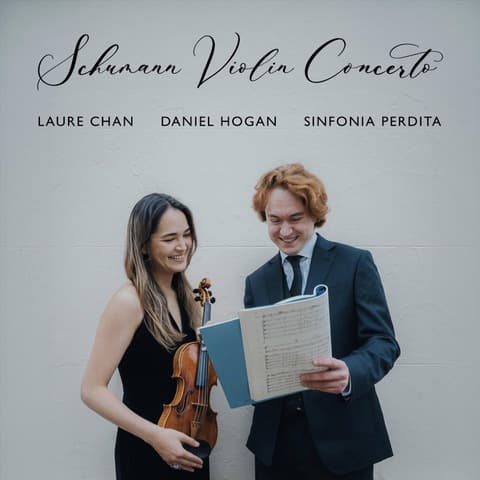

Meet Laure Chan, a young and talented composer and violinist whose album playing with Sinfonia Perdita has recently been released. In this interview, Laure tells us her background and how she became a violinist. She also tells us about the two pieces featured in the album- a Violin Concerto by Schumann and her composition, Lost in Translation.

Laure Chan © John Davis 2020

Hi Laure. Would you like to introduce yourself to our readers? How did you start playing the violin?

I’m Laure Chan. I’m a violinist based in London. I’m of French and Chinese descent, and I’m British as well, and I grew up in London my whole life. I was raised here. My father is Chinese, and my mother is French. I have a very international family, including families in the US, the UK, Asia, and France. I’m not actually from a musical family. Neither of my parents were musicians, but my mother really loved classical music growing up. She didn’t have the opportunity to learn an instrument, nor did my dad have the opportunity to learn it. My mum, especially, was really hoping that her children could have the opportunity. I have two sisters and one brother. They all took instrumental classes growing up, but they didn’t have the same passion and drive to continue practicing it, so it was something they took up as a hobby, and then they moved on to other things. I am the youngest of all my siblings. When I was four, my mom enrolled me in a string instrument program at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where they have a program called First Strings Experience. It is a program to encourage young children to start at the beginning of a musical instrument, particularly a string instrument. I learned how to read music to sing in groups with other children, and then one year later, when I was 5, I chose the violin. A few years later, I realized that this was what I wanted to do.

That was still very young of you to make such a big decision. What and who inspired you to be a violinist?

I went to a concert by a musical hero of mine, Maxim Vengerov, a Siberian violinist. He was playing a concert in the Barbican in London. This particular concert inspired me, and it was the first time I understood that representation of this was a possibility and that I could do this as a profession. Since I wasn’t raised in a musical family, I didn’t know what it was like to be a professional musician. When I saw this concert, I realized how much I wanted to express my music to an audience. I wanted to share this beautiful experience on stage, which was the turning point when I decided to dedicate my life to it.

Did you also decide whether to be a soloist or a performer playing with the orchestra? Has that changed since then?

I think I decided that I wanted to be a soloist. But I’ve enjoyed doing a variety of things. In fact, during my whole musical education, I’ve done a variety of solo playing, orchestral playing, and playing in groups. It’s important as a musician to do everything because it gives you a full-rounded musical experience, and it’s important to listen to others while playing, even if you’re a soloist. If you’re playing with an orchestra, there are so many other parts going on that you need to communicate with, so the chamber music element is still going on. My focus has been on solo works, but I actively play in orchestras, especially with the Chineke! Orchestra. It celebrates cultural diversity, and so it is also nice to be a part of a community, especially being half Asian myself. I work with them frequently, and we have concerts coming up. We will have a mini tour in Germany in June and July and certain tours each year. Also, we’re based in Southbank Centre in the UK; apart from that, I regularly work with other ensembles and often collaborate with my friends. We create our concerts together, so I greatly enjoy the variety. I’ve also wanted to focus more on writing music in the last few years. This is another thing that, as a kid, I enjoyed, but I didn’t consider I would become a composer. Now, I call myself more a performer and a composer rather than categorizing as a soloist, chamber musician, or orchestral musician. I do a variety of everything, really, and I enjoy it.

Your new album features Schumann’s Violin Concerto and your composition, Lost in Translation. Both pieces seem to carry the same theme: heartbreak. Would you like to tell us a bit more about each piece?

The Schumann violin concerto was neglected for many years after it was written because it was created near the end of Schumann’s life. He was very depressed, and he was contemplating suicide. He had a lot of mental health problems. His partner, Clara Schumann, and his close friend, violinist Joseph Joachim, thought this piece reflected his fragile state at the time. The work was hidden for about 80 years and was later rediscovered. It was then revived by a well-known violinist, Yehudi Menuhin, who claimed it was the missing link of the violin repertoire between other works written by Beethoven and Brahms, which were far more well-known and still are. Since then, it has started to get a little more attention, but it’s still very neglected compared to many other violin concerti. So it’s a piece that my friend and conductor Daniel Hogan really loved. He encouraged me to learn the piece, so this was the intention to record this piece because it’s not being performed very much. We are fortunate to have the opportunity to highlight this work, which we both believe is a great piece of music.

Lost in Translation

Lost in Translation was completed on New Year’s Day of 2023. It was written during difficult times in my personal life. I was dealing with feelings of isolation and heartbreak. I wrote this piece to reflect how I felt then, and it became a pretty deep reflection. It’s almost like a short poem in sound or a short capsule of how I felt then. I only use four chords in the piece. I wanted it to be a very simple, direct form of expression. The repetition of the same chords but in variation reflected this feeling of experiencing a repetition of patterns in my life. There are elements of hope as well, and I would say that is also in Schumann’s Concerto, even though it was written during the moment of suffering in his life. So, this album is all about human expression.

The album was recorded with Sinfonia Perdita under the baton of Daniel Hogan. In the album booklet, you mentioned that your friendship with Hogan began when you were both teenagers. How was your experience collaborating with Hogan and Sinfonia Perdita?

Daniel Hogan

Daniel Hogan and I have known each other since we were teenagers. I believe he was 14, and I was 16 when we were in a composition class. We went to the Royal Academy of Music every Saturday and saw each other there. A few years later, he formed the Watford Youth Sinfonia (he’s from Watford in the UK), where we had our first concert ten years ago. So, this album marks ten years of collaboration on stage, and it’s very special for us to have this kind of mutual anniversary.

Just before the pandemic in 2020, I had my first live concert with the Symphonia Perdita. Hogan formed this orchestra as well. Perdita in Latin and Italian means loss, so the idea for the symphony is to champion neglected works that have been lost in the past. The orchestra comprises a mixture of Conservatory students and full-time professionals. We were lucky to have people like them who are regularly on the concert circuit and a lot of friends of ours as well in the London Conservatoire; it was a really friendly collaborative experience, and it was a very youthful, friendly energy that we were experiencing no sense of ego in the room just enjoyment and the passion for music.

You have a radio show, Classical and Beyond. What made you decide to host a radio show? Do you want to share any memorable moments during the show?

The show was a limited series in 2022, for which I created eight episodes. As a classical music musician and host, I introduced pieces of classical music and had guest artists from my field. I also wanted to showcase a wider repertoire as, being someone from a multicultural background – half Chinese and half French – I’ve been influenced by expanding my cultural horizons and knowledge. So, I interviewed a Chinese traditional folk musician called pipa player Cheng Yu, and she talked to me about traditional Chinese music. I had a violinist called Kala Ramnath who is an expert of the Indian classical tradition, which is very different from Western classical. I also had people from the Western field, including violinist Kerson Leong and Manu Brazo, conductors Daniel Hogan and Peggy Wu. It is a theme in my life at the moment, both as a musician and as a person, that I want to explore something of my cultural roots and beyond the Western classical music tradition. There’s so much influence that comes from these different traditions, and of course, it comes naturally from being of a mixed race and wanting to explore more of both my cultural and musical roots.

Are there any upcoming performances you want to share?

In March, I have two performances that I’m looking for. One has recently just been confirmed for International Women’s Day on the 8th of March. I am going to play live on BBC Radio 3’s In Tune Studios, and I will be playing with two of my friends. I’m also looking forward to representing women composers, including some of my original works and works by many other women composers. And then, on the 14th of March, I have an album launch. It’s an intimate event, but it will be held in London to celebrate the release of the album we’re discussing.

The album is available on all platforms through this link.

Learn more about Laure Chan.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter