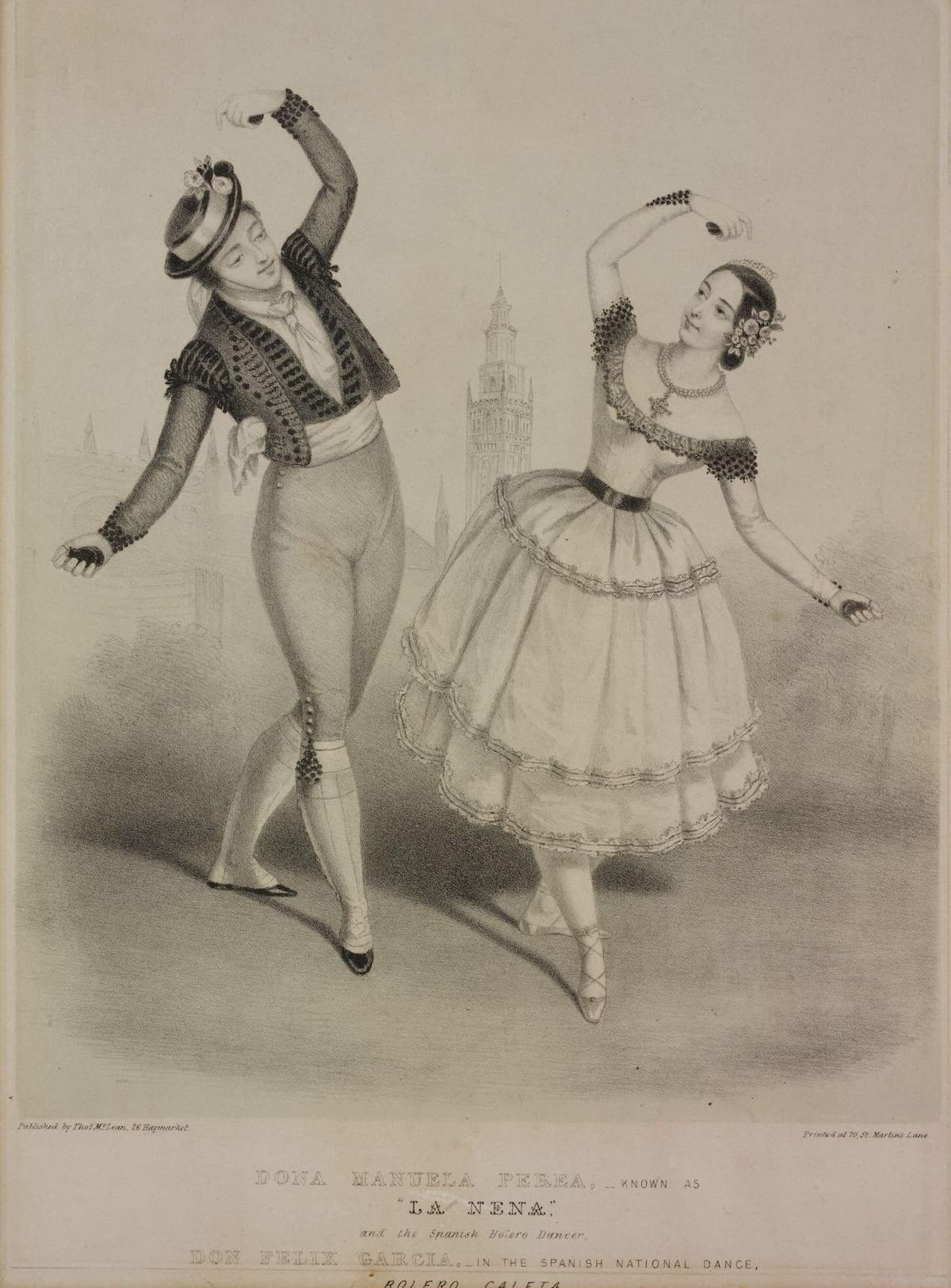

Although to many people the Bolero is a work for orchestra by Maurice Ravel, or, perhaps, a short jacket imitating a matador’s short jacket, the bolero is also a dance. Coming out of Spain in the late 18th century, the dance is an imitation of the movements made by the toreador in a bullfight, while his partner alternates between movements suggestive of the bull or the matador’s cape.

Dona Manuela Perera, known as / “La Nena,” / and the Spanish Bolero Dancer, /

Don Felix Garcia, in the Spanish National Dance, / Bolero Caleta, 1850s (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Dona Manuela Perera was known as “La Nena” (The Baby) because she was so small. She danced in London in the mid-19th century.

The dance is in sections, starting with the paseo, where the dancers come onto the dance floor; the traversa, a “crossing” done both before and after the following step; the differencias – A series of steps made in place that display the grace and balance of the dancers; the finales, where the dancers interact by passing by each other in various ways giving opportunities for flirting and connection and the final bien parado (graceful attitude) where the couple acknowledge the audience and then clasp each other at the waist as a formal salute before leaving the dance floor.

Antonio Cabral Bejarano: A Bolero Dancer, 1842 (Malagà, Spain: Carmen Thyssen Museum)

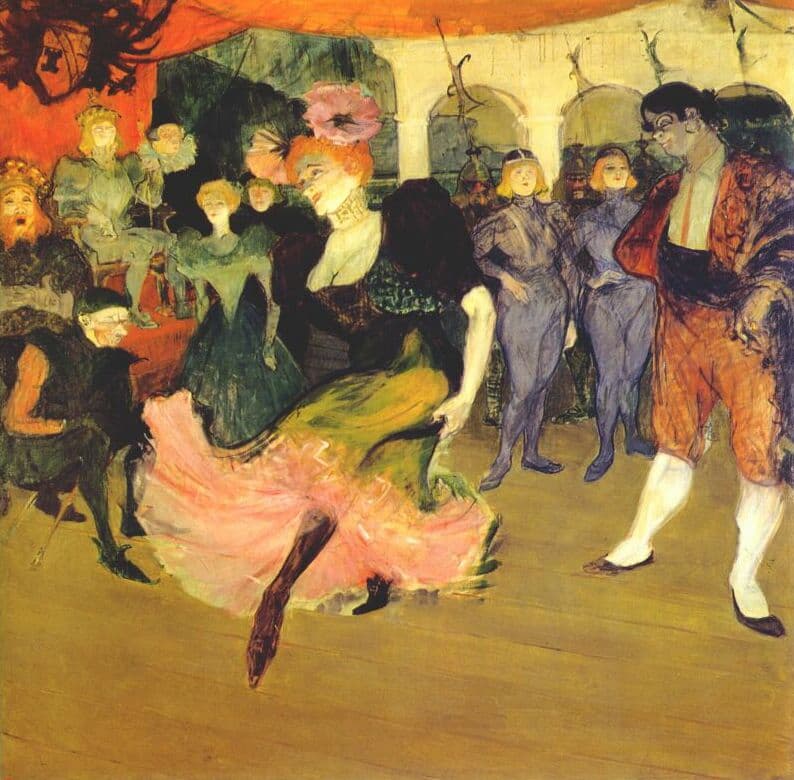

The dance is full of dramatic tension combined with controlled movements that require athletic grace. The French composer and performer Hervé added a bolero into the beginning of the second act of his operetta Chilpéric, given for a 3-month run at the Théâtre des Variétés in 1895. Toulouse-Lautrec attended 20 times, by report, and created this painting of Marcelle Lender dancing the bolero.

Toulouse-Lautrec: Marcelle Lender dancing the Bolero in Hervé’s “Chilperic”, 1895 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art)

This bolero was written by the 19th-century Spanish classical guitarist and composer Julián Arcas. In this work, taken at a moderate tempo, in triple meter, we are given alternating arpeggiated chordal patterns and lyrical themes. The whole style is very traditional.

Julián Arcas: Bolero (Masatomo Tomikawa, guitar)

Although we recognize him primarily for the changes he brought to Polish traditional dances such as the mazurka, Frédéric Chopin also played with other national dances, such as this 1833 bolero. After an expansive introduction, Chopin falls into a lyrical theme in triple meter. The key to the Spanish exoticism is the repeated emphasis on semi-tone intervals. This was a signal in 1830s Europe for the exotic other. Although the various sections of the work can seem quite disparate, Chopin uses a ‘continuously thrumming bolero rhythm’ to bring his elements together.

Frédéric Chopin: Boléro, Op. 19 (Louis Lortie, piano)

In the 20th century, composers such as Enrique Granados (1867-1816) composed boleros, which carry all the theatricality of the bull ring into their setting. In his collection Danzas españolas para piano, his last dance is a bolero. Although the melodies he used are connected with the folk tradition in style, they are all original to Granados.

Enrique Granados: 12 Danzas españolas (Spanish Dances), Op. 37 (arr. R. Ferrer) – No. 12. Bolero (Zambra) (Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia National Orchestra; Salvador Brotons, cond.)

We have to return, in the end, to the most famous bolero. Ravel’s Bolero is in ¾ time, driven by an incessant drum beat. It was a commission by the dancer Ida Rubinstein who originally wanted some orchestrations of piano pieces by Isaac Albeniz. Finding that another composer was already doing these, Ravel settled on writing a new piece. Ravel described the work as an orchestrated crescendo. By focusing solely on the rhythm and the repetition of the insistent melody, Ravel ignored the sections that were part of the original dance.

Maurice Ravel: Bolero (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

The New York premiere of the work was done by Arturo Toscanini with the New York Philharmonic. The work was a rousing success, with shouts and cheers from the audience. However, when Toscanini took the work to Paris on tour, Ravel discovered that Toscanini’s tempo was much faster than he desired and he refused to bow when Toscanini signaled to him in the audience. Toscanini insisted his tempo was the only way to save the piece and if he played it at Ravel’s tempo, the work was not effective. Ravel retorted that then he should not play it. This very public battle between composer and conductor only increased the popularity of the work, which included the 1934 film of the same title, starring George Raft and Carole Lombard.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Raft and Carole Lombard: Bailando Bolero!