Jane Stirling – Frédéric Chopin’s student, patroness, caretaker, manager, and legacy-builder – has always lived in the shadows of her piano teacher. And yet she was an integral part of Chopin’s later life and one of the reasons why his legacy still endures today.

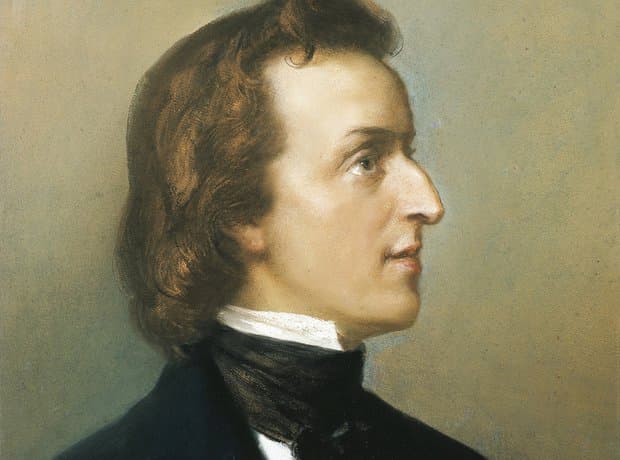

Frédéric Chopin © ClassicFM

Jane Stirling’s Childhood

Jane Wilhelmina Stirling was born 15 July 1804 in Perthshire in central Scotland. She was the daughter of John Stirling of Kippendavie, a wealthy landowner who had property in Scotland and the West Indies, and his wife Mary.

Jane was born into a big family: she had twelve older siblings! Tragically, her mother died when she was a child, and then her father died a few years later. The grieving teenage heiress moved in with her older sister Katharine Erskine, a young and independent widow.

Despite the tragedies of her teenage years, Stirling proved to be a social butterfly. She loved the arts, playing the piano, and going to dances and balls. As the legend goes, over thirty men proposed to her, but she turned them all down because she never fell in love with any of them.

Young Adulthood in Paris

In 1826, when Stirling was twenty-two, her older sister brought her to Paris. The sisters loved the city so much that they began to live part-time in France.

When the time came for Stirling to choose a Parisian piano teacher, she chose Frédéric Chopin, a mutual acquaintance of her former teacher, pianist Lindsay Sloper. Chopin and Stirling became friends. Chopin respected her and her musicianship enough to pass along one of his students to her, and in 1844, she was thrilled to find out that he dedicated two nocturnes to her (the pair in his op. 55).

Ivo Pogorelich Plays Chopin’s Nocturne Op.55 No.2 in E-flat Major

At the time, Chopin was in the midst of an unraveling relationship with author George Sand, and he was trying to come to grips with his new lifestyle. Stirling wanted to help. So they came to an unconventional arrangement: Stirling would serve as a kind of agent and business manager to help keep Chopin’s life running smoothly. She even took on arranging his concerts and worked with him on assembling the French-bound volumes of his works.

George Sand’s daughter wrote about Stirling and Erskine:

“During lessons, when you visited the Master you could meet two tall persons, typical Scottish women, skinny, pale, in indefinite age, serious, dressed in black, never smiling. Under this quite gloomy appearance, there were lofty, noble, and devoted hearts.”

Chopin’s Helper

Stirling seems to have been rather omnipotent in Chopin’s life during this time. She saw to all of the details of his famous Salle Pleyel concert in February 1848, down to the temperature of the auditorium and the choice of flowers. He played a Mozart piano trio, his cello sonata, and some relatively undemanding pieces for solo piano. After the concert was done, he staggered backstage to Stirling and collapsed in her arms. It would be his last Paris concert. In March, revolution broke out, and many of Chopin’s aristocratic supporters fled the country.

A couple of months later, Stirling arranged for him to visit London. Chopin dreaded the rigors of traveling, but he needed the money badly, so in the spring of 1848, they set off together.

Sol Gabetta and Nelson Goerner Play Chopin’s Cello Sonata in G Minor, Op. 65

Chopin’s Last Tour – And a Proposal?

Chopin’s Pleyel grand piano, 1848 (The Cobbe Collection, UK)

While in London, Chopin ended up keeping three pianos in his room from three different makers. His furious landlord doubled the rent, but Stirling stepped in to cover the cost for him. The social highlight of this English visit came when he performed for Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert at a private party.

After the stay in London, he took the train to Edinburgh, per Stirling’s suggestion. He played in Manchester, Glasgow, and Edinburgh. Tickets were expensive – and Jane purchased many of them herself, then gave them away for free. Ominously, while Chopin was in Edinburgh, feeling that he would not live much longer, he drew up a will.

Rumors swirled of an impending engagement between the sick man and his energetic promoter, but Chopin never made a formal offer of marriage. Something about Stirling grew to irritate him – maybe his growing weakness and his increasing dependence on both her and her sister. He wrote things to friends like “A rich woman needs a rich husband” and “They have married me to Miss Stirling; she might as well marry death.” The sisters’ enthusiastic promotion of Protestantism was also proving to be extremely grating.

Chopin’s Death and Its Aftermath

In November 1848, Chopin left the gloomy British Isles to return to Paris. He was deeply in debt, and Stirling quietly paid those debts off. His condition only deteriorated. Over the course of 1849, it became clear that Chopin’s death was imminent. After much suffering, in October he passed away from what is generally believed to have been tuberculosis.

Chopin’s death mask © Wikipedia

After he died, Stirling dressed in mourning black, as if her husband had passed away. She paid the cost of his extravagant funeral at Paris’ famous La Madeleine (although Chopin’s sister Ludwika eventually paid back the cost), and it was attended by thousands. Fearing unscrupulous thieves or souvenir hunters, it is believed by historians that she was likely the anonymous buyer who purchased much of Chopin’s estate, including his famous death mask, to distribute to those who loved him. She also saw that his preserved heart would be brought from Paris to Warsaw.

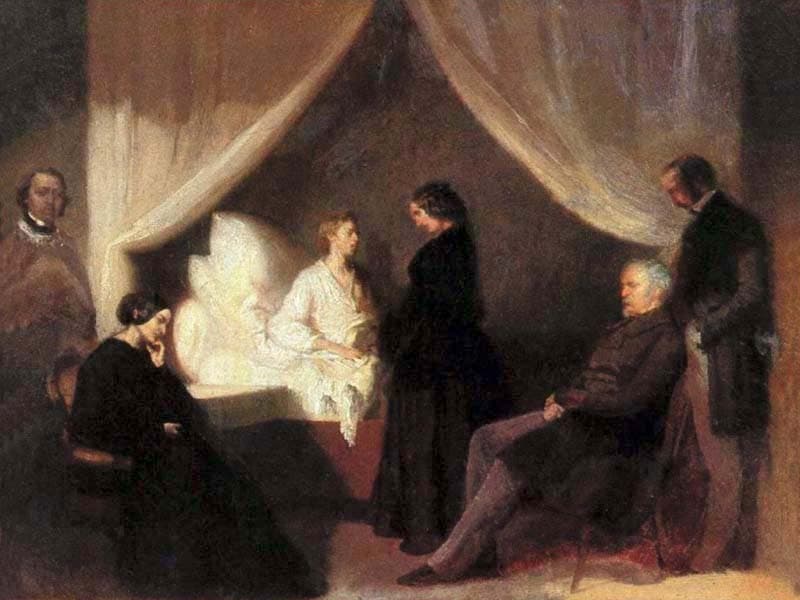

A portrait she’d commissioned of Chopin by Polish artist Teofil Kwiatkowski turned into a deathbed portrait. Pictured in the portrait is Chopin, dressed in white, and surrounded by the dark-clothed figures of author Aleksander Jełowicki, Chopin’s sister Ludwika, piano student Marcelina Czartoryska, Polish politician Wojciech Grzymała, and the artist. Stirling is nowhere to be found: she’s already slipping into the background of the historical record.

Chopin on His Deathbed, by Kwiatkowski, 1849, commissioned by Jane Stirling.

To mark the first anniversary of his death, Stirling wrote to Ludwika asking for a handful of Polish soil so that she could sprinkle it on Chopin’s grave. The request was granted. In a particularly moving gesture, Stirling paid to have one of Chopin’s pianos shipped to Ludwika, and the two women carried on a considerable correspondence after his death, tending to matters of his legacy.

Intriguingly, according to legend, Chopin told Stirling – and Stirling alone – his true date of birth. She is said to have written it down, placed it in a box, and buried it with him.

Stirling’s Post-Chopin Life and Legacy

Stirling lived for another decade after Chopin’s death and died of an ovarian cyst in 1859. She never married. She left most of Chopin’s estate to his mother. It ended up in a palace in Warsaw, where it was destroyed by Russian troops in 1861.

Jane Stirling may not be nearly as famous as Chopin’s other caretaker figure, George Sand, but she was certainly one of his most faithful friends and one of the people we have to thank today for helping to preserve the rich musical legacy that her friend and teacher left behind.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter