The exceptional and brilliant violinist Henryk Wieniawski, born on 10 July 1835 in Lublin, was quickly considered a reincarnation of Nicolò Paganini. In the summer of 1848, a German reviewer writes, “Our third guest, violinist Wieniawski, is a 12-year-old boy who received the first prize in the Paris Conservatory. In any case, he is possessed of a true talent, deserving our attention. His technical capabilities are highly advanced; his strong and bold bowing technique is particularly vivid in staccato; and his intonation is mostly excellent. More notable than these traits is the fact that these technical capabilities, though easy to perceive in and by themselves, are presented in interpretations filled with good taste, at times even spiced up with intensity and permeated with the impetuous passion that seems to indicate a true genius.” And the review continues, “I have to mention here his own compositions, some of which were heard here, mostly with the accompaniment of an orchestra. These works also testify to his extraordinary, well-developed talent.”

Henryk Wieniawski: Allegro de Sonate, Op. 2

Franz Liszt was suspicious, however, as he considered virtuosity, not a “display or trick, but a level of integral characteristics of a compositions style.” As such, Liszt subsequently wrote in a letter to Franz Brendel of 1853, Wieniawski’s playing is not of “true virtuosity.”

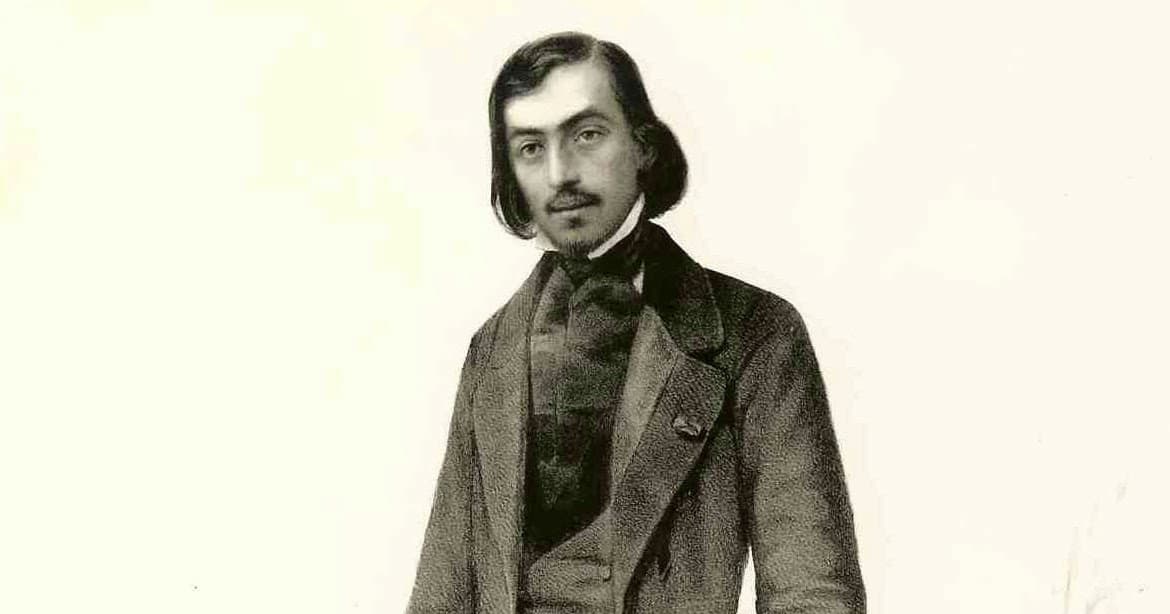

Henryk Wieniawski

However, let’s start at the beginning. Henryk’s father, Tadeusz, was a learned man who operated an extensive medical practice. He was politically active, and openly opposed the Russian invasion of his country. His mother, Regina Wieniawska (née Wolff), was a professionally trained pianist, who had studied piano in Paris, and the sister of the noted pianist Eduard Wolff. As a biographer writes, “she brought her musical interests into the family home, and music became an integral part of the upbringing of the Wieniawski children. It has been said that Regina held a particular admiration for the music of Chopin, and that many distinguished violinists visited Mme Regina’s salon.” As such, it might come as no surprise that Henryk was immediately drawn to the violin. In the event, it is beyond doubt that Regina was “the driving force behind his musical training and subsequent development into a violin child prodigy.”

Henryk Wieniawski: Souvenir de Posen, Op. 3

Wieniawski’s exceptional talent for the violin was quickly recognized, and at the age of five, he received his first lessons from Jan Hornziel. He had been a former student of Louis Spohr, and when he left Lublin, Henryk continued his studies with Stanisław Serwaczyński, who had previously instructed Joseph Joachim.

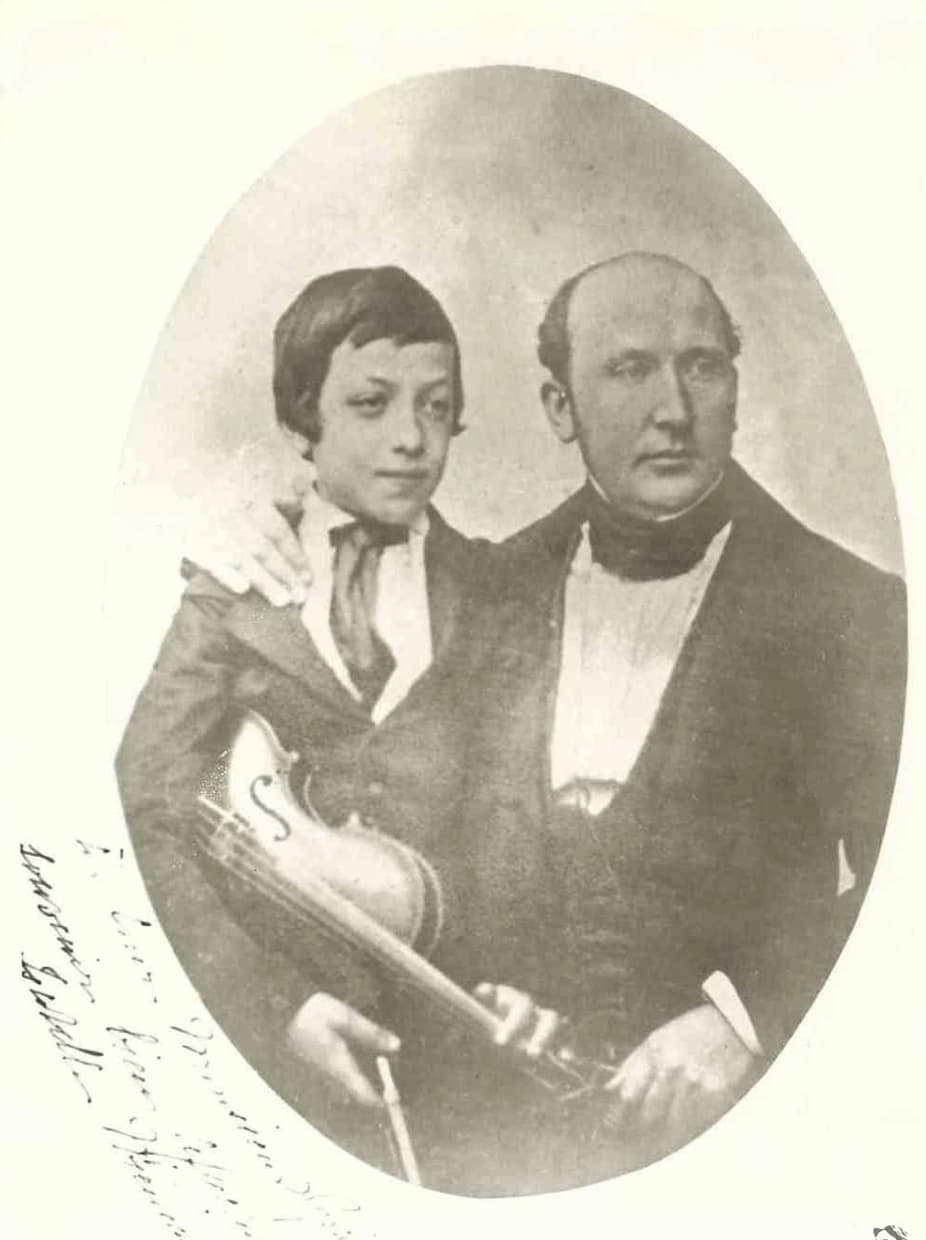

Teenage Henryk Wieniawski with his teacher Lambert Massart © Wieniawski Music Society

Henryk made exceptional progress and gave his first solo public appearance at the age of seven. An amusing anecdote tells that when the Czech violinist Panofka visited Warsaw and heard the eight-year-old boy play, he supposedly exclaimed, “He will make a name for himself.” His mother quickly decided that Henryk should continue his studies in France, and in the autumn of 1843, the eight-year old boy and his mother arrived in Paris. After playing a “brilliant audition for the Paris Conservatoire, Henryk was admitted to the class of J. Clavel and transferred to the master class of Lambert Massart a year later.”

Henryk Wieniawski: Grand caprice fantasique, Op. 1 (Jacques Israelievitch, violin; Stéphane Lemelin, piano)

Stanisław Serwaczyński

Henryk quickly became known as “Le petit Polonais,” and after two years of study, the Director of the Conservatoire, Daniel Auber, wrote a special report signed by the other teachers. “Our highest hopes in Mr. Massart’s special violin class rest in young Wieniawski, aged 10 years and 4 months.” True to Auber’s prediction, Wieniawski was awarded the first prize in violin in 1846 and continued to study privately with Massart for an additional two years. He performed a highly successful recital with his young brother Józef Wieniawski at the piano on 30 January 1848 and subsequently departed for St Petersburg. There he gave at least five successful performances and took part in various music meetings in private salons of musicians and art patrons. He earned the praise of Vieuxtemps, who at that time was solo violinist at court. Already at that time, Wieniawski’s playing was described as “graceful, charming, spirited, and with extraordinary energy in variations, caprices, and concertos.” However, it was also written that he never played chamber music well. “Wieniawski would often get carried away with a phrase or passage. He would launch scintillating fireworks of virtuosity, if you will, but totally out of place, with no regard otherwise for what his partners were doing.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter