Moderato (It.)

Moderato (It.)

‘Moderate’, ‘restrained’, e.g. allegro moderato (‘a little slower than allegro ’).

adv. & adj. Music (Abbr. mod.)

In moderate tempo……. Used chiefly as a direction.

‘Moderato’ is one of those rather ambiguous musical terms, like andante (“at a walking pace”). Literally translated, it means “moderately” – but what does it really mean? At the most basic level, it is a tempo marking, slower than allegretto, but faster than andante. The modern metronome gives a marking of 96 to 100, a very narrow range (and I would always guard against assigning a specific metronome mark to a piece marked moderato, or allegro moderato, or molto moderato.) Like so much else in music, moderato is not just a tempo marking; it also suggests mood and character. It is personal feeling and sense of music, and one person’s moderato might be rather different from another’s, both in terms of tempo and character.

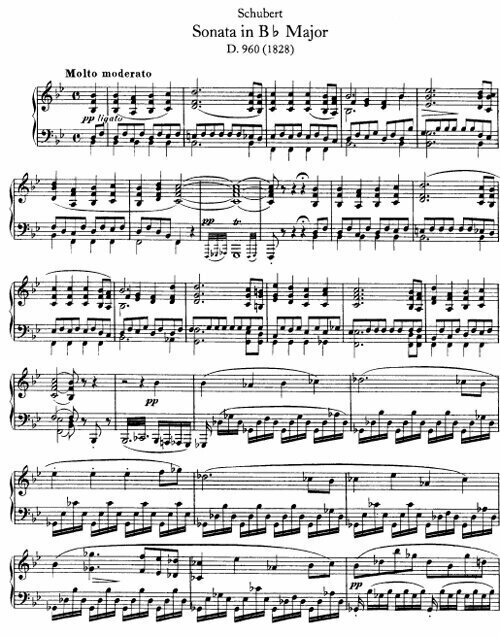

The opening movement of Schubert’s last sonata is marked molto moderato, literally “very moderately”. And taken literally, that could result in a very slow tempo, virtually alla breve (two beats in a bar), which can make the music appear to drag. Schubert also used the German term mässig, implying the calm flow of a considered allegro or “not rushing nor dragging”. There are many, many different interpretations of Schubert’s marking, resulting in some wildly varying lengths of the first movement. Sviatoslav Richter’s is almost self-indulgent at nearly 25 minutes – listening to it, you get the feeling he is thinking about every single note and where to place it; while Maria João Pires brings it in at 20 minutes, which feels both fluid and eloquent.

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-Flat Major, D. 960 – I. Molto moderato (Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-Flat Major, D. 960 – I. Molto moderato (Maria João Pires, piano)

Of course, all these specific timings are rather meaningless: one would not notice the time passing at a good performance unless one was pedantic enough to sit there with a stopwatch! Creating a sense of the music and conveying mood, colour and shading is more important. When I listen to the piece, I always feel the opening movement suggests a great river broadening into its final course before reaching the sea: unhurried but with continual forward motion. There are moments of “other-wordliness” in this movement as well, which demand sensitive rubato playing and some very finely-controlled pianissimos. There are storms too, but these are short-lived, and do not disturb the overall almost hymn-like serenity of the movement.

Frédéric Chopin: Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23 (Lars Vogt, piano)

Frédéric Chopin: Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23 (Jean-Philippe Collard, piano)

In Chopin’s Ballade in G minor, a piece of fluctuating tempos and mercurial moods and textures, the first theme is also marked moderato. Here, I would read this marking as a slower tempo than in the Schubert sonata. The mood is very different too: the key is darker, and the off-beat quaver figures and the rather uncertain harmonies, with the prominent use of diminished and dominant seventh chords to add moments of tension which are not always resolved immediately, create a sense of hesitancy in the music, as if it is not quite sure where it is going. After the fioritura, the opening theme returns, slightly elaborated with a sighing quaver figure, but rather than increase the sense of forward motion, I feel the music becomes more suspended; thus when one reaches the direction agitato, there is a far greater sense of climax. This continues right through to the arpeggiated figures and onwards, in a section marked sempre piu mosso. After the great, memorable second theme is heard, the first theme returns, this time in A minor, and the music returns to the moderato tempo and mood of the opening. Here once again, uncertain harmonies are used to contrive a feeling of suspense, while the insistent repeated low E’s in the bass tether the music even more firmly in one place. This is a useful device for introducing another climax, which seems to suddenly free itself from the restraints of the moderato marking; the restatement of the second theme on a far grander scale than its first appearance.

In Chopin’s Ballade in G minor, a piece of fluctuating tempos and mercurial moods and textures, the first theme is also marked moderato. Here, I would read this marking as a slower tempo than in the Schubert sonata. The mood is very different too: the key is darker, and the off-beat quaver figures and the rather uncertain harmonies, with the prominent use of diminished and dominant seventh chords to add moments of tension which are not always resolved immediately, create a sense of hesitancy in the music, as if it is not quite sure where it is going. After the fioritura, the opening theme returns, slightly elaborated with a sighing quaver figure, but rather than increase the sense of forward motion, I feel the music becomes more suspended; thus when one reaches the direction agitato, there is a far greater sense of climax. This continues right through to the arpeggiated figures and onwards, in a section marked sempre piu mosso. After the great, memorable second theme is heard, the first theme returns, this time in A minor, and the music returns to the moderato tempo and mood of the opening. Here once again, uncertain harmonies are used to contrive a feeling of suspense, while the insistent repeated low E’s in the bass tether the music even more firmly in one place. This is a useful device for introducing another climax, which seems to suddenly free itself from the restraints of the moderato marking; the restatement of the second theme on a far grander scale than its first appearance.

So, one could argue here that the use of moderato at the opening of the piece, and its reappearance later on, is a very deliberate device which serves to create moments of great tension, suspense and climax.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter