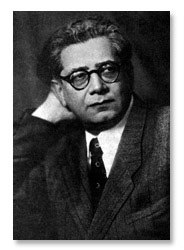

Grigory Ginzburg

© naxos.com

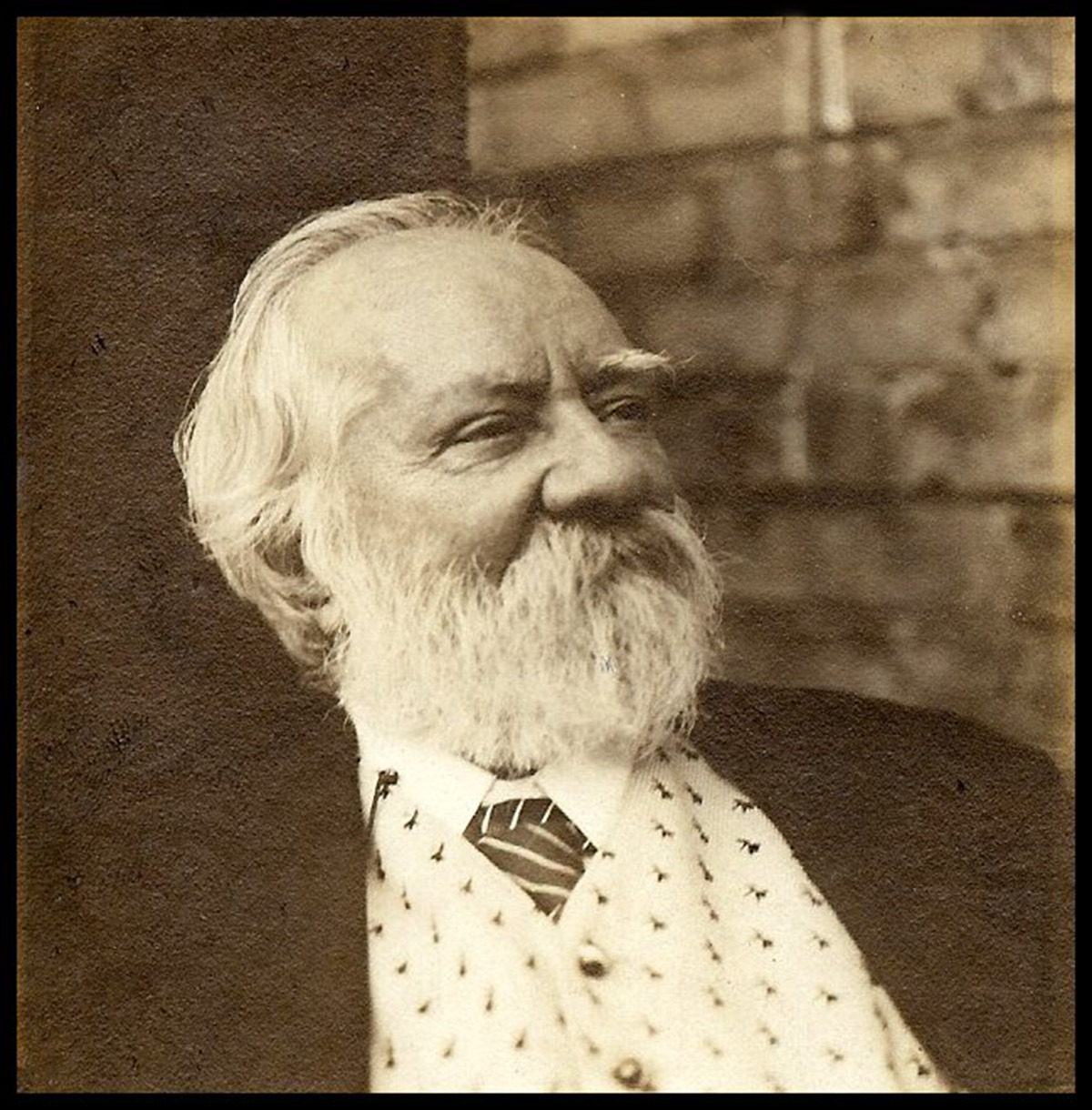

Russian pianist Grigory Ginzburg (1904-1961) and his older brother were the first musicians in their family. His older brother had been studying piano and the young Grigory started by imitating him. At age six, his talent was recognized and in 1917, when he was 13, he became a student of Alexander Goldenweiser at the Moscow Conservatory. He remained close to Goldenweiser his whole life, becoming his assistant after graduation. Ginzburg won the Warsaw International Frederick Chopin Competition in 1927 and returned to the Moscow Conservatory as a professor the next year.

In an interview in in 1946, he talked about his childhood and how he hated practicing – three hours was enough for him. However, in living in Moscow with his teacher and family, he started to understand the value of spending more time in the practice room. He spoke fondly of the hours that he and Goldenweiser spent playing 4-hand repertoire such as Mozart and Beethoven quartets. He also credits Goldenweiser with giving him a meticulousness in his work, noting that he could be called at any time to play an etude (or three on the spot). He also spoke of the terrible emotional crash he felt after graduation, when he went from being a wonderkind to being filled with self-doubt.

He was known for his touch and that is what comes across in his recordings. There’s a delicacy paired with a technical knowledge that takes us deeper into the work.

He was also known for his arrangements of works for piano, doubtlessly inspired by his 4-hand piano work with Goldenweiser.

Rossini: Il barbiere de Siviglia: Largo al factotum; Grigory Ginzburg, piano

In the hands of Yuja Wang, known for her pianistic speed, we hear even more the technical demands that Ginzburg made on his followers.

Rossini: Il barbiere de Siviglia: Largo al factotum; Yuja Wang, piano

In his pianistic repertoire, he, unusually, worked backwards. He began with the Romantics, especially Liszt, and then discovered the world of Beethoven. He said that some composers, such as Rachmaninov, were beyond his comprehension, and therefore beyond his powers.

Ginzberg’s Chopin Op. 25 Etudes are the greatest I know – certainly the equal of Sokolov, Ashkenazy and Pollini – because their elegant virtuosity never obtrudes on the poetry. Like Chopin (though often forgotten) he had an impish sense of humor and never made a pose of his deeper feelings. The relationship with Ginzberg’s more-than-a teacher is one of the most beautiful in music, akin to Haydn and Mozart’s. Thanks for bringing him to wider attention,