Chopin of the Créoles

© Wikimedia Commons

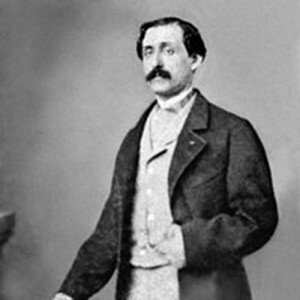

Louisiana-born Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869) spent most of his life as a touring concert pianist. Son of a Jewish businessman and a Créole mother, the boy was quickly recognized as a musical prodigy and departed for Europe at the age of 13. He studied French literature, poetry, fencing, and horseman ship, and he made the acquaintance of Sigismund Thalberg, one of the supreme piano virtuosos of his day. His dream of enrolling at the Conservatoire de Paris did not come true, as Pierre Zimmerman, head of the piano faculty, commented, “America is a country of steam engines not musicians.” Undeterred, Gottschalk continued his music studies and on 2 April 1845, he stepped into the public limelight at the Salle Pleyel. Frédéric Chopin was in the audience, and supposedly remarked, “Give me your hand, my child; I predict that you will become the king of pianists.” The teenage sensation took the salons of Paris by storm, and he produced his first compositions. Finding inspiration in his Louisiana Créole roots, in his early pieces Gottschalk transformed West Indian dances into exotic miniatures that made him a household name throughout France.

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Bamboula, Op. 2

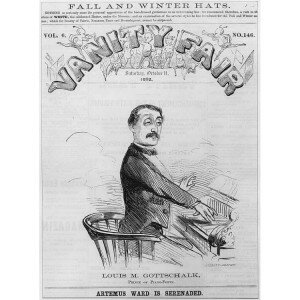

Even Hector Berlioz was mightily impressed as he wrote in 1851, “Mr. Gottschalk is one of the very small number of those who possess all the different elements of the sovereign power of the pianist, all the attributes which environ him with an irresistible prestige… his playing strikes from the first, dazzles, astonishes.” Berlioz and other critics were captivated by the syncopated rhythms and characteristic melodies of Gottschalk’s compositions, and his approach to the piano was compared with that of Chopin. A concert tour through Switzerland proved a spectacular success, and by 1851 he came under the patronage of Isabella II of Spain. He reports, “I first played my duo for two pianos, assisted by the King’s pianist. At the finale, I heard her Majesty rise, leave her seat, and place herself behind my chair. The King was to my right, leaning on the piano, the Queen Dowager a little farther off. Several times I could hear the Queen exclaim in Spanish, I never heard anything so beautiful!” Gottschalk stayed nearly 18 months at the Spanish court, and his compositions from that time utilize distinctive Spanish harmonies and rhythms.

Even Hector Berlioz was mightily impressed as he wrote in 1851, “Mr. Gottschalk is one of the very small number of those who possess all the different elements of the sovereign power of the pianist, all the attributes which environ him with an irresistible prestige… his playing strikes from the first, dazzles, astonishes.” Berlioz and other critics were captivated by the syncopated rhythms and characteristic melodies of Gottschalk’s compositions, and his approach to the piano was compared with that of Chopin. A concert tour through Switzerland proved a spectacular success, and by 1851 he came under the patronage of Isabella II of Spain. He reports, “I first played my duo for two pianos, assisted by the King’s pianist. At the finale, I heard her Majesty rise, leave her seat, and place herself behind my chair. The King was to my right, leaning on the piano, the Queen Dowager a little farther off. Several times I could hear the Queen exclaim in Spanish, I never heard anything so beautiful!” Gottschalk stayed nearly 18 months at the Spanish court, and his compositions from that time utilize distinctive Spanish harmonies and rhythms.

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Souvenirs d’Andalousie, Op. 22

Gottschalk had high hopes that his successes in Europe would seamlessly transfer into the United States. He arrived in New York on 10 January 1853 and gave a number of concerts in the following months. However, forced to support his young brother and sisters, he increased the number of concert appearances, and extensively toured the country for three years. Unable to repeat his European triumphs and disappointed by the lukewarm reception back home, Gottschalk set sail for Cuba and the Caribbean in February 1857. Gottschalk had previously visited Cuba, and concerts in Havana were followed by appearances at the island of St. Thomas, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and British Guiana. At times, he completely disappeared from the public’s eye and sequestered himself in remote locations, as he writes, “Then, seized with a profound disgust of the world and of myself, tired, discouraged, suspecting men (and women), I hastened to conceal myself in a desert on the extinguished volcano of N — Every evening I moved my piano upon the terrace, and there, in view of the most beautiful scenery in the world, which was bathed by the serene and limpid atmosphere of the tropics, I played, for myself alone, everything that the scene which opened before me inspired— and what a scene!”

Gottschalk had high hopes that his successes in Europe would seamlessly transfer into the United States. He arrived in New York on 10 January 1853 and gave a number of concerts in the following months. However, forced to support his young brother and sisters, he increased the number of concert appearances, and extensively toured the country for three years. Unable to repeat his European triumphs and disappointed by the lukewarm reception back home, Gottschalk set sail for Cuba and the Caribbean in February 1857. Gottschalk had previously visited Cuba, and concerts in Havana were followed by appearances at the island of St. Thomas, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and British Guiana. At times, he completely disappeared from the public’s eye and sequestered himself in remote locations, as he writes, “Then, seized with a profound disgust of the world and of myself, tired, discouraged, suspecting men (and women), I hastened to conceal myself in a desert on the extinguished volcano of N — Every evening I moved my piano upon the terrace, and there, in view of the most beautiful scenery in the world, which was bathed by the serene and limpid atmosphere of the tropics, I played, for myself alone, everything that the scene which opened before me inspired— and what a scene!”

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Symphonie romantique, “La nuit des tropiques”

Persuaded by a sizeable contract, Gottschalk played for American audiences again in 1862. He reports that he traveled 15,000 miles by rail and gave 85 concerts within the span of roughly four months. Gottschalk arrived in California in 1865, but got involved in a scandal that falsely accused him of compromising a student at the Oakland Female Seminary. Forced to escape, he boarded a ship for South America and he would never see the USA again. For the last years of his life, he highly successfully performed in Peru, Chile, Uruguay and Argentina. Gottschalk became an ambassador for Classical music, and he championed public education and a pan-American model of civic life and culture. Gottschalk arrived in Rio de Janeiro in May 1869, but at the age of 40, he died from malaria and appendicitis. While the impact of Gottschalk’s music will be debated for years to come, it is clear that he was an American original. His best music radiates great emotional power, technical mastery and charm.