Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739-1799) was a highly respected violin virtuoso and prolific composer. It might be difficult to imagine today, but his popularity was said to have rivalled Haydn, Gluck, and Mozart. I think that might be a little strong, but according to some reports Dittersdorf played the first violin in private string quartet performances, with Haydn playing second violin, and Mozart the viola.

Portrait of Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf by Heinrich Eduard Wintter

The Irish tenor Michael Kelly saw and heard one such performance and wrote, “it was not outstanding, but the image of some of the greatest composers of their time joining in common music-making was unforgettable.” And as a composer, there is no denying, that Dittersdorf’s music is very original and full of the most beautiful ideas. In fact, he was a master of telling fanciful stories in music.

Dittersdorf was taught in a Jesuit school, and a secular priest was hired as his private tutor. As such, he had a thorough knowledge of the Latin language, unlike the majority of 18th-century musicians. It means that Dittersdorf “was capable of reading and interpreting Ovid’s Latin text of the Metamorphoses directly.” Let’s listen to two more of Dittersdorf’s fanciful stories in music, starting with “The Transformation of Acteon into a Stag,”

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 3 in G Major “The Transformation of Actaeon into a Stag” (Sinfonie: Allegro) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

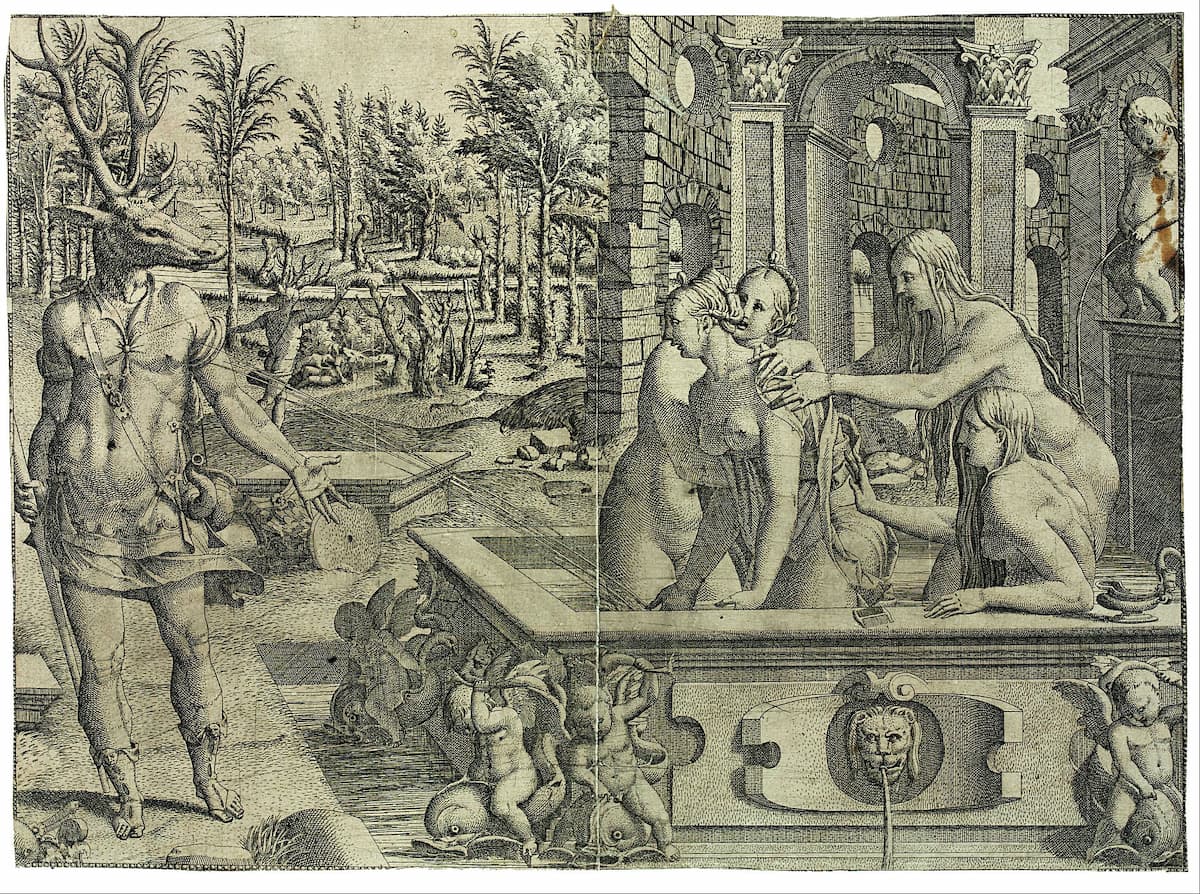

Jean Mignon: The Transformation of Actaeon

The story of the “Transformation of Actaeon” is a true metamorphosis. Actaeon was the son of the priestly herdsman Aristaeus and Autonoe, a Theban princess. Actaeon was an avid hunter, and with his comrades he wandered through the solitary wilds, “their spears and nets drenched with the blood of their victims.” And one day, he “wandered through out-of-the-way woods, as the young men ended their hunting.”

In the opening “Allegro” Dittersdorf immediately evokes a hunting scene with the horns engaging in ascending fanfares. The horns are heard throughout the movement, including the contrasting musical theme. But you can also hear that the music modulates to the minor key suggesting that all is not well. Especially in the development section, the opening horn calls take on a rather ominous character.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 3 in G Major “The Transformation of Actaeon into a Stag” (Adagio) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

This generic hunting scene is followed by a much gentler “Adagio,” with a flute solo warbling over the traditional figuration for murmuring streams and brooks. From the Ovid inscription, we learn that this is the valley of Gargaphie, dense with trees and sharp cypresses, where Diana, the goddess of the woods, tired from hunting, was taking a bath.

Dittersdorf provides a musical description of this enchanted place, which Ovid describes as “a wooded cave, not fashioned by art. But ingenious nature had imitated art. Nature had made a natural arch out of native pumice and porous tufa. On the right, a spring of bright clear water murmured into a widening pool, enclosed by grassy banks.”

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 3 in G Major “The Transformation of Actaeon into a Stag” (Tempo di minuetto) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

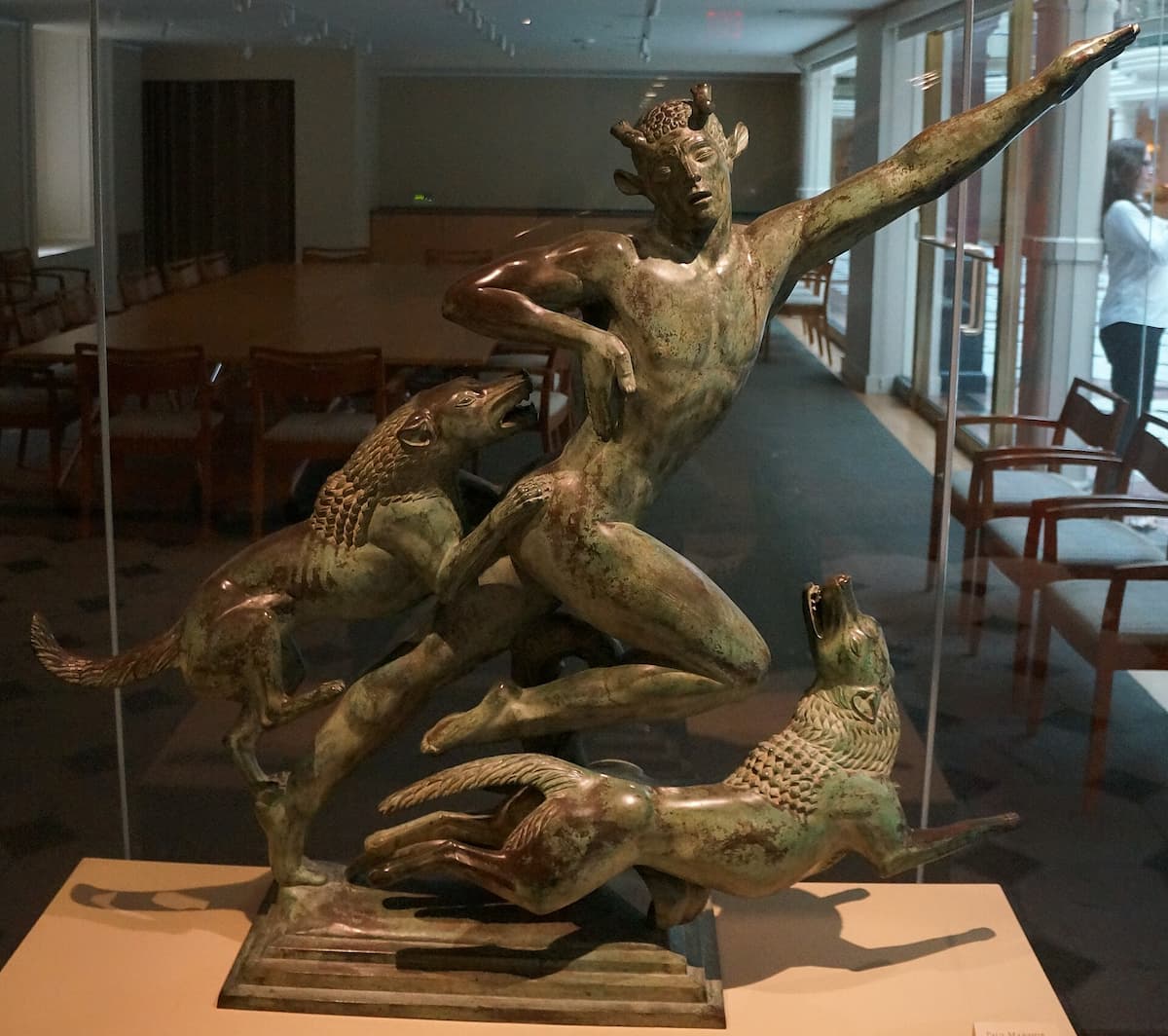

Diana and Actaeon Statues by Paul Manship

In the “Minuet,” we are finally introduced to an awestruck Actaeon, who accidentally wanders into the cove. As he stares in amazement at Diana’s ravishing beauty, all the nymphs, in great confusion, try to hide naked Diana with their bodies, but “the goddess stood head and shoulders above all the other.” Diana was certainly not amused and told him, “now you may tell, if you can tell, of having seen me naked.” And to make sure that he would not tell, she turned him into a stag.

Initially, Actaeon is rather amazed at the speed at which he travels through the forest, but then he sees his head and horns reflected in the water. But things turn really grim when he realises that his own dogs are now pursuing him. Actaeon runs over the place where he has often hunted, now chased by his own dogs. He shouts, “I am Actaeon! Know your own master,” but words fail him. In the end, he is torn apart by his own dogs. Dittersdorf’s music provides us with that breathless chase, including the barking of the dogs. Once the deed is down, the music gradually subsides as this fanciful story comes to a sombre end.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 3 in G Major “The Transformation of Actaeon into a Stag” (Finale: Vivace) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

Perseus rescues Andromeda

Scholars and musicologists have suggested that “Dittersdorf’s response to Ovid’s poem was primarily visual, in the form of imaginary pictures, before it was musical as the composer initially planned to publish the symphonies with attached engravings.” In keeping with the Classical ideal, the composer presents us with discrete musical pictured, essentially depicting action sequences.

In this way, Dittersdorf replaces the impossible challenge of recreating Ovid’s complex narrative style in music with his own innovations in the style and form of the Classical symphony, “which permit sound to function as image, or, at least, as the inspiration for imagination.”

