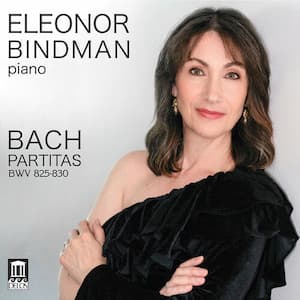

Eleonor Bindman

When I had sufficiently advanced in my piano studies, my teacher introduced me to the “French Suites” by Johann Sebastian Bach. I was told that “Suites” generally consisted of a series of stylized dance movements, with the name of the dance indicated as a title. And thus I learned that the “Allemande,” a French literal translation of the word “German,” is a stately German dance with a meter of 4/4. As I went on to listen to a number of recordings on historical and modern instruments, I was struck by the fact that the tempos seemed to be all over the place. Some interpretations were excruciatingly slow, while most of them sounded like a race to the finish line. When I approached my teacher, I was told that Bach probably used time signatures to convey the basic tempo information, and that genre information, and in some cases Italian tempo words, were used to modify or clarify the tempo implications of time signatures. To tell the truth, that was all rather confusing and I quietly settled on a “slow, moderate or fast” approach for individual movements. From what I have read, the question of tempo in Bach will be debated for a long time to come, but a new release of the Bach Partitas by Eleonor Bindman offers a highly personal and emotional reaction to that basic conundrum.

J.S. Bach: Partita No. 2 in C Minor, BWV 826 – II. Allemande (Eleonor Bindman, piano)

Bindman was born and raised in Riga, Latvia, and started piano lessons at the age of five. After her family emigrated to the United States Bindman continued her studies at NYU and received her MA in piano pedagogy at SUNY, New Paltz under the guidance of Vladimir Feltsman. She has been highly active as a pianist, arranger and teacher, and her recording of her arrangement of the Bach Brandenburg Concertos for Piano Duet with pianist Jenny Lin was declared “breathtaking in its sheer precision and vitality.” Bindman followed up with a multi-volume set of easy and intermediate piano arrangements of Bach’s masterworks, titled “Stepping Stones to Bach.” In 2020 she released her highly successful arrangements of Bach’s Cello Suites for Solo Piano. As a critic wrote, “her experience of working with the complex counterpoint of the Brandenburgs as well as with the expressive possibilities of a single melodic line of the Cello Suites is bound to result in some fresh interpretive insights.” Those insights have now been applied to Bach’s six keyboard Partitas, “long regarded as one of the most important milestones of the Baroque keyboard repertoire. They remain amongst Bach’s most popular works for pianists and listeners alike, with their wealth of invention, drama, intimacy, wit and emotion.”

Bindman was born and raised in Riga, Latvia, and started piano lessons at the age of five. After her family emigrated to the United States Bindman continued her studies at NYU and received her MA in piano pedagogy at SUNY, New Paltz under the guidance of Vladimir Feltsman. She has been highly active as a pianist, arranger and teacher, and her recording of her arrangement of the Bach Brandenburg Concertos for Piano Duet with pianist Jenny Lin was declared “breathtaking in its sheer precision and vitality.” Bindman followed up with a multi-volume set of easy and intermediate piano arrangements of Bach’s masterworks, titled “Stepping Stones to Bach.” In 2020 she released her highly successful arrangements of Bach’s Cello Suites for Solo Piano. As a critic wrote, “her experience of working with the complex counterpoint of the Brandenburgs as well as with the expressive possibilities of a single melodic line of the Cello Suites is bound to result in some fresh interpretive insights.” Those insights have now been applied to Bach’s six keyboard Partitas, “long regarded as one of the most important milestones of the Baroque keyboard repertoire. They remain amongst Bach’s most popular works for pianists and listeners alike, with their wealth of invention, drama, intimacy, wit and emotion.”

J.S. Bach: Cello Suite No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1009 (arr. E. Bindman for piano) – I. Prelude (Eleonor Bindman, piano)

In her Partita recording, Bindman is aiming to “allow listeners the opportunity to enjoy the emotional connotations of rhythm, harmony, counterpoint and ornamentation, and experience the creative treatment of repeats.” She explains, “I find the variety of keys and the character (largely implied by the opening movements of course) of each suite gratifying. I also believe that the Partitas, as an oeuvre, include some of Bach’s most diverse, ingenious and intimate writing for the keyboard (aside from the Well-Tempered Clavier to an extent, of course). They deserve a lot more attention than the Goldbergs, in my humble opinion. Rather than a series of exercises in canons, they are in fact a kaleidoscopic representation of Bach’s genius.” Listening to the recording, I was immediately impressed by Bindman’s relaxed tempos, and the unhurried pace of her interpretation. For one, it allowed Bach’s ornamentations to shine with unheard clarity. Ornamentation is really a terrible word, as it implies that the melody is in need of embellishment in order to be fully understood. In Bindman’s recording, ornamentations become what they should be, an emotional emphasis of the moment. And that is certainly the case in her creative treatment of repeats, when the first sounding is simplified while the repeat presents the richly embellished original.

In her Partita recording, Bindman is aiming to “allow listeners the opportunity to enjoy the emotional connotations of rhythm, harmony, counterpoint and ornamentation, and experience the creative treatment of repeats.” She explains, “I find the variety of keys and the character (largely implied by the opening movements of course) of each suite gratifying. I also believe that the Partitas, as an oeuvre, include some of Bach’s most diverse, ingenious and intimate writing for the keyboard (aside from the Well-Tempered Clavier to an extent, of course). They deserve a lot more attention than the Goldbergs, in my humble opinion. Rather than a series of exercises in canons, they are in fact a kaleidoscopic representation of Bach’s genius.” Listening to the recording, I was immediately impressed by Bindman’s relaxed tempos, and the unhurried pace of her interpretation. For one, it allowed Bach’s ornamentations to shine with unheard clarity. Ornamentation is really a terrible word, as it implies that the melody is in need of embellishment in order to be fully understood. In Bindman’s recording, ornamentations become what they should be, an emotional emphasis of the moment. And that is certainly the case in her creative treatment of repeats, when the first sounding is simplified while the repeat presents the richly embellished original.

J.S. Bach: Partita No. 5 in G Major, BWV 829 – IV. Sarabande (Eleonor Bindman, piano)

Yet, with all that emotional emphasis on the moment I often lost the sense of melodic direction, and the musical pacing frequently made it difficult to hear the contrapuntal connections and harmonic implications. Maybe, I am not supposed to hear them in the first place as Bindman places her recording within the context of current streaming trends. As she writes, “the pastime of listening to music no longer demands our exclusive attention. Current streaming trends “conveniently” split up Classical works and then assign sections to playlists for various designated lifestyle activities.” Personally, I find Bindman’s “urbane approach,” as critics have called it, contradictory. Why go through such great lengths of introducing the listener to the drama, intimacy and emotion of Bach’s music, or as Bindman calls it “a free-flowing and passionate narrative,” when ultimately, it serves as musical wallpaper to painting ones toenails? The one thing to take away from Bindman’s recording, nevertheless, is the realisation that there is no single correct tempo when it comes to the glorious music of Bach.

Yet, with all that emotional emphasis on the moment I often lost the sense of melodic direction, and the musical pacing frequently made it difficult to hear the contrapuntal connections and harmonic implications. Maybe, I am not supposed to hear them in the first place as Bindman places her recording within the context of current streaming trends. As she writes, “the pastime of listening to music no longer demands our exclusive attention. Current streaming trends “conveniently” split up Classical works and then assign sections to playlists for various designated lifestyle activities.” Personally, I find Bindman’s “urbane approach,” as critics have called it, contradictory. Why go through such great lengths of introducing the listener to the drama, intimacy and emotion of Bach’s music, or as Bindman calls it “a free-flowing and passionate narrative,” when ultimately, it serves as musical wallpaper to painting ones toenails? The one thing to take away from Bindman’s recording, nevertheless, is the realisation that there is no single correct tempo when it comes to the glorious music of Bach.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: Le tombeau de Couperin (version for orchestra) – No. 1. Prélude (Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra; Dimitri Mitropoulos, cond.)