Once a musician feels ready he or she might attempt to land a position in one of the major orchestras—Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, London Symphony, Bavarian Radio Symphony, Dresden Staatskapelle, Liepzig Gewandhaus, Leningrad Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic; or perhaps one of the “Big Five”—the top orchestras in the US such as Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, or other excellent ensembles, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, National Symphony, Houston Symphony, St Louis Symphony. Musicians need to learn mountains of repertoire quickly, to saturate themselves with the various styles and approaches to the music, and to acquire the techniques for playing in a section within the entire ensemble. Experience in a less famous orchestra is extremely important.

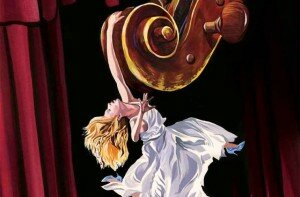

That summer, the summer I turned twenty-five, I was offered several attractive propositions. I turned down a marriage proposal, but said yes to the conductor of the Indianapolis Symphony. He had been watching me carefully. After I played for him privately, when he said, “I want you, (in the orchestra)” I said yes.

The associate principal cello position of the Indianapolis Symphony was a coup for such a young person but my parents’ reaction to the news was disappointing. “Janetkém, you have a contract?” My father asked. “What about auditions? No job until you sign contract.” Such a pessimist, I thought. He always looked at the dark side.

During that summer in Aspen between rehearsals and concerts, I was preparing for the prestigious Munich International Cello Competition in Germany, which would be held in the fall. When several weeks went by without news from Indianapolis, I called the manager. “Hello. This is Janet Horvath and….” Dismayed there was no sign of recognition, I mumbled on, slightly more sotto voce. “I was offered the cello position? By the conductor?”

Strauss

Less than an hour later my phone rang. It was the conductor. “What exactly did you tell the manager, because if he thinks you think you have the job, it will work against you! We are going ahead with auditions. If you win a prize at the competition it will be a feather in your cap, and we can arrange for you to play for the current principal cello as, you know, a formality.”

Telling my father was the worst part. He had been right. Everyone in Aspen had congratulated me on winning the position. What if the audition committee chose someone else in September? After copious tears, I decided to skip the competition. Instead, I worked hours and hours on the excerpts, and traveled to Indianapolis to audition, determined to play whatever they asked for, and however they wanted it—faster, slower, shorter, longer, more legato (sustained), or more staccato (short and crisp), or even standing on my head— to win the job.

Prokofiev: Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, Op. 100

Shostakovich

R. Strauss: Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (Der Bürger als Edelmann) Suite, Op. 60, TrV 228c – IX. Das Diner: Tafelmusik

Shostakovich: Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 – IV. Allegro molto

Following the audition, the principal cellist congratulated me, “beautiful playing. Thank you and good luck.” Good luck? Didn’t I play a perfect audition? An agonizing hour or so later the conductor sauntered in. The committee had completed their deliberations, “Oh, there was never any doubt you’d have the job,” he said.

Following the audition, the principal cellist congratulated me, “beautiful playing. Thank you and good luck.” Good luck? Didn’t I play a perfect audition? An agonizing hour or so later the conductor sauntered in. The committee had completed their deliberations, “Oh, there was never any doubt you’d have the job,” he said. Like many young musicians, I was naïve. I didn’t understand the process for winning an audition.

Orchestras announce a vacancy in the International Musician newspaper. Usually they ask candidates to pay a small fee and to fill out an application. An audition committee from the orchestra is formed, which includes the principal player of the section and eight other members of the orchestra. The conductor attends the final round. Sometimes the first round is done by audiotape. It’s not unusual to have 100 or more applicants for one position. Some orchestras have the candidates play behind a screen to make the process totally anonymous.

The applicants are asked to perform a standard concerto, and in the case of string players, solo Bach. They are sent a list of excerpts to prepare ahead of time—passages from as many as 12-15 different orchestral compositions. A musician will work for months on this repertoire in preparation for what might be a 15-minute audition.

Only the very top candidates are selected to pass to a semi-final round—the ones who show musicality, a lovely sound, perfect intonation, solid rhythm in their solos, and who play the excerpts impeccably. This means not only performing the passages with all of the proper dynamics and markings, in tune and in rhythm, with a beautiful sound, but also conveying an understanding of the style of the music, projecting an awareness of traditional interpretations of the piece—the phrasing, the tempo, knowing where another instrument is featured, the standard or traditional bowing in the case of string players, and where it is common to breathe in the winds.

As a candidate, it’s important to be well-prepared and flexible. The conductor may ask for a different articulation. He or she may even conduct to see how responsive you are. A pre-audition ritual that includes meditation, focusing on the positive, and deep breathing helps. Avoid tiring yourself out practicing until the very moment you walk out to perform. Visualize playing effortlessly. Imagine the space so you are not cowed by playing alone on the large stage.

Musicians aim to be “on” as soon as we begin. It’s only natural that sometimes we’ll miss something. Know that the audition committee has been there. If you mess up, stop, and ask if you might try it again.

The top orchestras may select two or three candidates to play a week with the orchestra. There is really no other way to determine which finalist fits into the group, is easy to get along with, and adds the most to the ensemble.

Not winning an audition isn’t a damning judgement of you as a player or as a person. Even when you play your best, the conductor may be looking for blue, (is seeking a particular quality of sound or style), and you were red that day. It’s not unusual for an excellent player to take 5-10 or more auditions before succeeding.

This is a grueling process, as you can see, but when a musician, after all the years of work, lands a job in an orchestra as prestigious as the Chicago Symphony, it is a dream come true—an opportunity to experience and convey joy to others.