Ever since I was a little child, I listened to recordings by Yehudi Menuhin. In every single note that phenomenal violinist produced fantastic intensity and emotion. I remember listening to Bach’s Air on a G string, and I had never heard anything so beautiful. There is a reason he was considered the “Violinist of the Century.”

Yehudi Menuhin

As a child prodigy, Menuhin immediately captured the imagination, and at his peak, he achieved a spiritual dimension in his playing that radiated warmth and humanity. His career spanned 75 years, and there is hardly a work in the violin repertory, sonata, concerto, chamber music, or showpieces that Menuhin did not record. He was the recipient of countless awards and distinctions, and he also started the Yehudi Menuhin School, near London, for musically gifted children.

Musically speaking, Menuhin did not live in the past but championed contemporary music. As a result, he commissioned or was the recipient of 40 works of music specifically dedicated to him. I won’t be able to feature all commissions in this blog, and whether they are masterworks or not, they are sounding testaments to an incredible musician and human being.

Yehudi Menuhin Plays Bach’s Partita for solo violin No 3 in E major

Béla Bartók: Sonata for Solo Violin

Béla Bartók in New York, 1944

From the very beginning, Yehudi Menuhin was attracted to the works of Béla Bartók. He once wrote that Bartók suited his temperament. He first met the composer prior to a performance of Bartók’s First Violin Sonata at Carnegie Hall. Menuhin remembers:

“He had already drawn up an armchair, music on his lap, pencil in his hand, the real Hungarian strict professor. No warmth, no how are you today. So, I unpacked the violin and started playing. After the run-through of the first movement, Bartók said, “I did not think works could be played that beautifully until long after the composer was dead.”

On the spot, Menuhin commissioned a solo sonata. He reports, “well, here was my chance. I’m sure he would have written a concert for me because, at that moment, he would have done anything I asked, but he gave me the great Sonata in four movements, without a doubt the greatest work for solo violin since Bach.”

Bartók was present for the first performance on 26 November 1944. “When there is a real great artist,” he said, “then the composer’s advice and help is not necessary; the performer finds his way quite well, alone. It is a happy thing that a young artist is interested in contemporary works.”

Béla Bartók: Sonata for Solo Violin (Ivry Gitlis, violin)

Frank Martin: Polyptique

Frank Martin, 1959

For the opening of the 1973 IMC conference in Geneva, Menuhin commissioned the Swiss composer Frank Martin. Menuhin thought very highly of Martin, and he described him as “after Bartók perhaps the most important composer whom I have commissioned. He told me that on receiving the IMC request he had not known what he would write until one day he found himself in Siena.”

During a museum visit, he saw a polyptych of scenes from the Gospel… Palm Sunday, the Last Supper, Judas, the Garden of Gethsemane, the Judgement, and the Glorification. “I told him I was grateful he had spared me the Crucifixion.” Martin decided that the work was to be scored for double string orchestra when Menuhin’s wife Diana suggested developing the music so that Yehudi could be the Evangelist as well as Jesus.

Diana Menuhin, nee Gould, knew all about dramaturgy and pacing. She was, after all, the most famous British ballerina, and Anna Pavlova called her the “only English dancer with a soul.” Menuhin had married Dina Menuhin in October 1947, and they became inseparable. They even signed their names “Yehudiana.”

Martin agreed to Diana’s suggestion and the orchestra supplies the apostles, crowd and atmosphere. Martin told Menuhin, “If the last movement was to be the Resurrection, then it’s got to end up on a very high note.” A biographer wrote, “Yehudi bestowed on Polyptique a disappointingly bland seal of approval, describing it as one of the works of which the twentieth century can be proud to bequeath to the future.”

Frank Martin: Polyptique (Yehudi Menuhin, violin; Menuhin Festival Orchestra; Zürich Chamber Orchestra; Edmond De Stoutz, cond.)

Ernest Bloch: Abodah

Ernest Bloch, 1917

Ernest Bloch was invited to teach at the newly named San Francisco Conservatory of Music in 1923, an appointment he took up in 1925. He was named the director of the Conservatory and stayed in that position until 1930. Bloch quickly became a Menuhin family friend, and he wrote to Moshe Menuhin, “When your kids asked me to say good night in their little beds I could have cried. How Christ was right! Only children know the Truth! Your children are extraordinary and yet so normal, healthy, and so true! What a superb living example of eugenics and what hope…”

Bloch also heard the young Menuhin perform in San Francisco, and he was so moved that he felt compelled to write a work for him. That work was titled “Abodah” (God’s Worship), and subtitled “A Yom Kippur Melody.” Menuhin performed the work with his teacher, Louis Persinger, in December 1928. The melody is a traditional Eastern European Ashkenazi synagogue chant and consists of 20 basic motifs of varying length and character. Bloch always believed that the priority in his compositions was to give expression to the whole gamut of human emotions.

Ernest Bloch: Abodah (Hagai Shaham, violin; Arnon Erez, piano)

Ernest Bloch: Suite No.1 for Solo Violin

Bloch produced a further arrangement with Nigun, a work Menuhin played as a boy as well. The two artists remained close friends throughout, and in 1957, Menuhin performed the Bloch Violin Concerto in New York City. That work had been dedicated to Joseph Szigeti, who premiered it in December 1938. Menuhin’s performance elicited high praise from the composer and from a critic, who wrote, “every facet of its eclectic style, every phrase and every measure, was delivered with the assurance of a musician whose interpretation is going just the way he wants it to.”

In 1958, Menuhin visited Bloch in California with the aim of eliciting a commission. “They sat down talking happily, discussing the solo suites Menuhin had commissioned, mulling over the days of old.” Menuhin would later describe the two Bloch Suites as “expressive, melodic, classical in a manner that calls to mind latter-day Bach.” He did record them in the mid-1970s, and the first Suite is scored in four movements played without a break. A critic writes, “as in many Bloch compositions, the cyclic element is present here, with restatements of themes from previous movement.”

Ernest Bloch: Suite No.1 for Solo Violin (Yehudi Menuhin, violin)

Andrzej Panufnik: Violin Concerto

Andrzej Panufnik

In 1971, Yehudi Menuhin approached Andrzej Panufnik for a violin concerto. Panufnik was offered £200, but the composer was looking for a bit extra. Menuhin turned down that request, but Panufnik went on composing anyway. Menuhin needed the work quickly, but the composer expressed doubts about completing it in time. Apparently, Menuhin told him, “No problem, just start with the last movement.”

Panufnik was supposedly very superstitious and his most successful compositions had been dedicated to his wife Camilla. Panufnik actually contacted Menuhin, and he “replied with the utmost grace that, of course, it should be for Camilla and that he would dedicate his performance to her too!” In his memoirs, Panufnik remembered, “I was moved to find that Yehudi had taken the trouble to memorize the whole work. Though our original intention had been that he should direct the Concerto from the violin, the cross-rhythms of the fast last movement turned out to be too tricky and dangerous.”

Andrzej Panufnik: Violin Concerto (Piotr Pławner, violin; Berlin Chamber Symphony Ensemble; Jürgen Bruns, cond.)

Panufnik took great care to showcase the warm, expressive qualities of Menuhin’s playing. The composer had developed a “three-note cell language,” limiting himself to just three pitches and their intervening intervals, and found to his amazement, “new harmonies, new expressions, new sound colours.” The opening movement is almost entirely built on three intervals but with a great variety of rhythmic, harmonic, and coloristic expressions. According to Panufnik, “I intentionally avoided any display of empty virtuosity but explored to the utmost Yehudi’s rare powers of spirituality.”

Nigel Kennedy: Dedications, No. 4 “Solitude (for Yehudi Menuhin)”

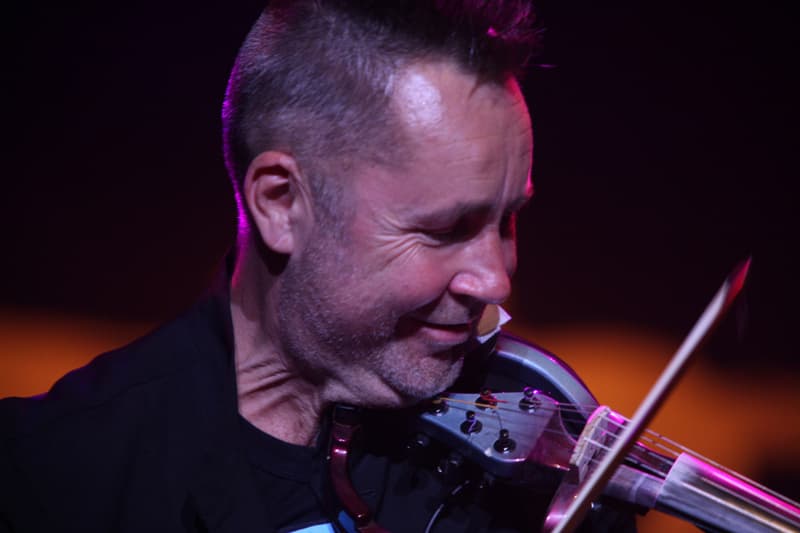

Nigel Kennedy

Menuhin’s legacy continues to inspire and recently turned the violinist Nigel Kennedy into a composer. For Kennedy, “Menuhin gives me a direct route back to the music of Bach. His teacher Enescu was, after all, the man who rediscovered the Bach solo violin sonatas, and Yehudi was a serious Bach interpreter. Yehudi was a great melodist as well, and although he was not technically brilliant, two notes from him were generally worth 1000 of those

played by his contemporaries or the following generation.”

Kennedy was a student at the Yehudi Menuhin School, and without him, “I would probably not be playing classical music at all,” he explained. Menuhin is immortalized in Kennedy’s “Dedications,” tuneful pieces that straddle pop, jazz, folk, and easy listening. Each movement is dedicated to a different artist, and No. 4, titled “Solitude,” specifically references Yehudi Menuhin.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Nigel Kennedy: Dedications, No. 4 “Solitude (for Yehudi Menuhin)” (The Stella; Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra)