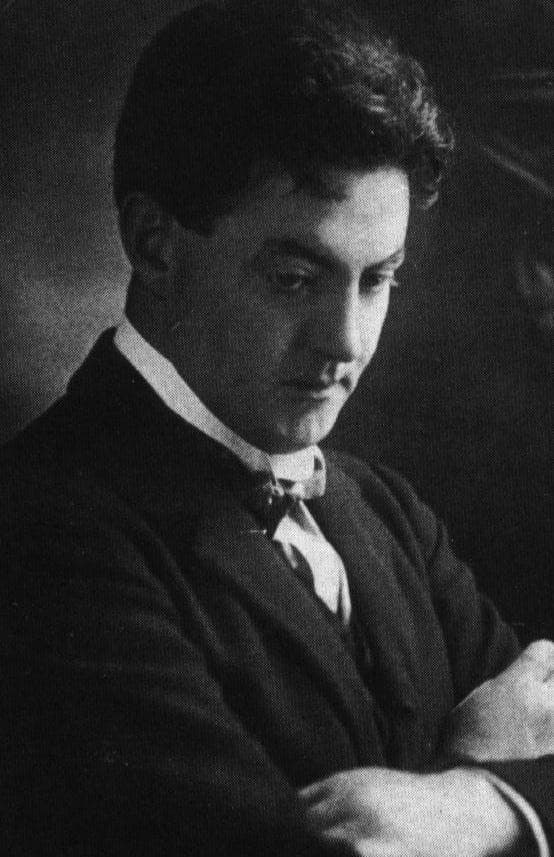

The Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti (1892-1973) carried the nickname “The Scholarly Virtuoso.” That nickname is hardly surprising as Szigeti authored a number of books. Among them, we find a pedagogical treatise addressing technical challenges and innovations in twentieth-century repertoire, and concepts that “connected technique to musical expression.” His detailed analysis of the ten Beethoven violin sonatas was written, according to an editor, “with deep insight, and above all with devotion. He approaches these works with the dedicated love of a sensitive artist and a warm human being.”

Joseph Szigeti

Critics have suggested that “Szigeti’s performing technique was not always flawless and his tone lacked sensuous beauty, although it acquired a spiritual quality in moments of inspiration.” You will find the words “devotion” and “integrity” in a great many descriptions of his performances. However, Szigeti once told a student, “disregard what critics, audiences, and even your colleagues say which is flattering. Don’t be satisfied with a public success; prove your worthiness to your own conscience.”

Szigeti was a strong advocate of new music, and “composers love to dedicate their music to him because he had a unique affinity for the modern idiom.” Szigeti writes, “We violinists must be ever more prepared, mentally and technically, for new difficulties coming from modern composers. They are less and less inclined to mold their musical ideas after the pattern of traditional technique and we ought to welcome this.” This kind of openness to contemporary musical expressions made Szigeti a favorite with contemporary composers, and he received dedications throughout his life. Szigeti’s passion for exploring new music gave composers the confidence to express themselves without inhibition. Let us meet some of these composers and the violin masterworks that Joseph Szigeti inspired.

Hamilton Harty: Violin Concerto

Hamilton Harty

Hamilton Harty: Violin Concerto (Ralph Holmes, violin; Ulster Orchestra; Bryden Thomson, cond.)

Szigeti was only seventeen years old when Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) composed a violin concerto for him. Szigeti remembers, “The earliest of my many associations with composers came before I was twenty, with the concerto which Hamilton Harty dedicated “To Joska Szigeti, in Friendship,” and which I suspect set the pattern for my subsequent approach to other such tasks. Harty was then, around 1908, England’s premier accompanist; and my working at his manuscript concerto, with him at the piano coaxing out of his instrument all the orchestral color which he had dreamed into his score, was probably decisive in forming what a long-suffering and excellent pianistic partner of mine later termed my ‘expensive tastes in accompanying.’” The work premiered in 1909, and Szigeti subsequently performed it a number of times in London before it gradually found its way into the repertory. Szigeti recalls, “I had the somewhat paternal or rather god-fatherly satisfaction of hearing this disarmingly charming work more than a quarter of a century after my introducing it.”

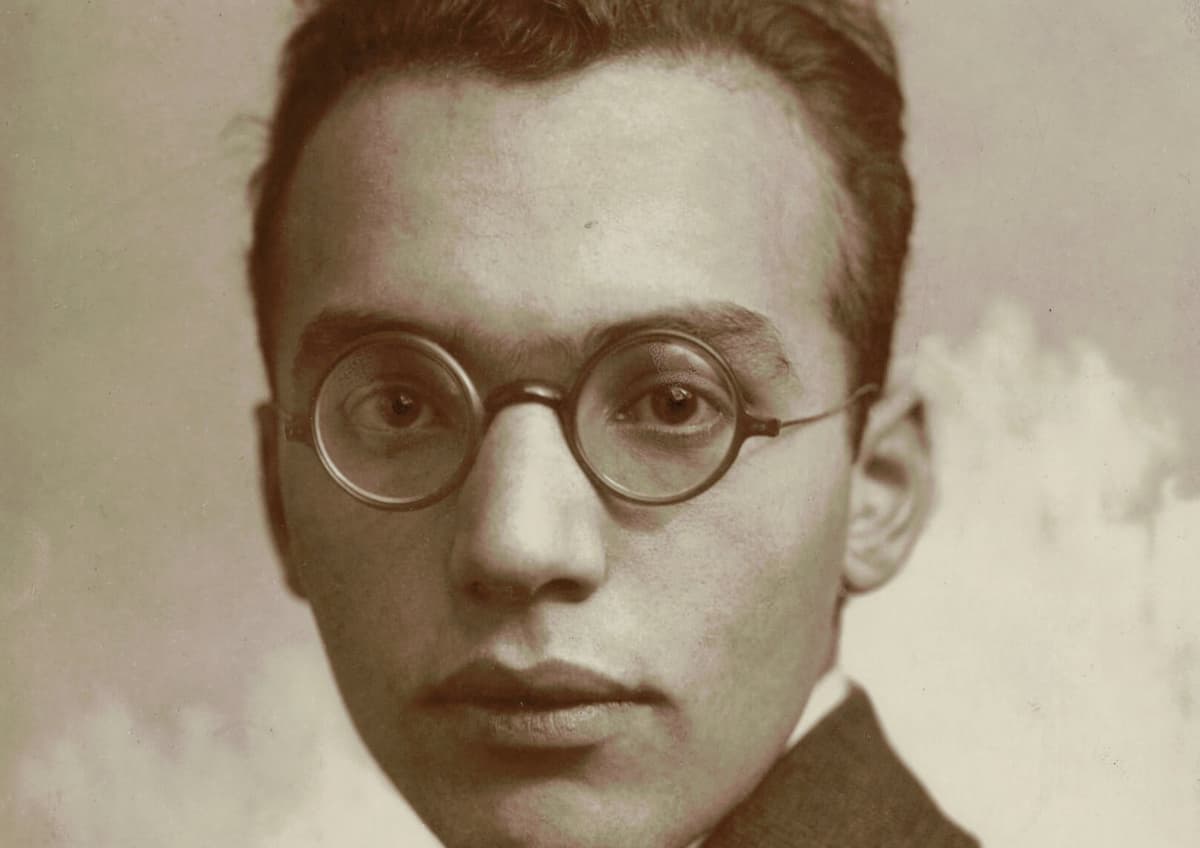

Sergei Prokofiev: Five Melodies, Op. 35bis, No. 5

Sergei Prokofiev in 1918 © Wikipedia

Sergei Prokofiev: Five Melodies, Op. 35bis, No. 5 Andante non troppo (David Oistrakh, violin; Frida Bauer, piano)

Marcel Darrieux might have premiered Prokofiev’s first violin concerto, but the work became inseparably identified with Joseph Szigeti. As Carl Flesch writes, “future generations will see the work through his eyes and will consider his performance a standard difficult to equal, impossible to surpass.” Prokofiev himself announced, “that Szigeti is the greatest interpreter of my Concerto.” The premiere of the concerto took place during Prokofiev’s self-imposed exile in Paris, and that period also saw the arrangement of his Five Melodies for violin and piano. The original version for voice and piano was composed during a tour of California in 1920 and premiered in March 1921 by the soprano Nina Koshetz. The Five Melodies are “little miniatures of intense lyricism and lively character. Their beauty derives from the juxtaposition of very different moods and characters: intense lyricism is contrasted with unusual, diatonic harmonies, with occasional moments of humor and Oriental flavor.” Each of the melodies is dedicated to a particular violinist. The 1st, 3rd, and 4th are dedicated to Paul Kochanski, the 2nd to Cecilia Hansen, and the 5th to Joseph Szegeti.

Kurt Weil: Concerto for Violin and Wind Orchestra

Kurt Weil

Marcel Darrieux was a member of the orchestra at the Opéra-Comique, and simultaneously concertmaster of the “Concerts Koussevitzky.” As we have seen, Darrieux is primarily remembered for having played the premiere of Prokofiev’s first violin concerto. However, it is not general knowledge that he also premiered the Concerto for Violin and Wind Orchestra by Kurt Weil, a work dedicated to Joseph Szigeti. In 1924, Weill wrote to his publisher, “I am working on a concerto for violin and wind orchestra that I hope to finish within two or three weeks. The work is inspired by the idea, one never carried out before, of juxtaposing a single violin with a chorus of winds.” Darrieux premiered the work at an International Society for Contemporary Music Concert in Paris in 1925, but the first performance in Weill’s hometown of Dessau caused a bit of a scandal. Weill writes, “I was stupid to give this somewhat rough, abstract, completely dissonant piece to the Dessauers, who are the most ignorant and philistine of all. It will be unanimously rejected.” The philosopher and social critic Theodor Adorno wrote, “There is a strong trace of Stravinsky to be found in the classical, masterly clarity of the sound and in much of the wind writing… Weill relinquishes objective realism in favor of the dangerous, surrealistic realm he inhabits today. The piece stands isolated and alien: that is, in the right place.”

Alfredo Casella: Violin Concerto

Alfredo Casella

Alfredo Casella: Violin Concerto in A Minor, Op. 48 (Mathias Wollong, violin; Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

The world premiere performance of Alfredo Casella’s Violin Concerto, dedicated to Joseph Szigeti, took place in Moscow on 8 October 1928. The circumstances of that performance, however, were rather unusual. Within the new social order of the Russian Revolution, a conductorless orchestra called “Persymphans” had been created. Szigeti recalls, “after decades of playing concertos with conductors who coordinate a soloist’s performance with that of the orchestra, who synthesize the whole and mediate between the two when there are discrepancies in conception, I found the contrast of these entirely new working conditions stimulating.” And he continues, “at rehearsal, there was a workshop atmosphere generated by proud artisans bound together in the common task of making good music. Everybody had the right to have his little say on occasion, but bickering, backbiting, and sycophancy had no place in this setup… We even gave a world premiere, that of Casella’s concerto, dedicated to me.”

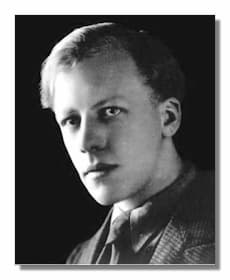

Alan Rawsthorne: Violin Sonata

Alan Rawsthorne

Alan Rawsthorne: Violin Sonata (Peter Sheppard Skærved, violin; Tamami Honma, piano)

Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971) only turned to the serious study of music at the age of nineteen, having initially made a start in both dentistry and architecture. As his biographer writes, “he quickly found his own, thoroughly individual voice, and throughout a long, prolific career he remained faithful to the basic constituents of his style… Hindemith has been named as an influence, as have Prokofiev and Bartók, but they are merely passing shadows that color the music fleetingly; never, even in the earliest published works, does it sound like anything but Rawsthorne.” Szigeti commissioned Rawsthorne in 1958 to compose a violin sonata, and the composer responded with a perfectly proportioned work, “rooted entirely in a clash of D Major/minor against E flat.” It rises above the level of a character study, and the “final violin phrase of the introduction clearly shows that the Scotch snap is more of a Hungarian snap, with a Bartókian phrase presumably in tribute to Szigeti’s Hungarian heritage.”

Frank Martin: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Frank Martin

Frank Martin (1890-1974) equated the sound of the violin with a performance of the Beethoven violin concerto performed by Szigeti in 1921. As he wrote to the violinist, “I have never forgotten your playing.” Martin’s violin concerto, dedicated to Szigeti, “must be counted as one of the finest 20th-century works in the genre. It’s a very beautiful and lyrical work. The opening orchestral tutti alone instantly establishes an unforgettable, magical atmosphere, an amalgam of impressionism, jazz, modal harmony, and a touch of 12-tone technique.” The composer relates, “The violin establishes a mysterious and somewhat fairytale-like atmosphere,” and Paul Sacher conducted the premiere performance with Hansheinz Schneeberger in Basel on 24 January 1952. A critic described it as “a work of great beauty, clarity, restraint, and dignity, showing Martin’s skill in ”combining and contrasting unobtrusively original sonorities…The textures are marvelously luminous and have a translucence and limpidity all their own.” To be sure, Martin’s concerto dedicated to Szigeti is among the most outrageously neglected works of the 20th century.

Béla Bartók: Rhapsody No. 1

Béla Bartók

Joseph Szigeti remembered visiting Béla Bartók in his villa in the hills of Buda. He writes, “His tables, couch, and piano were littered with those hard-earned discs of folk fiddlers, mostly unaccompanied, which he had recorded during many epic years of folklore exploration. He played them to me while I followed the intricate, almost hieroglyphic signs on the literal transcriptions he has made of these, as he has of thousands of others. Putting me to the test: whether I would recognize the sometimes infinitesimally small rhythmic or melodic shreds that went into the Rhapsody No. 1, which he dedicated to me in 1928; making the distinction, while discussing these themes, between the unimaginative, premeditated incorporation of folklore material into a composition, and that degree of saturation with the folklore which unconsciously and decisively affects the composer’s melodic invention, his palette, his rhythmic imaginings.” In fact, Bartók originally composed his two Rhapsodies for Violin and Piano, which he simply entitled “folk dances” specifically with Joseph Szigeti and Zoltán Székely in mind, and only subsequently orchestrated the piano accompaniment.

Ernest Bloch: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Ernest Bloch in 1917

Ernest Bloch and Joseph Szigeti enjoyed an especially close relationship. They first collaborated in 1909, with “Bloch in his capacity of fledgling conductor, and Szigeti as a teen-age soloist in the Mendelssohn Concerto.” As Szigeti writes, “Since then how many gaps of long years during which we wouldn’t meet or even hear from each other, and still, what continuity in our friendship! How many milestones in these thirty-odd years: the Sonata, the concerto, the Baal Shem Suite, which I recorded as early as 1926 and which was, I believe, the first work of his ever to be recorded.” Bloch dedicated Nuit exotique to Szigeti in the autumn of 1924, which “represents a fusion of two of the dominant themes of Bloch’s inspiration, the ideas of ‘night’ and of the ‘exotic.” Bloch’s Violin Concerto portrays, in the words of the composer, “…the complex, glowing, agitated soul that I feel vibrating through the Bible… the freshness and naiveté of the Patriarchs, the violence of the prophetic Books; the Jew’s savage love of justice; the despair of Ecclesiastes; the sorrow and the immensity of the Book of Job; the sensuality of the Song of Songs… it is all this that I endeavor to hear in myself and to translate in my music.” When Szigeti performed the première in Cleveland on 15 December 1938, with Dimitri Mitropoulos conducting, Arthur Berger, of the New York Herald Tribune, exclaimed, “…There is scarcely a work in the whole category of art music in which Jewish associations are stronger.”

Alexander Tansman: Five Pieces for Violin and Chamber Orchestra

Alexander Tansman

Alexander Tansman: Five Pieces for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (Piotr Pławner, violin; Berlin Chamber Symphony Ensemble; Jürgen Bruns, cond.)

A music critic wrote, “Szigeti offered new vistas of imagination, breadth of vision, grandeur of spirit, sincerity of purpose, ineffable sensitivity and the exhilaration which accompanies daring new musical explorations.” Isaac Stern considered him “one of the most profound musicians I have ever known,” and after a recital at Carnegie Hall, he wrote, “It was one of the most ennobling performances I have ever heard. Nobody in the hall breathed. You were not listening to a performance of someone standing on the stage at Carnegie Hall; you were surrounded by a golden aura of music.”

Alexander Tansman (1897-1986) met Szigeti while on tour in America. Szigeti quickly commissioned Tansman, and the composer responded with his Five Pieces for Violin and Chamber Orchestra, first performed in Carnegie Hall in 1930. Essentially, Tansman composed individual movements in the character of a Baroque suite, which reflected his belief that “in music the present will always reflect the past and all its achievements. In my opinion, it is ludicrous to deny what one owes to one’s predecessors for fear that they might affect one’s own personality. Some influences are blinding and all absorbing, others are conscious and welcome. I do not aspire to be a modern composer; I simply wish to be a composer of this time.” Tansman would follow up with his Violin Concerto in 1937, once more dedicated to Szigeti.

Eugène Ysaÿe: Sonata for Solo Violin in G minor, Op. 27, No. 1

Eugène Ysaÿe

In 1923, Eugène Ysaÿe attended a performance by Joseph Szigeti. The entire concert was dedicated to Ysaÿe’s favorite composer, Johann Sebastian Bach. Deeply moved and inspired, Ysaÿe went to work and over the course of twenty-four hours sketched out the six sonatas Opus 27. For one, he was looking to compose a cycle of six works for unaccompanied violin modeled after Bach. In addition, he tailored each sonata to a different virtuoso, “capturing something of each performer’s style in the piece for whom it was written.” It was Szigeti’s playing that inspired the entire Ysaÿe set, and the first Sonata, dedicated to Szigeti, closely follows the form of the Bach G-minor Sonata. Presenting constant technical and musical challenges arising from a dense web of counterpoint, Ysaÿe freely incorporates a Szigeti specialty, “the use of sixths in the whole tone scale in double-stopping that involves smooth changes of position and string.” This is the longest sonata of the set as it also features a tenderly nostalgic third and a synthesis of virtuosity and seriousness in the fourth movement. As Szigeti was looking to reintroduce audiences to the many splendors of the Italian Baroque, he also fashioned a multitude of transcriptions and arrangements; we will look at some of these in a follow-up article.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter