Albert C. Barnes made his money in pharmaceuticals, cashed out his company before the 1929 stock market crash, and ended up creating a unique personal collection of some of the best of the early 20th century French paintings. When the collection was permitted to travel from 1993 to 1995, its appearance in Paris was the cause for an embarrassing comparative display of the French national holdings in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (small) and the Barnes’ collection (enormous). Long housed in a specially built campus in Merion, PA, from 1925, the collection was first opened to the public in 1961, first only in parts (you could not see the entire collection in one visit), and then fully. In 2004, the board finally succeeded in breaking the original foundation documents to permit the entire collection to move from the Philadelphia suburbs into centre city Philadelphia. The new building opened in 2012.

One condition that Barnes had made from the beginning was that the art in the building in Merion must stay as he left it – it could not be moved, loaned out, photographed for postcards, etc. The Merion building was unique because Barnes intended the building to be primarily for education rather than as a museum open to the public. In the new space, Barnes’ original layout – which puts works that he thought you should see together along with his extensive collection of keys – has been preserved.

An Ensemble Wall at the Barnes Foundation

In addition to his collection, Barnes also commissioned work for his original building, including three enormous arch-shaped pieces by Matisse. When you search the collection online, you can see not only the artwork but also an image of the entire wall where it appears. In the image below, there are works by Matisse, Picasso, Afro, Aragon, Modigliani, and Soutine as well as keyhole escutcheons by unknown makers, a spatula, a lamp and a bench. It’s a unique setup found in no other museum and one that definitely reflects the taste of the owner.

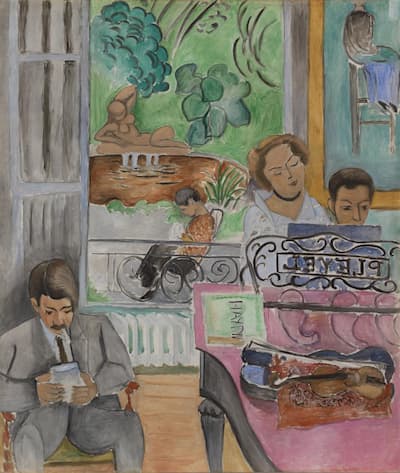

We’ll start with Matisse’s The Music Lesson. Painted in the summer of 1917, the work shows the Matisse family home in Issy-les-Moulineaux, France. The child is being taught piano on a Pleyel piano, a Breitkopf score of Haydn is on the piano in its distinctive green cover, and a violin sits in an open case on the piano. In the garden, Matisse’s wife Amélie knits. His son Jean reads a book, while his daughter Marguerite teaches piano to his son Pierre. On the wall is his painting Woman on a High Stool, now at MoMA in New York, and in the garden is a terra-cotta cast of Reclining Nude I (Aurora), one bronze casting of which is at the Met Museum. We’ve seen in other Matisse paintings how important music was in his life and this is the personal view. It is thought that the violin on the piano was Matisse placing himself in the painting, as it was his violin.

Joseph Haydn: Keyboard Sonata (Andante and Variations) in F Minor, Hob.XVII:6, “Un piccolo divertimento” (Rachel Heard, piano)

Henri Matisse: The Music Lesson, 1917 (Barnes Foundation)

In a more abstract painting, Matisse depicts the Joy of Life (1906). Dancers are at the back of the painting, to be shown more fully in his 1910 work Dance, lovers recline, musicians play on the right on a vertical flute or a recorder and in the front centre a figure plays the classical aulos. Purchased by Gertrude and Leo Stein for their shared apartment at the rue de Fleurus, the work was first shown in the 1906 Salon des Independants and was instantly controversial. It wasn’t controversial in its subject matter – that was a standard – but it contradicted everything taught at the École des Beaux-Art: the style was inconsistent, the figures were out of proportion or grotesquely distorted, and the bold colours were the elements that caused the uproar. However, as its owner Gertrude Stein noted: ‘Matisse had painted Le Bonheur de vivre and had created a new formula for colour that would leave its mark on every painter of the period.’ Picasso saw it at the Stein house, and it was the starting point for the two artist’s long rivalry.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice, Act II: Dance of the Blessed Spirits (arr. for flute and harp) (Nora Shulman, flute; Judy Loman, harp)

Henri Matisse: Le Bonheur de vivre (The Joy of Life), 1905-1906 (Barnes Foundation)

Contrasting with Matisse’s flowing and arabesque designs, this still life by Picasso, in his Cubism style, seems blocky and chunky. The elements of a violin are present: the curly scroll at the top of the finger board, the f-hole from the body of the instrument, the strings coming down to the bridge, and the tailpiece that holds the strings are all shown, but the instrument itself has been sliced into pieces. A long black bottle on the right with a distinctive cap and some sheet music with only a few notes visible complete the image. There are few examples of cubism in the Barnes collection as the owner did not like the style and thought it both banal and academic and that it would only be short-lived.

Gabriel Fauré: Après un rêve, Op. 7, No. 1 (arr. for violin and piano) (Nicola Benedetti, violin; Alexei Grynyuk, piano)

Pablo Picasso: Violin, Sheet Music, and Bottle, 1914 (Barnes Foundation)

The men in their formal top hats, one wearing a fashionable lounge suit and his friend in formal evening dress, contrast with the young women in their more casual clothes. A certain awkwardness seems to be taking place in this meeting of the sexes. Entitled La sortie du conservatoire, the picture, by Renoir, shows students leaving the Paris Conservatoire after classes. The two women stand arm in arm and one of the men has his hand on the other’s shoulder, as if giving him the courage to approach. The first owner of the painting was the composer Emmanuel Chabrier, who never attended the Conservatoire, although he did study composition, violin, and piano privately while he pursued his degree in law. The work, in fact, was not painted outside the Conservatoire, but was painted at his house in Montmartre. There’s no visible music in the painting, except, perhaps for the rolled-up paper, which might be a musical score, but the work was entitled Leaving the Conservatoire when it was sold at the auction of Chabrier’s goods in 1896 after his death. Students and their courtship rituals come to the fore in this work but taking the title as a clue to who these students might be gives us our musical line.

Manuel Blancafort: Hommage a Fauré (Miquel Vaillalba, piano)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: La Sortie du conservatoire (Leaving the Conservatory), 1876–1877

(Barnes Foundation)

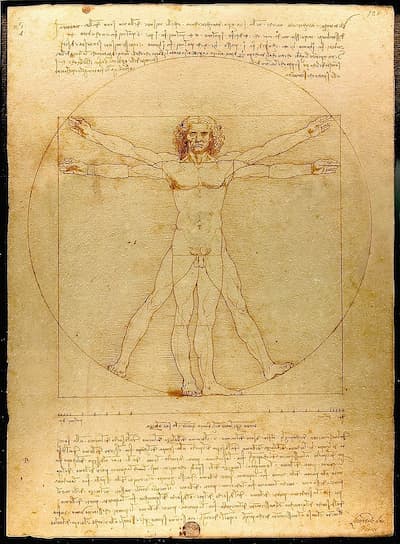

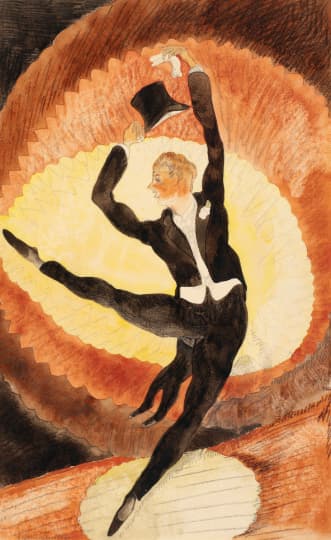

The dancer on the stage leaps high in the air, his hands holding his gloves and his top hat. Behind him, the stage lights almost make him a shadow in their brilliance. We cannot hear or see the music, but it lives in his action. A vaudeville dancer on the American stage was a standard through much of the early 20th century, and yet, at the same time this image recalls the English artist William Blake’s image of Albion, which in itself is derived from Leonard da Vinci’s image of The Vitruvian Man.

Leonard da Vinci: Vitruvian Man, ca. 1490 (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, Italy)

William Blake: A Large Book of Designs: Albion Rose, 1794-1796 (British Museum)

Seeing the image in this context shows that Demuth was well-aware of his antecedents and could carry them into popular cultures.

Paul Schoenfeld: Vaudeville – V. Carmen Rivera (Wolfgang Basch, piccolo trumpet; New World Symphony; John Nelson, cond.)

Charles Demuth: In Vaudeville: Acrobatic Male Dancer with Top Hat, 1920

(Barnes Foundation)

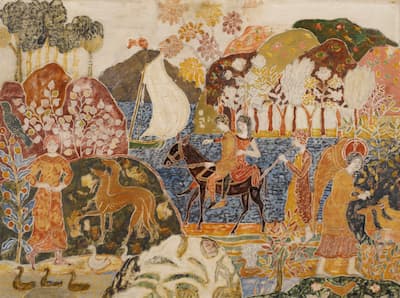

Looking both modern and medieval at once, this painting by Charles Prendergast of Two Figures on a Mule (ca. 1917-1920) draws from medieval European, Byzantine, Chinese, Egyptian, and Persian art. We have an angel, people riding a horse, dogs and ducks, and a boat on the water. Flowers loom as large as trees in the background and colour is everywhere. Behind the horse, a lone figure with red hair plays an absurdly long instrument with one hand.

Charles Prendergast: Two Figures on a Mule, c. 1917–1920. (Barnes Foundation)

Colonial Africa gives Jean Baptiste Guiraud his inspiration for this African harem. In the procession, the instrument of choice is the tambourine, played by men and women alike. The three of the four black men in the centre play large drums. In the front centre lies a man smoking a waterpipe, or hookah. The landscape is generic, the clothing is generic, but behind the dancers are two French flags, pointing to a colonial setting, because this certainly isn’t France.

David Fanshawe: African Sanctus: Credo: Sudanese Dances & Recitations

Jean Baptiste Guiraud: Un Sérail en Afrique (A Harem in Africa), 1884 (Barnes Foundation)

Much of the music in the Barnes Foundation’s images are drawn from fantasy. Prendergast, Demuth, Guiraud all give us music in fantastical contexts. Matisse and Renoir, on the other hand, give us music in its practical form, being learned at conservatory or at home. The Barnes Foundation collection is a unique vision of its creator and in it, music plays an interesting role.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter