Felix Mendelssohn was born in 1809 in Hamburg, Germany. He became one of the most dazzling talents in classical music history and helped to lay the ground for classical music’s Romantic Era.

Eduard Magnus: Mendelssohn, 1846

Here are a few facts about his life and music:

- Mendelssohn was one of the most impressive musical prodigies of all time…maybe even the most impressive. He wrote some of the best-loved works in the entire classical music canon when he was in his teens.

- Mendelssohn served as a bridge between the Classical and Romantic eras. His music effortlessly balances elegance and emotion.

- He’s especially famous for his music that references inspirations outside of music, like works of literature or geographic areas.

- He also became famous for his Songs Without Words – brief songs that seem to tell a story but, as the title suggests, feature an instrumentalist playing the melodic line instead of a singer singing it.

Intrigued? Here are ten works to get you started discovering Mendelssohn and his world:

Octet (1825)

As its name suggests, an octet is a work for eight instruments. In this case, that’s a double string quartet: four violins, two violas, and two cellos.

As you can imagine, it is extremely difficult to compose independent parts for eight different musical instruments while still retaining an appropriate balance between forces.

Mendelssohn accomplished this feat with aplomb when he was only sixteen.

Composer’s age aside, the work is acknowledged to be one of the great achievements of nineteenth-century chamber music. Highlights include a soaring opening movement, a fairy-like scherzo, and a furious fugato at the end, where each instrument begins playing in turn.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture (1826)

This overture has a similar mysterious, sparkling atmosphere to the third movement of his octet. (That’s fitting, given that he wrote this overture the year after he wrote the octet.) But instead of just eight instruments, here the seventeen-year-old Mendelssohn enlists the forces of an entire orchestra.

The overture was inspired by William Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream and its weird and wonderful story of love and fairy magic.

Hebrides Overture (1830)

From 1829 to 1831, Mendelssohn went on a European grand tour, a form of education and horizon-broadening commonly offered to young men of his class and generation. One of his stops, Fingal’s Cave in the Hebrides, Scotland, made a huge impression on him.

The young Felix Mendelssohn

“In order to make you understand how extraordinarily the Hebrides affected me, I send you the following, which came into my head there,” he wrote to his composer sister Fanny. He included the theme of this overture for her to enjoy.

This work was unique in that it wasn’t the beginning of any kind of dramatic work or even linked to any work of literature, period. This makes it an early example of a tone poem, paving the way for countless future works of orchestral music inspired by history, art, and natural wonders.

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1830-1833)

This concerto was dedicated to and written for German pianist and composer Delphine von Schauroth, who Mendelssohn fell a bit in love with.

Inspiration came fast and furious. “I wrote it in but a few days and almost carelessly,” Mendelssohn reported.

Several characteristics mark this out as a Romantic Era concerto, as opposed to a Classical Era one. For starters, the orchestral opening is brief, which increases the importance of the soloist’s showy part. And that showy solo part is stormy and dazzling.

In addition, the movements are linked together, creating an improvisatory feel—an innovation that Mendelssohn also employed in his violin concerto.

Symphony No. 4 (1833)

After going to Great Britain, Mendelssohn made his way to Italy, where he was inspired to write a symphony.

Once again, he reported his creative progress to Fanny: “The Italian symphony is making great progress. It will be the jolliest piece I have ever done, especially the last movement.”

It is indeed a jolly piece: rollicking, exuberant, and just plain irresistible.

Its finale (which starts at 23:00 in the recording above) is a breakneck saltarello, a dance that originated in Italy. This saltarello gave the work its Italian nickname.

Songs Without Words, Book 2 (1833-34)

Over the course of his career, Mendelssohn wrote eight volumes of six brief solo piano pieces each.

During the mid-nineteenth century, an emerging middle class created a demand for sheet music for the domestic market. These songs filled this commercial niche perfectly and became very popular.

One of the most famous selections from the second book is the second song. It was written as a present for Fanny upon the birth of her son, Sebastian (named after Johann Sebastian Bach, of course).

Piano Trio No. 1 (1839)

Years earlier, in 1832, Mendelssohn had written to Fanny and mused how he would like to write a piano trio with an intricate, important piano part. The trio he had in mind would come to life in 1839.

With this work, Mendelssohn has decidedly left the Classical Era. Less emphasis is placed on restraint and intellect, and all of the parts are virtuosic and emotionally demonstrative.

That said, the fairy-like scurry of the Scherzo (17:35 in the recording above) absolutely calls to mind Mendelssohn’s earlier works, like the octet or Midsummer Night’s Dream overture.

Songs Without Words, Book 5 (1842-44)

Here’s another of the most famous of the Songs Without Words: the Spring Song.

This is a lovely, fresh, even coy portrait of the delights of spring. The many grace notes give the piece a pleasantly tipsy feeling.

Barenboim plays Mendelssohn Songs Without Words Op.62 no.5 in A Minor – Venetian Gondellied

Another famous piece from this book is the Venetian Gondellied, or Venetian Gondolier’s Song. Its time signature and rhythms call to mind the canals of Venice. While listening, one can easily imagine reflections on the water, with oars dipping through them. It’s magical.

Violin Concerto (1845)

The Mendelssohn violin concerto is widely considered to be one of the best concertos ever written for that instrument.

It is both passionate and perfectly proportioned. Its dramatic, virtuosic opening movement leads directly into a heart-rending slow movement.

Afterwards, there is a mischievous bridge that heralds a fleet, fairy-like finale, once again calling to mind the vivacious sparkle of his early works. (That finale begins at 22:51 in the recording above.)

Elijah (1846)

Throughout his life and career, Mendelssohn admired large-scale religious choral works, particularly oratorios by Bach and Handel.

He threw his own hat in the ring with his oratorio Elijah, a two-hour extravaganza inspired by the story of the Old Testament prophet Elijah.

It was premiered in 1846 in Birmingham, England. The London Times reported, “Never was there a more complete triumph – never a more thorough and speedy recognition of a great work of art.”

It has been a favourite with choral groups for generations.

Conclusion

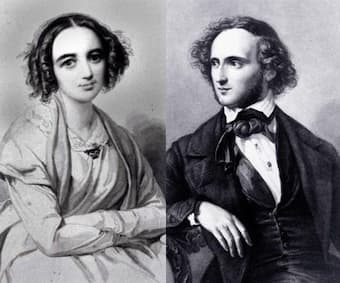

Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn

In May 1847, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel died suddenly of a stroke that she had while rehearsing one of her brother’s cantatas.

Felix was absolutely devastated by the death of his confidant. In November 1847, he died of the same cause. He was only 38 years old. The loss to music was incalculable.

Today Felix Mendelssohn is celebrated as one of the great composers who helped to pave the way for a generation of new romantics.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter