Umberto Boccioni and Ferruccio Busoni at Pallanza

When we look at artists and their friends, sometimes its because, in each of their realms, the artist and the composer may have similar stylistic thoughts. In other cases, however, the works of the two artists may be completely opposite.

Italian artist Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916) was a principal figure in the Futurism movement. Futurism emphasized speed, technology, violence, as embodied in the car, the airplane, or the industrial city.

Boccioni: Umberto Boccioni (self-portrait) (1905)

Futurism started in Italy, with its key figures Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. It then moved to Russia. It was heavily informed by Cubism.

In Gino Severini’s 1912 work, Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, we can see Futurism in action.

Boccioni’s family moved from Reggio Calabria in the south of Italy to Emilia-Romagna, Genoa, Padua, and Catania, Sicily. He studied art in Rome at the Accademia di Belle Arti starting around 1898. Severini, who met Boccioni in 1901, saw in him even then his characteristic mixture of outrage and irony that would guide his future. He studied in several late-19th century style, including Liberty Style (Stile Liberty), which was Italy’s version of Art Nouveau and Divisionist style, which had its beginnings in Georges Seurat’s pointillist work Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte (A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte). In 1906, he moved to Paris where he studied Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles and did a side trip to Russia. By 1907 he was back in Italy and working as a commercial artist. Living in Milan, he met the other members of the future Futurist group and on 11 February 1910, he and his fellow artists signed the Manifesto dei pittori futuristi (Manifesto of Futurist painters). He explained the aesthetics by contrasting them with the Impressionists:

While the impressionists paint a picture to give one particular moment and subordinate the life of the picture to its resemblance to this moment, we synthesize every moment (time, place, form, color-tone) and thus paint the picture. (1914)

Severini: Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin (1912)

(New York: Museum of Modern Art)

His first successful work in Futurism was La cittá sale (The City Rises), painted in 1910. This 2m x 3m painting was his image of a ‘synthesis of labour, light, and movement.’

This work was purchased by the Italian pianist Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) for 4,000 lire in 1912. That was the year Boccioni and Busoni met, as guests in a villa on Lake Maggiore at Pallanza. They were to meet there other times and in 1916, Buccioni painted Busoni’s portrait. Busoni, in 1916, was at the height of his fame. His concert tours met great acclaim (matched with great censure from the critics who didn’t like his interpretations).

Ferruccio Busoni: Etude en forme de variations, Op. 17 (Wolf Harden, piano)

Boccioni: The City Rises (1910) (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

We started this essay talking about style – Busoni did not have Boccioni’s angry and violent style but was known for his more controlled performances. Alfred Brendel writes of Busoni that his playing ‘signified the victory of reflection over bravura,’ i.e., as being more considered and studied than Liszt, for example. One of Busoni’s great contributions to the piano literature was his editions of the works of J.S. Bach for the piano. These were not just straight transcriptions but followed Busoni’s own belief that the performer has to be free to interpret a composer’s intentions. He added tempo markings, articulation and phrase markings, dynamics and metronome markings, all intended to bring Bach both to the quality of the 19th century piano technology and to the aesthetic of the day.

J.S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: V. Chaconne (arr. F. Busoni for piano) (Gordon Fergus-Thompson, piano)

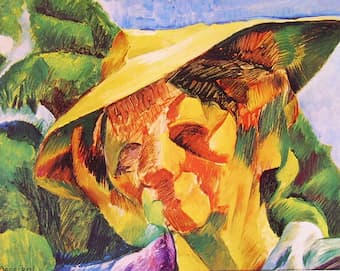

Boccioni: Ritratto della signora Busoni (1916)

(Milano: Galleria d’Arte Moderna)

At Pallanza, Boccioni painted both Busoni and his wife, Gerda Sjöstrand, daughter of the Swedish sculptor Carl Eneas Sjöstrand, in his new figurative style. He had abandoned his earlier styles and now sought to analyze his subject by means of colour. His last painting was his image of Busoni – the man who had bought his first successful work.

Boccioni: Ferruccio Busoni (1916)

(Milano: Galleria d’Arte Moderna)

In the paining of Busoni’s wife, you can see elements of Cézanne and other pre-Cubist painters and Boccioni’s own experiments in using masses of colour. In a different way, Busoni emerges against the blue grey background of the lake and the rocks.

In the last months before his death, Busoni and Boccioni were prolific correspondents. Boccioni had been drafted into the Italian army in May 1916 and was assigned to an artillery regiment; he wrote to Busoni about how terrible the life was. Boccioni died on 17 August 1916 after he was thrown from his horse during a cavalry training exercise and was trampled.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter