From the Diary of a Hermit

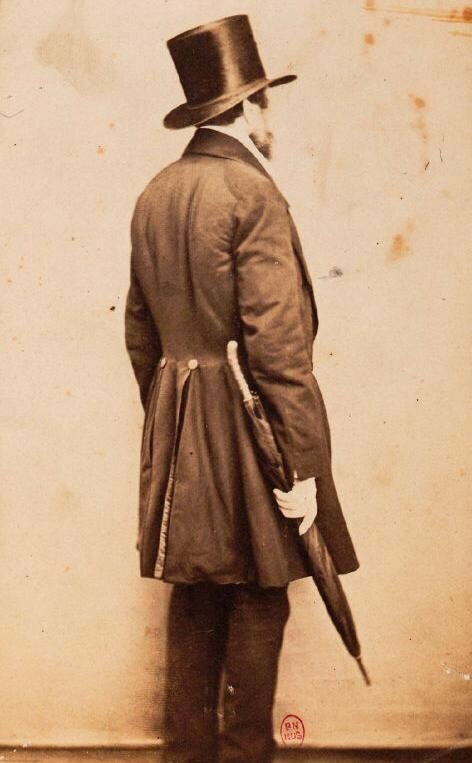

One of two known photographs of the reclusive Alkan, date unknown

At one time or another, Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813-1888) was mentioned in the same breath with Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt and even compared with Hector Berlioz. Not only was Alkan — he was born of Jewish parentage as Charles-Valentin Morhange — one of the most celebrated pianists of the nineteenth century, he was also a most unusual composer, “remarkable in both technique and imagination.” Yet, somewhat surprisingly, he was almost completely ignored by his contemporaries and subsequent generations. Various reasons have been suggested, however, this overall neglect can surely be attributed to his rather enigmatic character. In 1861 Alkan writes to a friend, “I’m becoming daily more and more misanthropic and misogynous… nothing worthwhile, good or useful to do… no one to devote myself to. My situation makes me horribly sad and wretched. Even musical production has lost its attraction for me for I can’t see the point or goal.” Painfully shy and reclusive, and certainly prone to extensive bouts of depression, Alkan withdrew into virtual seclusion for decades on end. It had all started most promising, however; Alkan gave his first public concert as a violinist at age seven.

Charles-Valentin Alkan: Symphony Op. 39 – No. 4 Allegro: Allegro moderato (Bernard Ringeissen, piano)

By that time, he already had been a student at the Paris Conservatoire for almost 2 years, and during his piano audition the examiners reported, “This child has amazing abilities.” By age fourteen, Alkan had composed a set of piano variations on a theme by Daniel Steibelt, published as Opus 1. He soon performed in the leading salons and concert halls of Paris, and made friends with Franz Liszt, Eugène Delacroix, George Sand and Frédéric Chopin. He continued to publish piano music, including the Trois Grandes Etudes, one for the left hand, one for the right hand, and the third for both hands together. Robert Schumann commented on these pieces as follows, “One is startled by such false, such unnatural art…the last piece titled ‘Morte’ is a crabbed waste, overgrown with brush and weeds…nothing is to be found but black on black.” By the age of 25, Alkan had reached the peak of his career, with Franz Liszt providing glowing reviews of his performances and even recommending him for the post of Professor at the Geneva Conservatoire. Regarded as among the principal virtuosos of the day, Alkan suddenly and inexplicably isolated himself for six years from the general musical life of Paris. He briefly reappeared for two concert appearances in 1844 and 1845, but being passed over for a full-time appointment at the Paris Conservatoire saw Alkan isolating himself for the next twenty-five years. He continued to publish music, but he seemed to devote the majority of his time to a complete translation of the Hebrew Talmud and the Syriac version of the New Testament into French. Entirely unexpected, Alkan emerged from his self-imposed isolation in 1873 to play six “Petits Concerts” at the Érard piano showrooms. Surprisingly, he did not perform his own music, but compositions by Bach, Handel, Mendelssohn and Beethoven, among others. Vincent d’Indy, who was in the audience wrote, “I listened, rooted to the spot by the expressive, crystal clear playing…what transpired in the great Beethovenian poem, I can scarcely describe. Above all, the Arioso and the Fugue, where melody, penetrating the mystery of Death itself, climbs to a blaze of light, aroused in me an enthusiasm such as I have never experienced since. This was not Liszt — perhaps less perfect technically — but it had greater intimacy and was more humanly moving.”

Charles-Valentin Morhange (Alkan)

Alkan died on 29 March 1888, with the manner of his death becoming musical lore. The pianist Isidor Philipp reported that a heavy bookcase falling on him caused Alkan’s death, as he was reaching for a volume of the Talmud. Be that as it may, this narrative certainly emphasized Alkan’s deeply religious and literary interests and provided a fitting counterpoint to Liszt’s flamboyant transformation into a tonsured Abbé. While Alkan’s juvenilia imitate the popular convention of composing variations and rondos on operatic melodies, his assorted studies of 1837 and 1838 display the characteristic brilliance and extreme technical difficulties that his oeuvre is known for. Among his most unusual compositions are a Symphony and Concerto for Piano Solo. These works disclose Alkan’s unconventional ideas about tonal structures, which are not bound by a unity of key, complex musical textures, orchestral breath and duration, and feature diabolical challenges for even the most expertly trained pianist. Only recently have a number of private societies and adventurous pianist begun to explore the intensely private musical world of one of the greatest and unusual virtuoso pianists of all times.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter