Let’s continue to explore Edvard Grieg’s social circle. Christian Emil Horneman (1840-1906) was a Danish composer, conductor, and music publisher. Born in Copenhagen, he made his way to Leipzig to study at the Conservatory. That’s where he met his fellow student Edvard Grieg, and they developed “a close and long but at times turbulent friendship.”

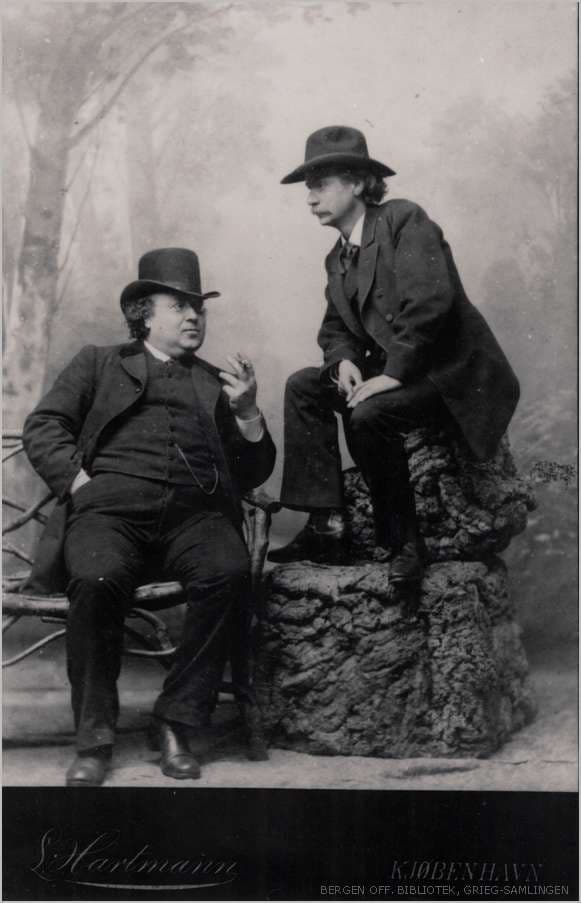

Edvard Grieg and Christian Emil Horneman

Grieg described him as an “ingenious fellow student, a wild, uncontrollable comrade with a bright head and a warm heart.” Once they had finished their studies, they started the music company “Euterpe” in 1865 with the principal aim of creating a forum for new Scandinavian music. “Euterpe” folded after a couple of years, but in 1871 Horneman took the initiative to start the “Nordic Music Magazine,” and he enlisted the Swedish composer August Söderman and also Edvard Grieg. The Magazine was published for only three years, and it dissolved amongst bitter reproaches and petty squabbles. Horneman was a close friend, but he was also a music publisher, and he had a great interest in Grieg’s music. In all, Grieg composed 66 “Lyric Pieces,” and he once wrote to Horneman, “I honestly haven’t done anything, other than the so-called ‘Lyrical Pieces’ which are surrounding me like lice and fleas in the country.”

Edvard Grieg: Lyric Pieces, Op. 12 (Marián Lapšanský, piano)

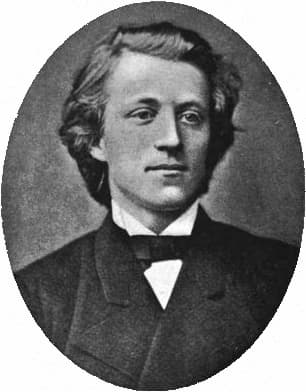

John Paulsen

The name John Paulsen is very rarely mentioned in books on Norwegian literature. Regarded as a minor poet, he was a friend of Edvard Grieg from their early days in Bergen. They traveled together to Bayreuth for the first Wagner festival and listened to a performance of the entire Ring cycle. Grieg described it as “the most remarkable work of our whole cultural history.” Grieg considered Paulsen a very close friend, and they copiously exchanged letters. Grieg wrote to Paulsen in 1876, “There is nothing nicer than a friend’s letter! My imagination is rarely in such a stir as when I wrote to a friend! And you are such a one to me. I feel that while I sit here writing. Not because I start the letter with: Dear Friend!—but because you are what you are.” In all, Grieg set 17 of Paulsen’s poetry, but critics suggest, “he selected Paulsen’s poem for the sake of their friendship rather than from any artist motives.” Once he had completed the Op. 26 songs, Grieg wrote, “In you, I see so much of myself from earlier days. Therefore, I can say to you, acquire steel, steel, steel!”

Edvard Grieg: 5 Songs, Op. 26 (Hilde Haraldsen Sveen, soprano; Signe Bakke, piano)

Edvard Grieg and Nina Hagerup © Grieg Museum

Nina Hagerup (1845-1935) was born in Bergen, and her mother—an actress of Danish origin—was a sister of Gesine Grieg, the mother of Edvard Grieg. Edvard was roughly 2 years older, and the children knew each other from an early age. Eventually, the Hagerup family moved to Copenhagen and Edvard went to Leipzig for his studies. Grieg came to Copenhagen in 1863 and the cousins met again. Nina had taken vocal lessons, and they met frequently to make music. Around Christmas time in 1864, Grieg confessed his love, but both families rejected the engagement. Nina’s mother wrote, “he is nothing and he has nothing and he writes music that nobody wants to hear.” It took both sets of parents the better part of a year before they finally gave permission to announce the engagement. In the event, Nina Hagerup and Edvard Grieg married in Copenhagen on 11 June 1867, in the absence of both sets of parents. Initially, Edvard earned income from giving piano lessons and Nina worked as a singing teacher. Nina was always highly supportive of Edvard’s work, and she became his musical partner, artistic advisor and assistant. In turn, Edvard regarded her as his best interpreter of his music, and according to a diary entry from 1905 even as the “only true interpreter” of his songs.

Edvard Grieg: Romancer og Sange, Op. 18 (Monica Groop, mezzo-soprano; Roger Vignoles, piano)

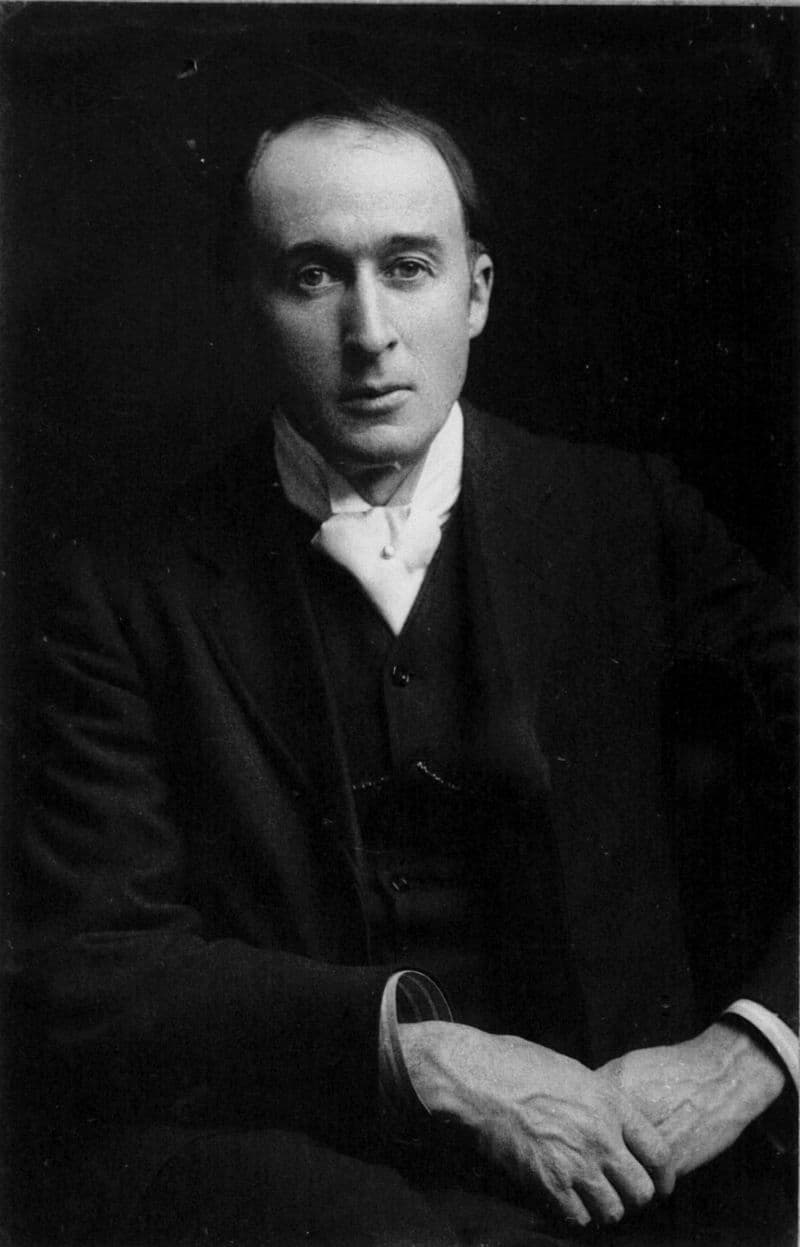

Frederick Delius

Introduced by the Norwegian composer Christian Sinding, Frederick Delius (1862-1934) first met Edvard Grieg in Leipzig in 1887. Delius writes after this first meeting, “I was very proud of having made his acquaintance, for since I was a little boy I had loved his music. I had as a child always been accustomed to Mozart and Beethoven and when I first heard Grieg it was as if a breath of mountain air had come to me.” Grieg, in turn, recognized Delius’s potential and became a warm supporter of the young composer. Furthermore, at a dinner party in London, Grieg finally convinced Julius Delius that his son’s future lay in music. Grieg played an important role in the young composer’s education, as he found his primary inspiration in nature and in folk-melodies. Early in his career Delius had drawn inspiration from Chopin, but now “he lightened the Wagnerian load by imitating Grieg’s airy texture and none-developing use of chromaticism.” Additionally, Delius always was supremely interested in Norway. “Throughout his life he was drawn to Norway’s breathtaking landscape, its literature, its art and the character of its people.”

