In our last blog, we looked at the stories of some unfinished masterpieces being restored. Let us continue our exploration, starting with Mahler’s Symphony No. 10.

Mahler: Symphony 10

In 1910, Gustav Mahler was not a happy man. He had been diagnosed with heart disease, and lost his young daughter Maria Anna to scarlet fever. Meanwhile, his wife Alma had met the young architect Walter Gropius and they soon engaged in a passionate and all-consuming affair. A love letter from Gropius ended up in Mahler’s hands, and the composer sought professional help from Sigmund Freud. During this volatile time of emotional upheaval, Mahler did manage to draft a Tenth Symphony.

Alma and Gustav Mahler, Basel 1903 © Mahler Foundation

Littered with agonizing commentaries on the heart wrenching events of the summer, Mahler envisioned a 5-movement layout, and produced a nearly continuous sketch for the entire work. He did complete the first movement marked “Adagio,” and produced a relatively far-advanced central “Purgatorio” movement. However, a bout of bacterial endocarditis cut short his final artistic statement, and Mahler died in Vienna, on 18 May 1911. For nearly 13 years, Alma Mahler retained the “… precious right to protect as my own the treasure of the Tenth Symphony… But now I feel it my duty to make known the last thoughts of the master.”

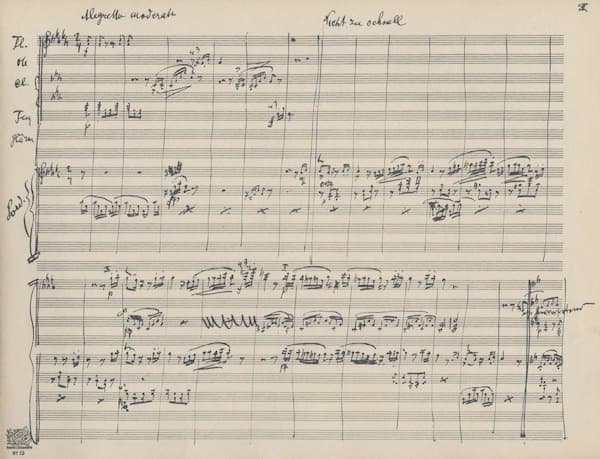

Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 music score

In 1924 Alma published the complete sketches in facsimile, edited by Ernst Krenek. Krenek decided that only the first and third movements could be performed without “paraphrasing upon the ideas of a departed master,” and these movements, with additions by Franz Schalk and Alexander von Zemlinsky, were performed on 12 October 1924. Since then, a number of musicologists have fleshed-out all of Mahler’s sketches, most notably Deryck Cooke, who still had the pleasure of having his version personally banned by Alma Mahler. In a good many performances today, only the opening “Adagio” is given, but the Cooke version has also gained significant traction in the concert hall.

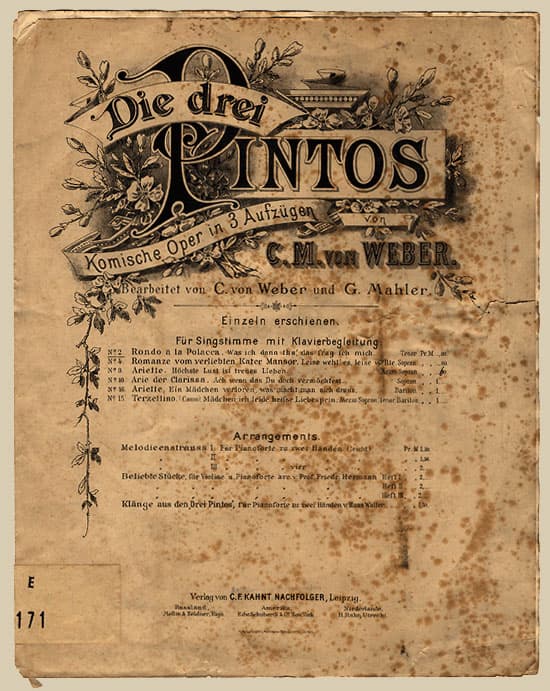

Carl Maria von Weber: Die drei Pintos (completed by Gustav Mahler) “Act III”

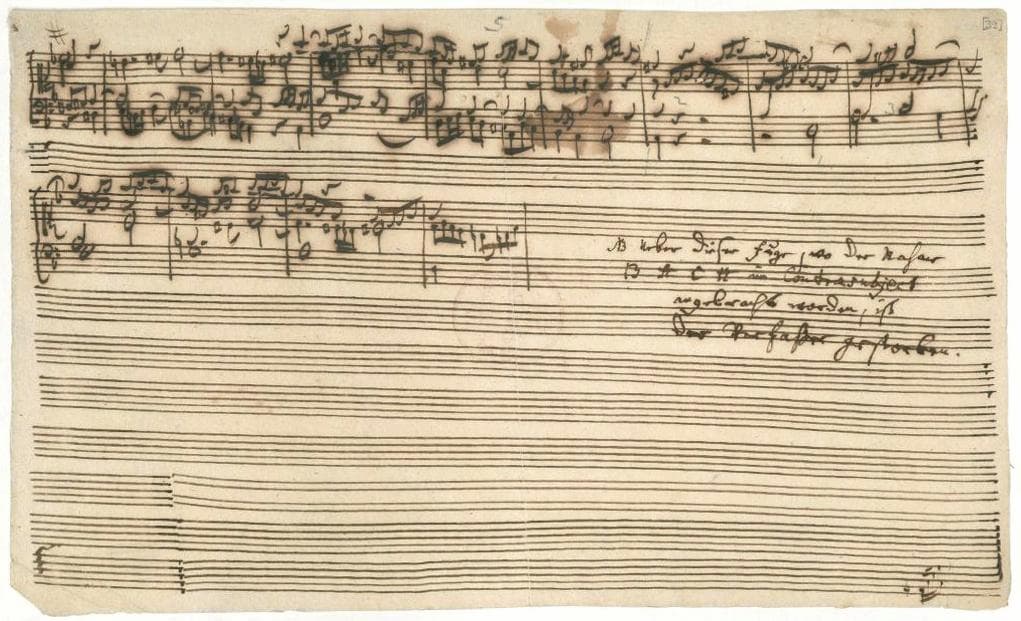

The Three Pintos original score

Carl Maria von Weber: Die drei Pintos (completed by Gustav Mahler) (Robert Holzer, bass-baritone; Peter Furlong, tenor; Barbara Zechmeister, soprano; Sophie Marilley, mezzo-soprano; Eric Shaw, tenor; Alessandro Svab, bass; Stewart Kempster, bass; Sinead Campbell, soprano; Ales Jenis, baritone; Wexford Festival Opera Chorus; Belarussian National Philharmonic Orchestra; Paolo Arrivabeni, cond.)

Talking about Gustav Mahler. After appointments in Bad Hall, Laibach, Iglau, Olmütz, Kassel, and Prague, the aspiring composer was appointed assistant conductor to Arthur Nikisch at the Stadttheater in Leipzig. Once arrived, he met a captain in the Saxon army who turned out to be the grandson of Carl Maria von Weber. Apparently, Carl von Weber was in possession of musical sketches for Die drei Pintos, an unfinished comic opera by his grandfather. Weber’s family had made a number of unsuccessful attempts to have the opera completed, with Giacomo Meyerbeer sitting on the sketches for 26 years. Carl and Gustav quickly agreed to bring the work to completion, and Mahler unscrambled the drafts and provided the instrumentation for the existing fragments. Since 13 musical numbers were needed in addition to the existing 7, Mahler went ahead and composed this music himself, albeit based on Weber’s themes. Mahler conducted the performance of the reconstructed “Three Pintos,” on 20 January 1888 and Tchaikovsky was in the audience. Can you tell which numbers are originally by Weber and which ones Mahler added?

