The invention of the Gutenberg press set in motion a musical and societal revolution. For one, the demand for music as entertainment and as a social activity for educated amateurs increased with the emergence of a bourgeois class. From this changing society emerged a common and unifying musical language that could now be disseminated throughout Europe. This unification of polyphonic practices into a fluid style culminated in the second half of the 16th century in the works of composers such as William Byrd, Lassus and Palestrina. And it was polyphonic vocal music, in both a sacred and secular context, that dominated the musical landscape. Canons and Rounds had long been part of the musical narrative, and entire mass settings were based on intricate and highly sophisticated canonic plans.

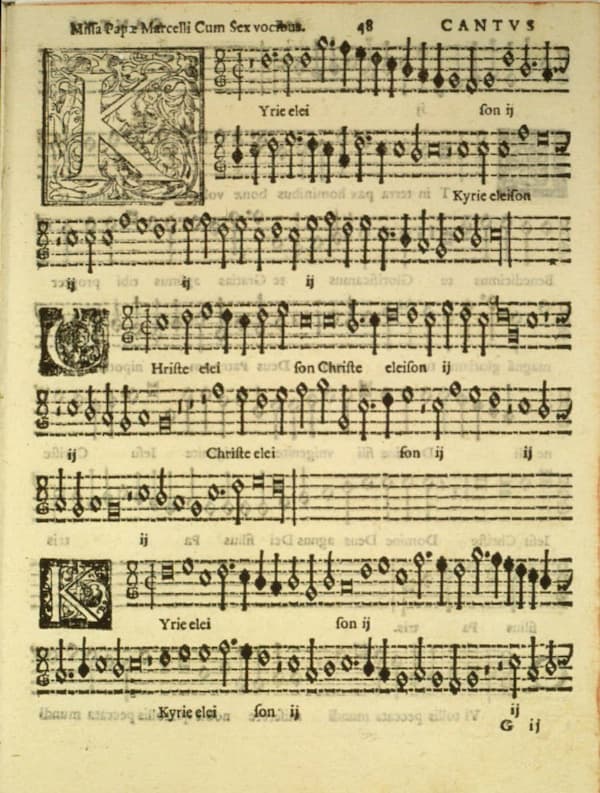

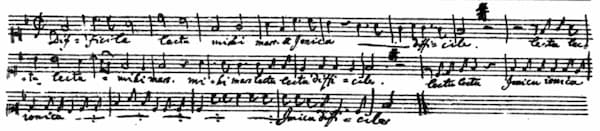

Palestrina’s Mass, 1597

Based on a motet by Jachet de Mantua, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina composed his “Missa Repleatur os meum” for 5 voices in 1570. With only a couple of exceptions, the mass features canons between the Tenor and Quintus throughout. It all starts with a canon at the octaves, 8 beats apart. From then on, the canons decrease in intervals and time until a canon at the unison and beginning 1 beat apart is reached in the final section of the mass setting.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: Missa Repleatur os meum, “Kyrie I” (Delitiæ Musicæ; Marco Longhini, cond.)

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: Missa Repleatur os meum, “Kyrie II” (Delitiæ Musicæ; Marco Longhini, cond.)

Mozart’s Canon “Difficile lectu”

I could certainly listen to Renaissance canonic wizardry forever, but not all of my favorite canons are of such a serious kind. In fact, they can be downright bawdy. In 1799 Constanze Mozart sent some manuscripts of her late husband to the Leipzig publishers Breitkopf & Härtel. One particular manuscript contained canons by Wolfie Mozart, which he had probably written in Vienna in 1782. In her accompanying letter, Constanze implied that some of the canons would need to be adapted before they could be published. Probably, Costanze was talking about the six-voice canon in B-flat major, K. 231, which was then published with the words “Laßt froh uns sein” (Let us be glad). The original text for that canon was discovered only in 1991. Researcher at Harvard University found the matching text in the original manuscripts, and it reads “Leck mich im Arsch, g’schwindi,” (Kiss my ass quickly). Mozart’s scatological letters and text have been a major source of embarrassment, and we have long tried to suppress, trivialize, or sanitize them, all starting, it seems with his widow Constanze.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Leck mich im Arsch,” K. 231 “Kiss my ass” (Chorus Viennensis; Uwe Christian Harrer, cond.)

Beethoven’s Canon “Kurz ist der Schmerz”

Now, let’s try to understand Ludwig van Beethoven better. Of course, he was a phenomenal and dazzling singularity in the history of art who left his mark on subsequent composers and institutions. But there are still some less explored areas in his oeuvre, particularly his musical jokes and canons. None of these items constitute great music or essential Beethoven, but we find the composer with his shirt left unbuttoned and in a rare jovial mood. Whether he is musically teasing his obese friend and violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh—not only likening him to a donkey but also referring to him as an ass—or delighting in puns on composer’s surnames, Beethoven simply seemed to have had a bit of fun. We also find birthday and Christmas greetings for colleagues and friends, and a good bit of schoolboy humour. When his great benefactor Count Moritz Lichnowsky tried to put Beethoven’s financial affairs in order in 1823, Beethoven responded with a 4-voice canon to the words “Dear Count, you are a fool.” And as a reviewer writes, “the Beethoven who comes across in these canons is one, who, for all his childish unpredictability and irascibility, could also be affectionately childlike, and, above all, good company.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Bester Herr Graf, Sie sind ein Schaf” (Dear Count, you are a fool) (Ensemble Tamanial)

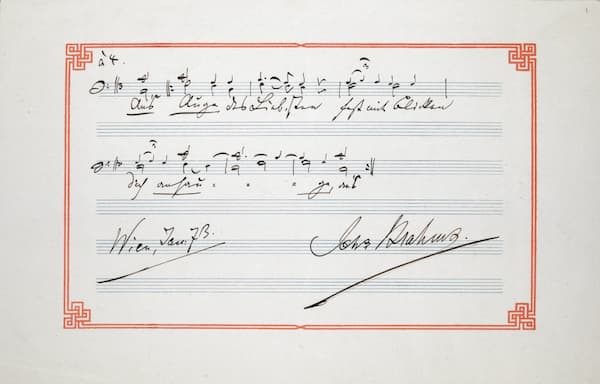

Brahms’ Canon Op. 113, No. 9

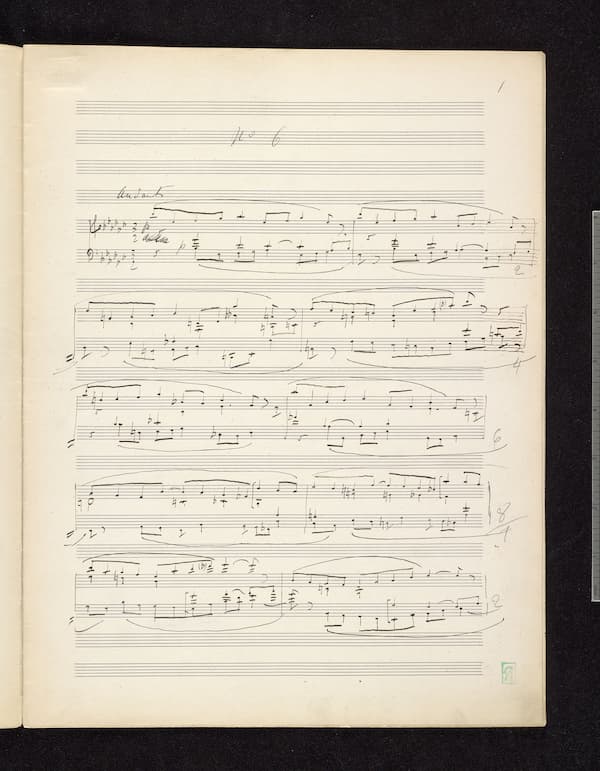

The choral music of Johannes Brahms is illuminated by contrapuntal transcendence. He diligently worked to achieve contrapuntal mastery, which became integral to his musical language. Possibly composed as early as 1858 during his tenure with the women’s choir in Detmold, Brahms published his 13 Canons, Op. 113 only in 1891.

According to Brahms, “these canons are conceived to be sung, not to be listened to,” and the composer also wrote, “I should like to believe that I have enriched domestic singing through my efforts, and wish the same for the singing of canons.” The large majority of these Brahms canons are in unison, with canon No. 6 unfolding in inversion, and Nos. 8 and 9 are canons at the fifth below. The concluding double cannon was inspired by the mediaeval round “Sumer is icumen in” and “Der Leiermann” from Schubert’s Winterreise.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: 13 Canons, Op. 113 (Leipzig Radio Chorus; Wolf-Dieter Hauschild, cond.)