During the final years of his life, Giuseppe Verdi devoted himself to a number of philanthropic ventures. Chiefly among them was the establishment of a hospital at Villanova sull’Arda, close to Busseto.

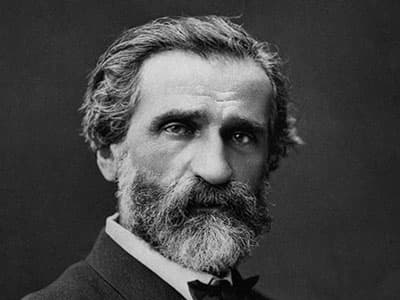

Giuseppe Verdi

Yet, overseeing such a noble cause was not an easy task. As he writes, “I think it right to warn you that I have had bad reports about the hospital and I hope and pray they are not true… I am far away and can say nothing about this (mismanagement). But in any case, I am extremely distressed and it makes me wonder if I can achieve the purpose for which I devoted part of my fortune in endowing this charitable foundation.” Verdi also donated some royalties to the victims of a major earthquake in Sicily, and beginning in 1895, he built and endowed a rest home for retired musicians in Milan, the “Casa di Riposo per Musicisti.”

Giuseppe Verdi: Four Sacred Pieces

Verdi’s Health Issue Before His Wife’s Death

Giuseppina Strepponi, 1897

In January 1898, Verdi experienced a major health scare. One day, his second wife Giuseppina Strepponi found him paralyzed in bed and unable to speak. While deciding if a doctor should be called, Verdi motioned for pen and paper. In a very shaky script, he wrote “Coffee,” which was brought to him. Yet, within a couple of days, Verdi had fully recovered. Somewhat surprisingly, the death in the family later that year was not his, but Giuseppina’s. She had been suffering from severe arthritis and was unable to walk without help. Bronchitis set in in November, and she died a couple of days later. The family lawyer remembered, “Verdi standing at the piano, his head bowed, his cheeks flushed, the picture of silent grief.” The funeral service was held in Busseto Cathedral, and Verdi spent lonely weeks at S. Agate. As he wrote to a friend, “Great sorrow does not demand great expression; it asks for silence, isolation, I would even say the torture of reflection.”

Giuseppe Verdi: Otello, “Ave Maria, piena di grazia”

Verdi’s Last Days in Milan

Giuseppina Pasqua, Teresa Stolz, Giuseppe Verdi, and Leopoldo Mugnone

Verdi was spending more and more time in Milan at the Albergo Milano, close to his friends Arrigo Boito, Giulio Ricordi, and Teresa Stolz. He entertained a number of visitors, including journalists, writers, and musicians. Verdi was keenly interested in the musical life of the city, and “he approved of the fact that operas were much shorter than they used to be and that there was no longer any need to think up some chorus or other to fill out the scene.”

1900 group portrait at Verdi’s house in Sant’Agata with family and friends, including Verdi (middle), Giulio Ricordi (second from the right) and Teresa Stolz (left)

Toscanini visited him on 20 January 1901 but found Verdi somewhat confused. The very next day Verdi suffered a stroke, and growing weaker by the day, he died at 3 a.m. on 27 January 1901. His librettist and poet Boito wrote, “He died magnificently, like a fighter, redoubtable and mute… The breathing of his great chest sustained him for four days and three nights; on the fourth night the sound of his breathing still filled the room, but what a struggle. How magnificently he fought up to the last moment. I have never experienced such a feeling of hate against death, such loathing for its mysterious, blind, stupid, triumphant infamous power!”

Giuseppe Verdi: Falstaff (Excerpts)

The Funeral Service

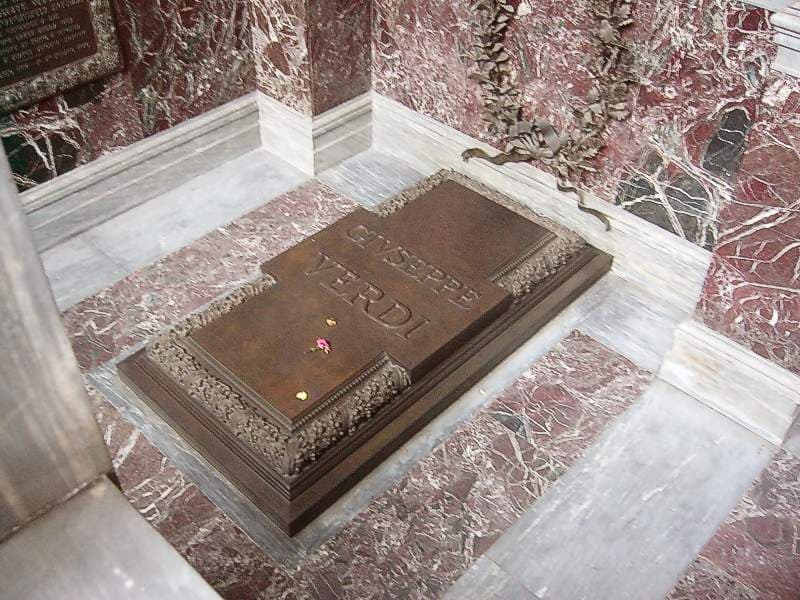

Verdi’s grave at Casa di Riposa, Milan

The initial funeral service took place in a private ceremony at the Cimitero Monumentale in Milan. A month later, his body was moved to the crypt of the Casa di Riposo, and placed next to Giuseppina. In her will, she had written, “Now, addio, my Verdi. As we were united in life, may God rejoin our spirits in Heaven.” Boito wrote, “In the ideal, moral, and social sense, Verdi was a great Christian. But one must be very careful not to present him as a Catholic in the political and strictly theological sense of the word; nothing could be further than the truth.” An estimated 300,000 people lined the streets and Arturo Toscanini with a chorus of 820 singers, conducted “Va, pensiero” from Nabucco.

Boito wrote to a friend, “Verdi now sleeps like a King of Spain in his Escurial, under a bronze slab that completely covers him.” By the time Verdi wrote his last operas, he had become a national monument, and “the premières of Otello and Falstaff were cultural events of almost unprecedented importance.” However, the operatic times had changed, and in the increasingly sophisticated, cosmopolitan atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Italy, Verdi’s musical personality was too simple and direct, and Wagner and the Italian veristi were making the headlines instead.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco, “Va, Pensiero”