It is the fall of 1871. A twenty-six-year-old Ukrainian woman sends a cable to Europe to pianist and composer Franz Liszt. She warns him that she is about to cross the ocean to kill him. Ten days later, she shows up at his doorstep.

Outrageous as it sounds, this story is actually true. Today we’re looking at the life of pianist and novelist Olga Janina, whose relationship with Liszt nearly killed him.

Olga Janina’s Childhood and Marriage

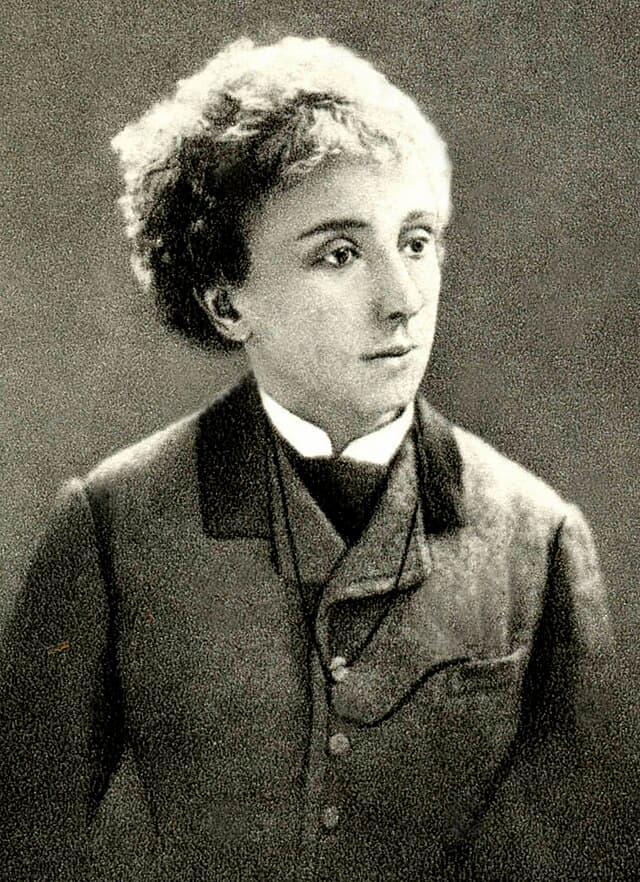

Olga Janina

Olga Janina was born Olga Zelińska on 17 May 1845 in present-day Lviv, Ukraine, the daughter of Ludwik Zieliński and Lopuszanska Sabina. The family was musical: her mother was a pianist, and her older brother was Jarosław Zieliński, a pianist, composer, teacher, and music critic. She began studying piano with her mother when she was a little girl.

Her family was relatively wealthy. Her father had made money inventing and selling a new formula of boot polish. In fact, in the mid-1850s, her family hired a Czech composer named Vilém Blodek to serve as her private tutor.

In 1863, the year she turned 18, she married a nobleman named Karol Janina Piasecki. They had one daughter, Helene, but the marriage didn’t last long.

She would later write a fictionalized account of her life in which, in revenge for his wedding night cruelty, she horsewhipped her husband and left him the following day.

In the end, the only thing she kept of her husband was his second name, which she turned into her professional surname.

Meeting Liszt

After her marriage broke down, Janina began ping-ponging around Europe, taking music lessons from various teachers.

In April 1865, she went with her mother to Paris to study under Henri Herz and made her public debut. In 1866, she went back to Lviv to study with a Polish pianist named Karol Mikuli, a Chopin student.

Then, fatefully, in 1869, she went to Rome to study with Franz Liszt. She’d heard him play in April in Vienna, and she was absolutely entranced. She arrived in May. Liszt was surprised when he met her: she’d signed her name “O. Janina”, and he’d been expecting a man.

Janina cut a dashing figure. She smoked cigars, wore men’s clothes, carried a dagger with a poisoned tip, wielded a revolver, smoked a great deal of opium and laudanum, and declared (falsely) that she was a Cossack countess. She approached her music-making with unnerving intensity: she was known for biting her nails down so far that she left blood on keyboards.

German historian Ferdinand Gregorovius reported of her in October 1869 that she was “a little, witty, foolish person, mad about Liszt.”

Franz Liszt: Mosonyis Grabgeleit, S.194

Liszt’s Mosonyis Grabgeleit, S.194, from 1870, around the time he was teaching Janina.

A Love Affair with Liszt?

It is possible that Liszt and Janina embarked on some kind of romantic relationship during this time. Years later, in a fictionalized account, she claimed that he told her, “I can resist you no longer!” and that they went to bed together. It’s unclear whether this fictionalized version of their relationship had any truth to it.

Despite her eccentricities, or maybe because of them, Liszt was impressed by her talent.

In 1870, he invited her to perform at the Weimar Festival in Weimar. She worked as a copyist for him, and he encouraged her to learn his piano concertos.

Yuja Wang: Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, S.124

A Break in the Liszt Relationship

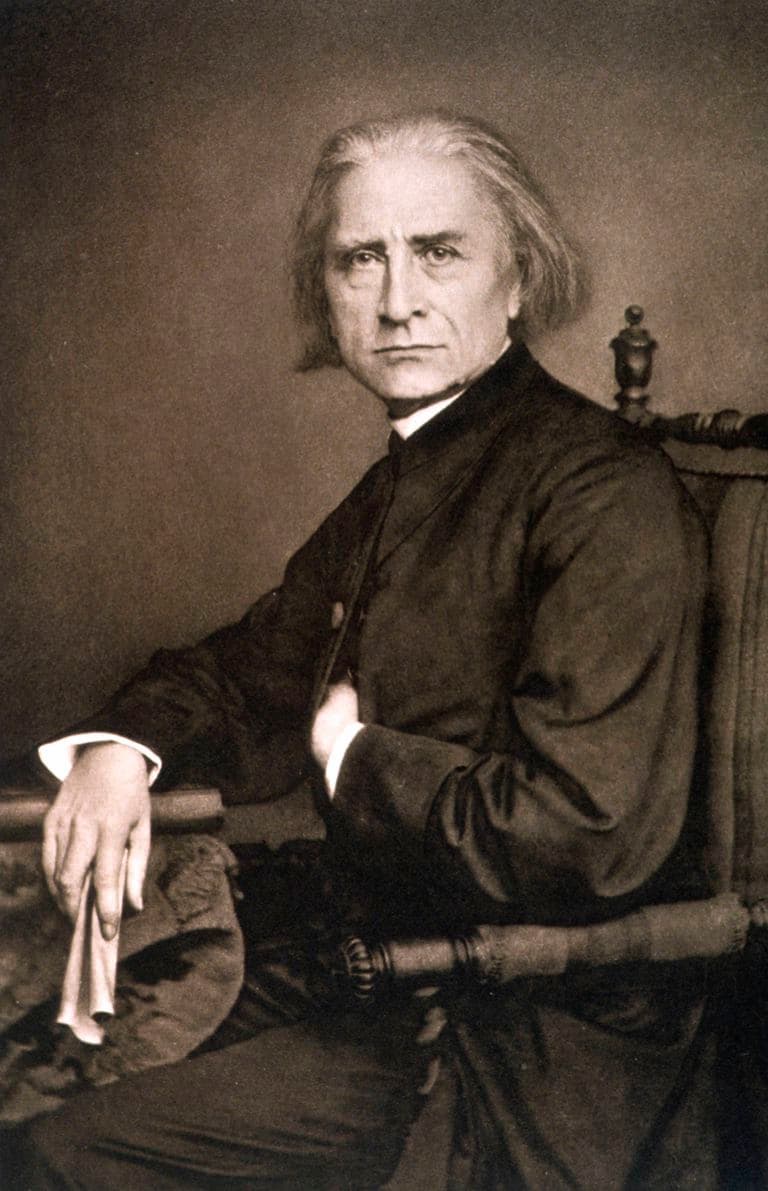

Franz Liszt in 1870

During the winter of 1870-71, Liszt invited Janina to remain in his entourage while he spent the winter in the city of Pest.

While there, she had a horrifying memory lapse that would prove consequential to her relationship with Liszt.

Hungarian authoress Janka Wohl described the scene at a private concert:

When her turn came she was very graciously received, and she commenced her [Chopin] Ballade, of course playing by heart. All went well until the sixth page, when she hesitates and gets confused. In desperation she begins again, encouraged by indulgent applause. But, at the very same passage, her overwrought nerves betray her again. Pale as a sheet she rises. Then the master, thoroughly irritated, stamps his foot, and calls out from where he is sitting: “Stop where you are!” She sits down again, and, in the midst of a sickening silence, she begins the wretched piece for the third time. Again her obstinate memory deserts her. She makes a desperate effort to remember the final passages, and at last finishes the fatal piece with a clatter of awful discords.

I was never present at a more painful scene. Going out, the master upbraided her more than angrily, as she clung to his arm. He had been severely tried, and he at last lost all patience with the freaks of his pupil. And, this breakdown confirming as it did, his oft-expressed opinion that she was not of the stuff that artists are made of, he no longer spared her.

In the spring of 1871, Liszt confided in a letter to his partner, author Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, that the radical ideas of George Sand “[seem] faint and timid to [Janina]” and that she had attempted suicide several times. However, he begged Carolyne not to share a word of his student’s troubles.

Plotting Her Revenge

Olga Janina

Around this time, Janina’s father died, creating new financial and emotional pressures.

After an ill-fated gambling trip to Baden-Baden with her brother, she crisscrossed the world, trying to establish herself as a concert pianist. She started out by touring Russia and then moving to America.

Liszt had encouraged her to move overseas. He entrusted her with the three-volume manuscript of his Technical Studies to bring to a publisher named Julius Schuberth. The request made a certain amount of sense, as he’d trusted her to work on a fair copy back in Rome. Schuberth had promised to give her $1000 for the manuscript, the rough equivalent of $25,000 today. Unfortunately, somehow, she lost the manuscript and kept the thousand dollars.

Franz Liszt: Technical Studies, S.146 (Schuberth’s edition)

A modern MIDI transcription of Liszt’s Technical Studies.

Trying to Murder Liszt

On 15 October 1871, she cabled Liszt that she was coming back to Europe to kill him. Ten days later, she followed through, showing up at his door with her famous revolver and a variety of dangerous drugs.

Liszt spent hours talking to her, and later, two of his friends joined, too. She insisted that the only object she had in life was to murder Liszt and then die by suicide.

Liszt thought about contacting the police during the crisis, but he felt that they wouldn’t get there in time to make a difference.

She ended their discussion by taking poison and going into convulsions. Liszt returned her to her hotel, and a doctor was called. Turns out, the poison hadn’t been poison at all, and she presumably was faking her reaction.

Liszt’s friends relayed firm conditions: she was to leave Budapest immediately or be prosecuted.

The event shook Liszt up badly. He explained the situation in vague terms in a letter to Carolyne, and wrote, “I wish to forget this episode as soon as possible which, thanks to my guardian angel, did not end in catastrophe or in a public scandal.”

Plotting Additional Revenge…With Steamy Novels

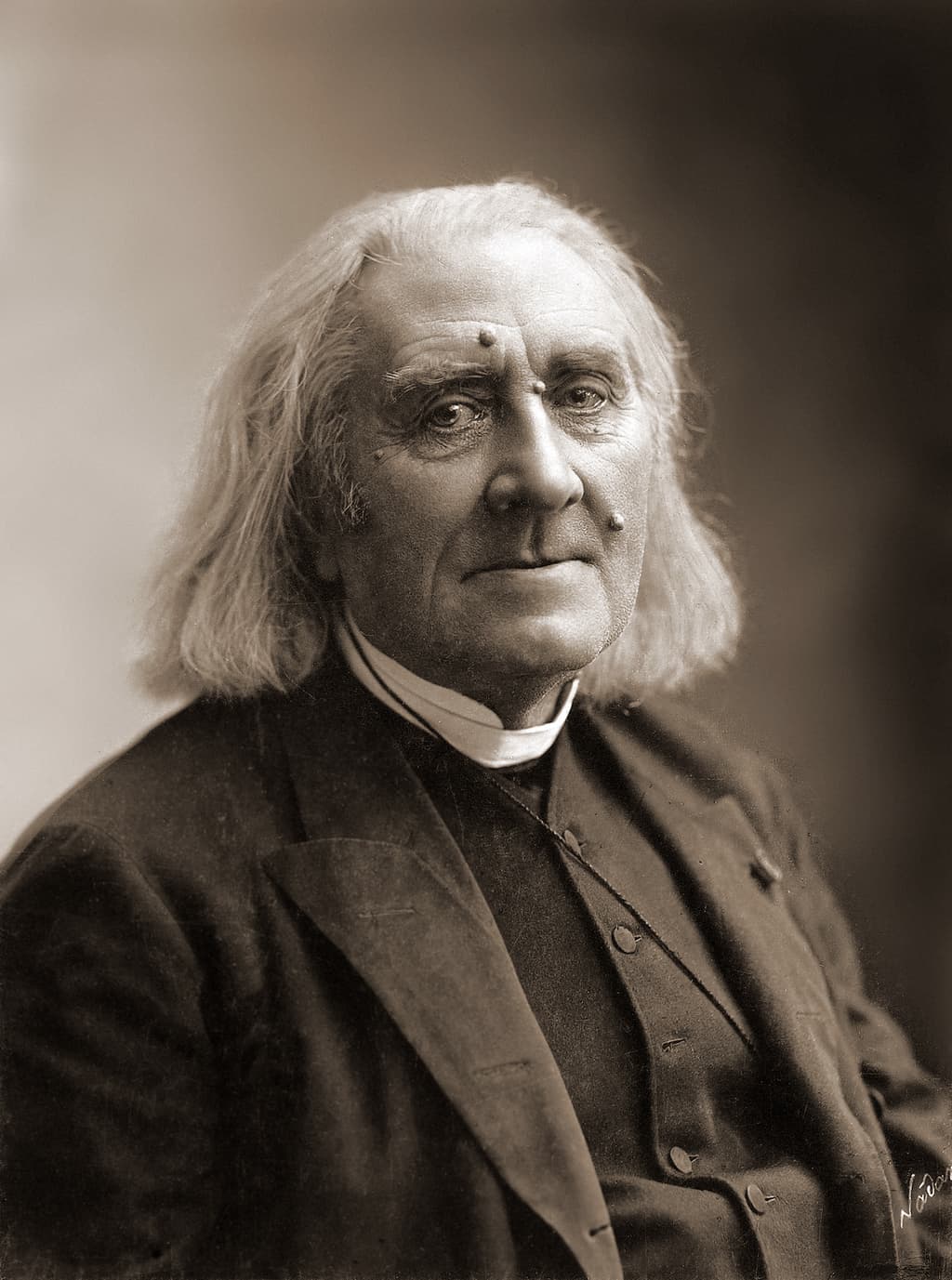

Franz Liszt in 1886

Janina then took her weapons and her drugs and moved to Paris, where she performed Liszt’s works and gave lectures about him. She also began to write fiction.

In 1874, she published a novel under the pseudonym Robert Franz. (She had clearly chosen the name to insult a Liszt friend and confidant, composer Robert Franz Julius Knauth.) She titled her novel Memories of a Cossack.

The book is about a composer/abbot named Abbot X and his steamy love affair with a student. It was a thinly veiled reference to Liszt, who had become an abbé in 1865.

The same year, she wrote another novel from the perspective of what she imagined Liszt’s response to her first book would be. She published it anonymously and called that one Memories of a Pianist.

Two novels however, were not enough. So she created the persona of Sylvia Zorelli, purportedly a friend of the protagonist of the first two books, and wrote two more novels from Sylvia’s perspective: The Loves of a Cossack, by a friend of Abbot “X”, and The Romance of the Pianist and the Cossack.

She returned to her Robert Franz persona in 1876 to write Letters from an Eccentric.

In the process, Janina created a whole backstory for her fictional self. One of the most shocking stories was that she owned a tiger in Ukraine and that the Kiev Conservatory had to shut down after it attacked one of the school’s leaders. Readers understood that parts of her story were true and other parts fabricated, but it was never clear which were what.

She capped her novel-writing career off by sending copies of the books to Liszt’s famous friends…and the pope.

What Was Liszt’s Response?

So how many of the events in these novels actually happened? Historians aren’t sure, so it seems like we’ll have to be content not knowing.

What did Liszt think of Janina? There must have been something remarkable about her, because despite her ferocious one-woman PR campaign against him, he never blamed her for her behavior, feeling that she didn’t have full control over herself. “And in my opinion, she was talented,” he said.

Olga Janina’s Later Life

In 1881, Janina married writer Paul Cézano. She created a home base in the town of Lancy, Switzerland, and through the early 1880s, traveled Europe giving performances. She remade her identity yet again, performing now as Russian pianist Olga Lvovna Cézano.

In 1886, she co-founded the Geneva Music Academy in Geneva, Switzerland. She only stuck around for a year, founding a Higher School of Piano and Harmony soon afterward.

Cézano died in 1887. She remarried a professor and gynecologist named François Vulliet.

She kept performing even after her marriages, and scattered reviews of her appearances have survived. In London, a critic called her “a performer of average caliber at best, although rumored to have a strong reputation on the Continent.” Reviews were more positive in Paris in 1894, where she gave a concert of Brahms’s works a few years before he died.

Her third husband Vulliet died in 1896. She moved to the south of France for a while before returning to Paris, where she died on 13 July 1914, a few weeks before the start of World War I. True to chaotic form, she had embraced one last pseudonym: the one-word “Nikto.”

Janina’s Legacy

Olga Janina has been largely forgotten by music lovers. When she’s remembered, it’s usually as being an eccentric, mentally unstable harlot.

But there’s an element of sexism at play there. Hector Berlioz, for instance, came up with a murder-suicide plot very similar to Janina’s, coming close to killing his pianist fiancée for marrying another man, and yet we still listen to his Symphonie Fantastique regularly. Indeed, we even celebrate it.

One thing is clear: despite whatever mental health troubles she struggled with, Olga Janina was someone who Liszt (at one point, at least) valued and admired and maybe even loved. Her story is worth remembering.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Element of sexism? How? I would avoid assigning modern sobriquets to members of a culture two hundred years away (Berlioz).

The article is excellent and fascinating, however