Ernest Chausson: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 35

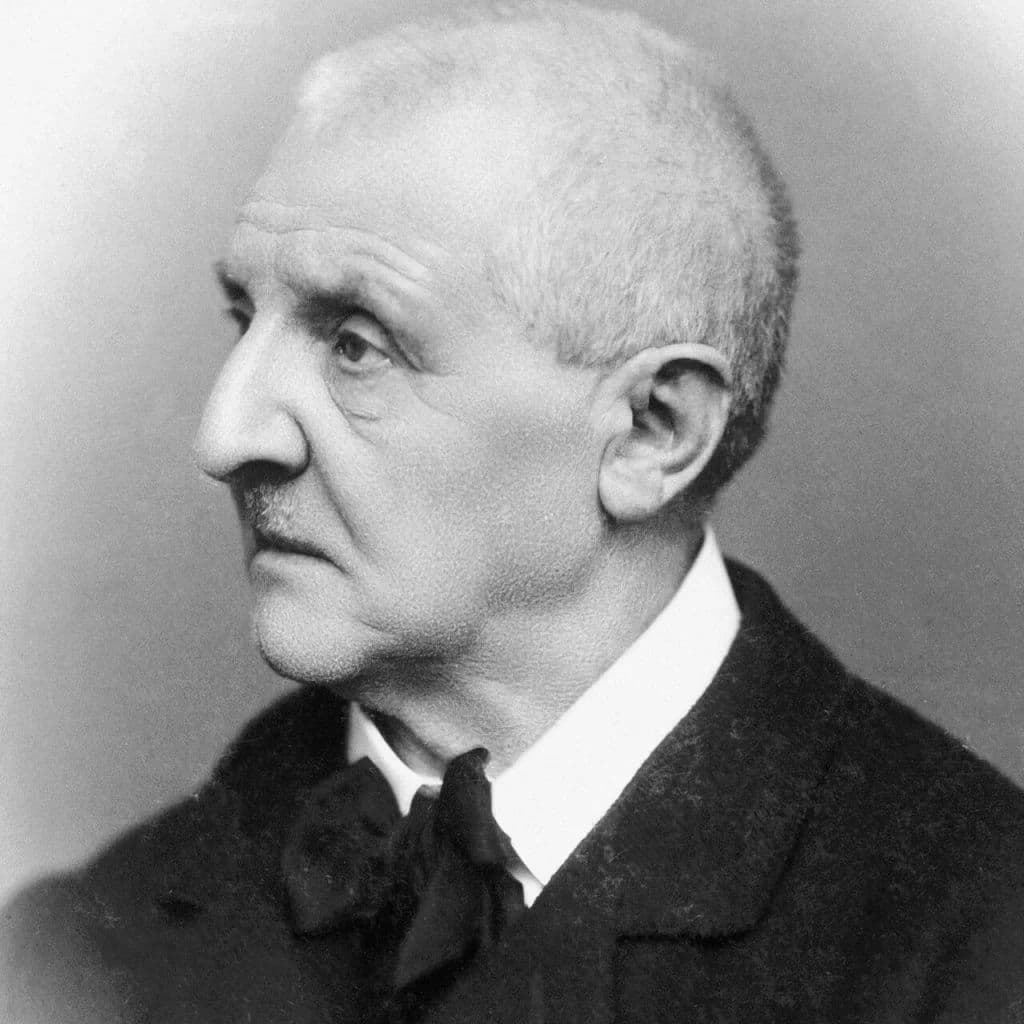

Chausson turning pages for Debussy

Ernest Chausson: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 35 (Ludwig Quartet)

Ernest Chausson wrote in his diary at the age of twenty, “I have the premonition that my life will be short. I’m far from complaining about it, but I should not want to die before having done something.” After some debate about his future direction and leaving behind his career as a barrister, Chausson decided to study music. He attended the Paris Conservatoire and counted Jules Massenet and César Franck among his teachers. He also made a number of pilgrimages to Bayreuth and saw the premiere of Wagner’s Parsifal. The process of composing was always a bit of a struggle for him, and true to his premonition, Chausson died at the age of 44. Riding his bicycle downhill on one of his country retreats in Limay, Yvelines, he hit a brick wall and died instantly on 10 June 1899. The exact circumstances of this tragic accident remain unclear, but at that time he was actively working on a string quartet in C minor. Chausson had fully scored all but part of the third and last movement, and he was writing the last movement on the day of his fatal accident. At the request of Chausson’s family, his good friend Vincent d’Indy completed the final movement and the entire work first sounded on 27 January 1900. Since Chausson had completed the vast majority of the composition, d’Indy simply provided the finishing touches.

Ottorino Respighi: Violin Concerto in A major

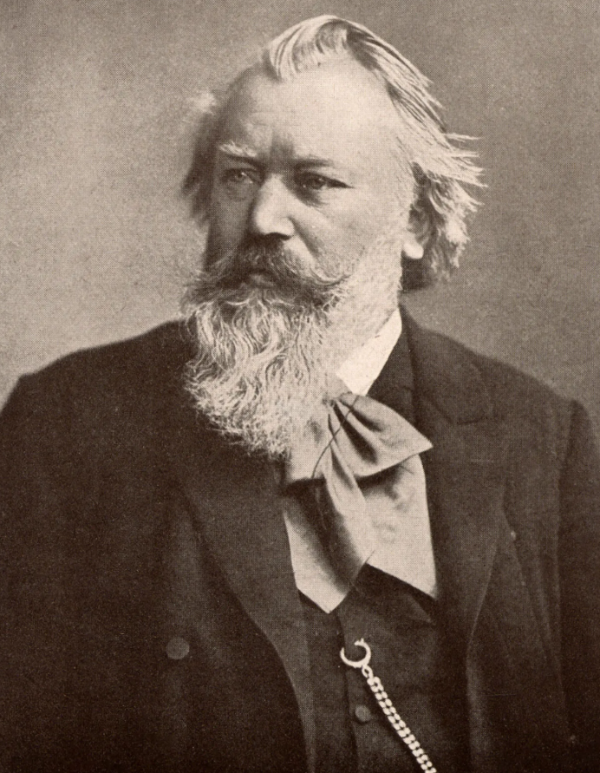

Ottorino Respighi

Ottorino Respighi: Violin Concerto in A major (Laura Marzadori, violin; Chamber Orchestra of New York; Salvatore Di Vittorio, cond.)

Completions of unfinished works seem to be enjoying some popularity these days, and this is clearly understandable. Unless we find some major stashes of yet undiscovered music, the canonic composers really can’t provide us with any more music. As such, the next best step is to complete the unfinished works left behind. Ottorino Respighi left his first violin concerto unfinished. The composer apparently decided in 1903 to focus his attention on other projects. He had completed the first two movements, and scored the introduction of the third movement in piano reduction. Almost one century later, the Respighi estate and the Respighi archive invited Salvatore Di Vittorio to complete the concerto. Di Vittorio went to work and edited the first two movements. He orchestrated the introduction to the third movement, “and then completed the concerto following Respighi’s vision using rondo form.” The work was finished in 2009, and the concerto premiered with the Chamber Orchestra of New York conducted by Di Vittorio. Not everybody was enthusiastic, as “it’s difficult to escape the idea that the bottom of the barrel is being scraped.” That assessment seems a bit harsh, even though it’s terribly difficult to justify anything like Resphighi’s vision.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter