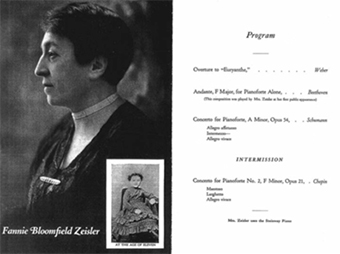

Young Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler on

The Musical News, 1898.

While Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler (1863-1927) is largely forgotten today, her tireless pursuit of excellence and extraordinary gifts as a pianist and teacher made her one of the most significant figures in the classical music world in the early twentieth century. Born in Austria, Zeisler moved to Wisconsin at four years old and later settled in Chicago. Her first piano teacher was her elder brother, Maurice Bloomfield. Fannie’s musical talent was soon discovered, and she caught the public’s attention at eleven years old. She played for Annette Essipoff, who was Theodor Leschetizky’s pupil (and later married to Leschetizky) and Sergei Prokofiev’s teacher. Essipoff recognized Zeisler’s talent immediately and advised her to study with Leschetizky. In 1879, Fannie traveled to Vienna and began five years of intensive study with him at the Vienna Conservatory.

“A Player of Remarkable Promise”

Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler was the first American student of Leschetizky and she was possibly his favorite American student. He complimented her precise and powerful playing as an “electric wonder.” Leschetizky emphasized one’s uniqueness in piano playing and under his instruction, her public performances during her study in Vienna were praised and suggested a very promising performing career.

In 1883, Zeisler finished her study in Vienna and returned to the U.S. The following year she made her debut in Chicago, her brilliant playing was highly praised by newspapers including Boston Music Observer which called Zeisler “a player of remarkable promise.” During this time, she remained devoted to her career; touring and performing even while getting married and becoming pregnant. In 1888, Fannie spent five months studying with Leschetizky again in Vienna, she spent much time at his house where she played with Essipoff and Paderewski, who was also Leschetizky’s student at the time.

Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler performed on the Welter-Mignon reproducing piano in 1908. (From Beth Abelson Macleod’s Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler: The Life and Times of a Piano Virtuoso)

After five months in Vienna, Zeisler returned to the United States where she resumed her extensive performing career. Throughout her career, she appeared with major orchestras almost every season and performed in major cities. Her performance captivated many audiences and music critics. Her powerful and vivid performance was often complimented as powerful as a man. One American critic, William Armstrong, for being commented “she returns to us a finished artist, her technical equipment on a par with contemporary masters of the instrument, and her old fire and fury as fascinating as ever.” During the presidency of Taft, Zeisler was invited to perform at the White House. President Taft later called Zeisler “America’s greatest pianist.”

Ziesler performed extensively during her lifetime, the only recording we have today were recorded on Welter-Mignon reproducing piano and here is one of them:

The Most Conveted Piano Teacher in the United States

A photograph taken during Zeisler’s piano class. (From Beth Abelson Macleod’s

Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler: The Life and Times of a Piano Virtuoso)

In the 1910s, due to deaths in her family and her failing health, Zeisler started performing less and focused on teaching. However, she did not completely stop performing and one of her most remarkable recitals was in 1920. She performed three concertos (Mozart’s C Minor, Chopin’s F Minor, and Tchaikovsky’s B-flat Minor) in a single night. The last public performance was a celebrated performance for her fiftieth anniversary in February 25, 1925. She played two concertos (Schumann A Minor and Chopin F Minor concertos) with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Due to her fame as a concert pianist, Zeisler became one of the most coveted piano teachers in the United States. In 1903, she was appointed the head of the piano department of Bush Temple Conservatory of Music, which later became the Chicago Conservatory College.

As a former student of Leschetizky, Zeisler mentioned that Leschetizky’s teaching method was to have no fixed method but to teach each student according to their individuality. Zeisler learned from him and brought his teaching esthetic to the United States. In Zeisler’s teaching career, she also emphasized each student’s uniqueness and different level of talent. Due to her performance schedule, Zeisler only offered piano class at her home. All her students, as many as thiry students, met at the same time. Each student received individual instruction during the class while the others oberserved and learned from the lessons. Students were taught to play precisely and develop their own character and self-reliance.

Continuing Leschetizky’s Teaching Method

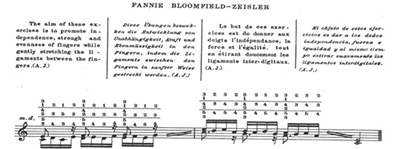

From Master School of Virtuoso Piano Playing, Volume 1, Dover Edition

Similar to Leschetizky, Zeisler was not patient with students playing carelessly and mechanically and she often made harsh and mean comments towards these performances. She once told a student to “go home and tidy up your dresser drawers” as her playing revealed “the habit of slovenliness.” She also told a student that “an electric piano will always excel you if your aim is to be mechanical.”

Even though Leschetizky and Zeisler both emphasized one’s individuality, they both believed in building a solid foundation of piano playing and their students were all assigned to practice different finger exercises. Zeisler required new students to study finger exercises she had prepared before accepting a student on a regular basis.

A Woman Ambassador of Music in the Early Twentieth Century

Program from Zeisler’s with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, February 25, 1925. The caption of the picture said it was Zeisler when she was eleven. (From Beth Abelson Macleod’s Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler: The Life and Times of a Piano Virtuoso)

As the first American student of Leschetizky, Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler presented Leschetizky’s high standards of pianism and became a role model for many young American musicians in the early twentieth century. Zeisler devoted her life to promoting classical music and advancing the music industry. She was a woman ambassador of music for her time. To support female musicians, she wrote and spoke actively about gender and music. She did not accept the insufficient opportunity of female musicians in the music industry. She claimed male and female musicians are equally capable and talented. Zeisler also actively supported her contemporaries and performed their works in her concerts. Female composers of the time, such as Amy Beach, Cecile Chaminade and Marie Prentner dedicated pieces to Zeisler. Zeisler brought classical music to the general public, and often held regular informal concerts in non-traditional settings. In 1927, Zeisler passed away from a heart attack. Her character and achievements are summed up well by her former student, Carol Robinson (1889-1979), who fondly recalled Fannie’s life was full of “lofty idealism, unremitting industry, indomitable energy, and absolute sincerity.”

Born in Hong Kong, Fanny is currently pursuing a doctorate degree of Piano performance and pedagogy at the University of Kansas under the instruction of Dr. Scott McBride Smith. She received her master degrees in Piano Performance and Musicology from the University of Missouri- Kansas City (UMKC). Fanny lives in Kansas City where she maintains a busy performance and teaching schedule. As a musicologist, she has presented her papers at the conferences of the College Music Society (2019), Britain and the World (2019), and the Midwest Music Research Collective (2018).

Born in Hong Kong, Fanny is currently pursuing a doctorate degree of Piano performance and pedagogy at the University of Kansas under the instruction of Dr. Scott McBride Smith. She received her master degrees in Piano Performance and Musicology from the University of Missouri- Kansas City (UMKC). Fanny lives in Kansas City where she maintains a busy performance and teaching schedule. As a musicologist, she has presented her papers at the conferences of the College Music Society (2019), Britain and the World (2019), and the Midwest Music Research Collective (2018).