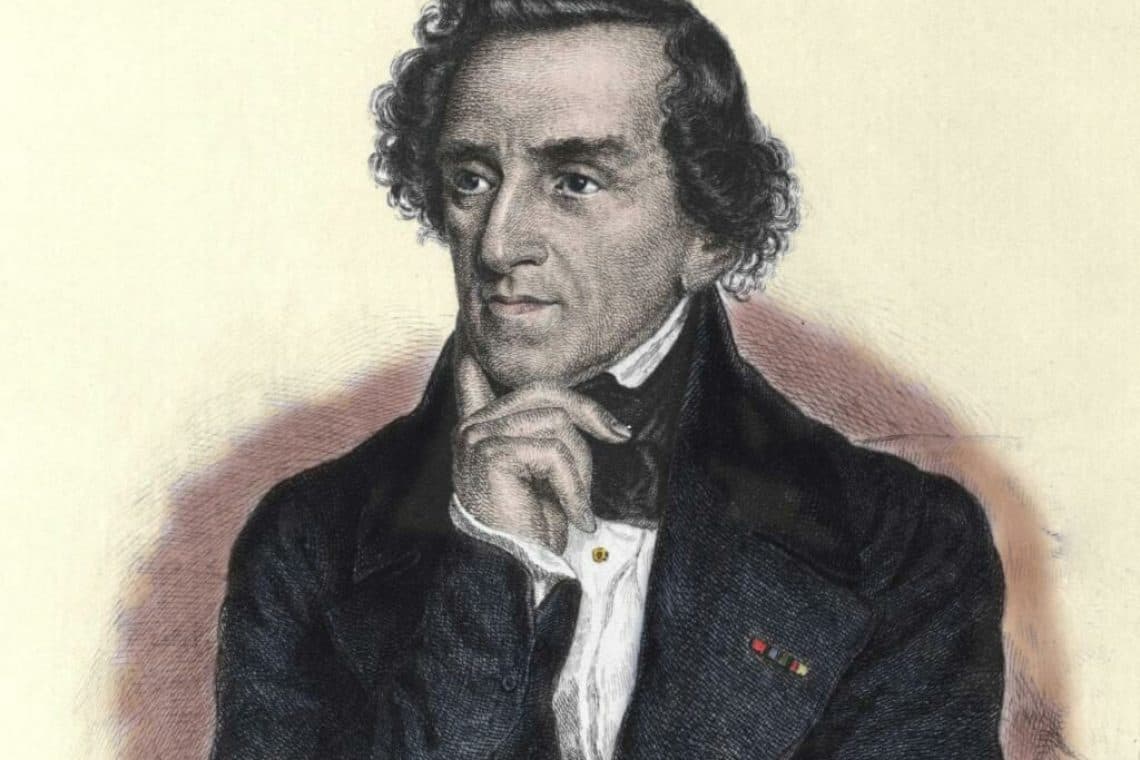

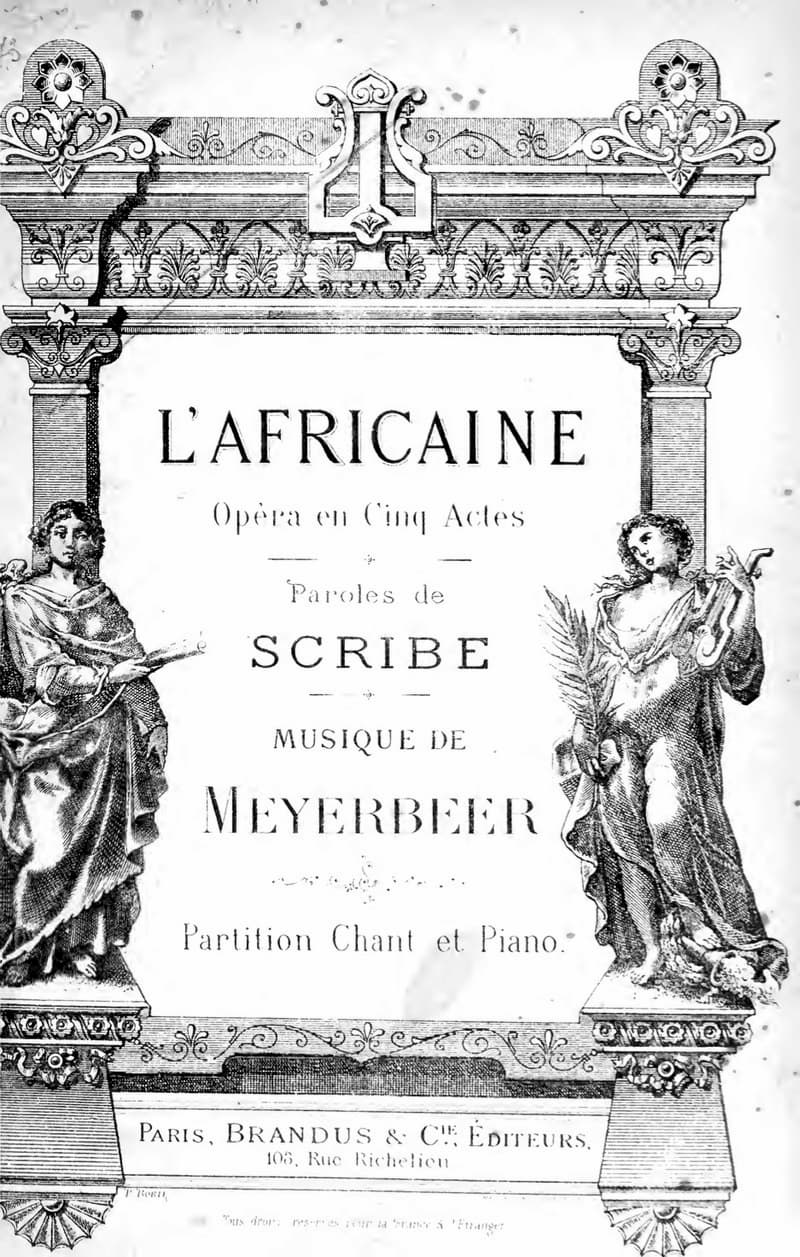

Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) had scored resounding triumphs with his two grand operas Robert le Diable and Les Huguenots. As a follow-up, he once again teamed up with the librettist Eugène Scribe for another project titled L’Africaine (The African Woman). The story originally tells of an African princess who has an unhappy romance with a Portuguese naval officer. When he decides to leave her for the woman he has loved for many years, she commits suicide by inhaling the poisonous fragrances of the manchineel tree.

Giacomo Meyerbeer: L’Africaine, “O Paradiso!”

A Difficult Process

Giacomo Meyerbeer

The opera premiered on 28 April 1865 at the Salle Le Peletier in Paris, almost thirty years after Meyerbeer and Scribe had begun working on the project. They had initially signed the contract in 1837, and the starting point was a poem by Charles Hubert Millevoye. In that story, the girl sits under a poisonous tree but is saved by her lover. Meyerbeer was decidedly unhappy with the libretto, and in the summer of 1838 he set the project aside to focus on preparations for Le Prophète.

Three years later, Meyerbeer resumed work, and he finished an initial draft and piano score for the first two acts in 1843. However, Meyerbeer was still unhappy with the libretto, and the original story set in Spain shifted to the Portuguese adventurer Vasco da Gama. That change of character brought with it a change of location, with Acts 1 and 2 now set in Lisbon and Acts 4 and 5 in India. Different projects once again intervened, and work only resumed in 1855.

Giacomo Meyerbeer: L’Africaine, “Ouverture” (Hannover Radio Philharmonic Orchestra; Michail Jurowski, cond.)

Meyerbeer’s Death

Eugène Scribe

Things got even more complicated when Eugène Scribe suddenly died in 1861. Since some of the text still needed to be written, he asked the German actress and author Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer to supply the texts. Meyerbeer wrote in his diary in November 1863, “Worked for seven hours; the last scene with Sélika instrumented and revised, and with it, the entire Vasco score concluded. Now only the overture and the ballet pieces and the possible changes remain. May God bless the work and lend it a brilliant and enduring success immediately on its appearance. Amen.”

Meyerbeer’s prayer sadly turned in a different direction. He continued to make minor revisions, but even before rehearsals could begin in earnest, the composer died on 2 May 1864. The composer had requested that the opera should not be given if he died before it was produced; however, his widow Minna Mayerbeer and the director of the Opéra engaged the Belgian musicologist François-Joseph Fétis to produce a performable version.

Giacomo Meyerbeer: L’Africaine, “Act III,” (excerpt)

The Premiere

Meyerbeer’s opera L’Africaine, cover of the piano vocal score

The premiere, shortly before the first anniversary of Meyerbeer’s death, was an enormous success. Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie attended opening night, and live reports of the event and its reception were telegraphed to other European capitals. At the conclusion of the performance, a bust of the composer, newly minted by Jean-Pierre Dantan, was unveiled on the stage. With everybody proclaiming the opera a masterpiece, it was quickly given in London and New York, and by 1866, it had reached Melbourne, Australia.

Paradoxically, binding together early nautical history, epic poetry, grand opera dramaturgy, ballet insertions, and a fictional account of Vasco da Gama’s first sea voyage to India, the work ushered the generic demise of French grand opera. Although L’Africaine stayed in the repertoire throughout the first half of the 20th century, audiences were no longer satisfied with great historicist tragedies as Wagnerism and Realism opened the way to the new “drame lyrique.”

Giacomo Meyerbeer: L’Africaine, “Fille des Rois”

François-Joseph Fétis

François-Joseph Fétis

Present-day commentators have taken Fétis to task for “toning-down Meyerbeer’s clear-minded examination of the complex relationship between colonial and sexual exploitation.

Fétis makes Sélika acquiescent by shortening or removing scenes in which she is assertive. And he prettifies her suicide, which Meyerbeer intended as troubling.”

To be sure, L’Africaine occupies a slippery position between eras and has baffled both scholars of French grand opera and critics of Orientalism. Cultural critique of opera’s involvement with the Orient as a sub-discipline of post-colonial studies has a relatively short history. As such, what we are left with is an opera that was completed by a contemporary of the composer. New critical editions have supplied all the published and unpublished parts as they existed before Fétis was invited to take over. How would “Vasco” have turned out if Meyerbeer himself had been present through the premiere? That’s a question that really does not have an answer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Giacomo Meyerbeer: L’Africaine (Bernhard Berchtold, tenor; Claudia Sorokina, soprano; Pierre-Yves Pruvot, bass; Guibee Yang, soprano; Kouta Räsänen, bass; Rolf Broman, bass; Anton Reimer, tenor; Martin Gabler, bass; Tiina Penttinen, mezzo-soprano; Tommaso Randazzo, tenor; Harald Meyer, tenor; Thomas Frob, tenor; Thomas Seidel, tenor; Bjorn Werner, bass; Stefan Kringel, bass; Chemnitz State Opera Chorus; Robert Schumann Philharmonie; Frank Beermann, cond.)