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 4 in F Major “The Rescuing of Andromeda by Perseus” (Adagio non molto) (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Kehr, cond.)

In Dittersdorf’s fourth fanciful story, the composer tells us about Perseus, one of the greatest heroes of Greek Mythology. He is the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Danae, and he is probably best known for slaying Medusa. She was a monster described as a winged human female with living venomous snakes in place of hair, and those who gazed upon her face would instantly turn to stone. Well, Perseus had none of it and simply chopped off her head by looking at Medusa’s reflection in a mirror.

Dittersdorf’s Symphony in F Major is scored for pairs of oboes, horns, and strings. The opening “Adagio” does not feature an Ovid inscription, but from the story, we know that Perseus had just used the head of Medusa to turn Atlas into stone, turning this Titan into a mountain. The music paints the picture of Perseus strapping on his winged sandals and flying through the sky, with the solo oboe soaring over muted strings.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 4 in F Major “The Rescuing of Andromeda by Perseus” (Presto) (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Kehr, cond.)

Titian: Perseus and Andromeda

In the ensuing “Presto,” we find Perseus flying high over the kingdom of Ethiopia and spotting the beautiful and helpless maiden Andromeda, chained to the rocks, waiting to be devoured by a sea monster. Andromeda was the daughter of King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia, and one day Cassiopeia bragged that her daughter was more beautiful than the sea nymphs.

Poseidon, the god of the sea, became furious at such a boastful statement and unleashed the sea monster Cetus. In the end, it was suggested that the only way to appease Poseidon was to sacrifice Andromeda. In his composition Dittersdorf is musically reacting to this gloomy story by sounding a doleful lament in a beautiful and emotional “Larghetto.”

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 4 in F Major “The Rescuing of Andromeda by Perseus” (Larghetto) (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Kehr, cond.)

As you might have guessed from the subtitle of this symphony, when Perseus finds Andromeda helplessly on the rock shore he immediately falls in love with her. And since he is a hero, he quickly kills the monster Cetus. There is great rejoicing as Perseus marries Andromeda, and their children founded the Persian nation and people. Even Zeus was very pleased, which was rather unusual for him.

The concluding “Finale” does start in the minor key to give us a sense of the turbulent great battle, but it soon moves towards a “tempo di minuetto” in the major key to celebrate the happy occasion. I think these fanciful stories in music should be performed much more frequently, as Dittersdorf creatively adapted the formal structures of a common Classical symphony to tell these wonderful stories.

I hope you can join us for the two concluding fanciful stories in music when Dittersdorf tackles the “Transformation of Lycian peasants into frogs” and musically turns “Phineus and his friends into stone.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 4 in F Major “The Rescuing of Andromeda by Perseus” (Finale: Vivace) (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Kehr, cond.)