Edvard Grieg: Norwegian Dances, Op. 35 (Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Ludvig Baron Holberg, 1752

Edvard Grieg was born in the city of Bergen, a town surrounded by mountains and fjords. As a trading post, the settlement was first mentioned in 1021, and in time it became Norway’s largest city. This changed only in 1830 when Bergen was overtaken by the capital Christiania, today known as Oslo. However, Grieg was not the only famous son born in Bergen, and in 1884 the city organized the celebration of the bicentennial of the birth of the “Moliere of the North,” Norwegian writer Ludvig Baron Holberg (1684-1754). A near contemporary of J.S. Bach, Holberg was professor of Metaphysics, Latin, Literature and History at the University of Copenhagen. But he was also an acclaimed writer of comedies and satire greatly influenced by Voltaire. For the bicentennial celebration, Grieg was commissioned to provide some music, and the composer selected the form of a French Baroque Suite. Grieg called the work “my powdered-wig piece,” and it was first issued for piano solo.

Edvard Grieg: From Holberg’s Time, Op. 40 (Einar Steen-Nøkleberg, piano)

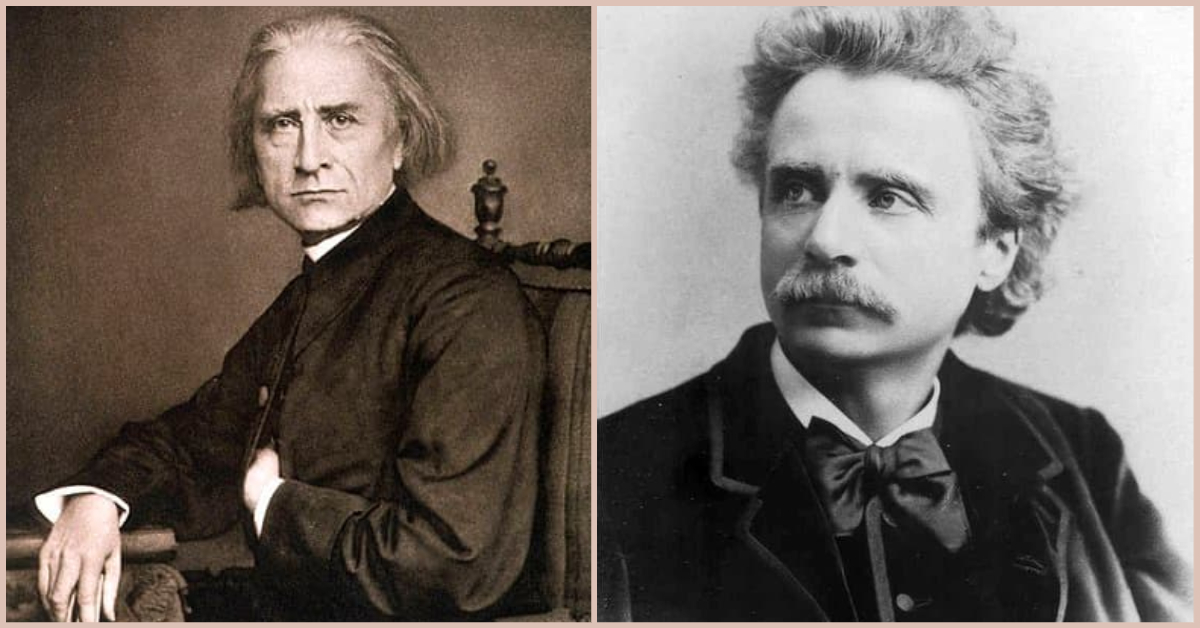

Franz Liszt and Edvard Grieg

Out of the blue, Edvard Grieg received a letter from Franz Liszt in 1868. Grieg had not yet met Liszt, and he was clearly astounded that Liszt was praising his Sonata for violin and piano. Grieg presented the Liszt letter to the Parliament of Norway, and they quickly granted him a yearly pension to devote his time to compositions. That money also financed a two-day trip to Rome to finally meet with Liszt. On the first day Liszt played the sonata for violin and piano, both parts at once. Grieg watched intently as Liszt didn’t miss a single note and “brought out the full quality of the violin.” On the second day of his visit, Grieg presented Liszt with the manuscript of the piano concerto, which had been refused by a publisher. When Liszt invited Grieg to play the work, Grieg declines saying that “he had not practiced it.” As such Liszt sat down at the piano, and told Grieg that he also hadn’t practiced it. Grieg wrote, “Liszt read the concerto at sight, at so fast a tempo that I had to slow him down. He played with such ease that he had time to make comments upon it, brilliant remarks about his comprehension of it as he played.” Liszt remained highly supportive, and on hearing Grieg’s string quartet No. 1 he wrote, “It is a long time since I have encountered a new composition, especially a string quartet, which has intrigue me as greatly as this distinctive and admirable work by Grieg.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Edvard Grieg: String Quartet, Op. 27