150 years ago, on 20 October 1874, the leading American composer of art music of the early 20th century, Charles Edward Ives, was born in Danbury, Connecticut. Ives was a unique figure as he remained an amateur throughout his mature, creative life. He wrote music primarily for his own amusement and gratification, and he cultivated a style utterly dissociated from the mainstream. As Robert P. Morgan puts it, “Ives was a quintessential outsider, an American maverick who followed his own idiosyncratic path in pursuit of private artistic goals.”

Charles Ives, ca. 1889

From an early age, Ives mastered three particular musical traditions: American vernacular music, Protestant church music, and European classical music. American popular and nationalist marching band music stood alongside, and sometimes simultaneously, with hymns, choral pieces and folk ballads. With such diverse musical sources at hand, Ives began to experiment with musical techniques, eventually reaching conclusions that would foreshadow musical developments in the 20th century. To celebrate his 150th birthday, we decided to take a closer listen to his 4 Violin Sonatas.

Charles Ives: Violin Sonata No. 1 (Hilary Hahn, violin; Valentina Lisitsa, piano)

Violin Sonata No. 1

Charles Ives’ Violin Sonata No. 1

Between 1902 and 1916, Charles Ives composed four sonatas for violin and piano. As H. Wiley Hitchcock writes, “these sonatas all seem to be citizens of the same musical world. Each had three movements; each includes one or more movements in cumulative musical form; each is tinged with the music of American Protestant hymnody and ends with a finale based on a hymn tune; and all are comparatively easy pieces by Ives’ standards.”

The majority of movements use something called “cumulative form.” That particular term was coined by scholar J. Peter Burkholder, and it describes a musical process that reverses the progression of traditional sonata form. It means that movements start with a suggestion of musical fragments that hint at a preexisting melody. As the movement climaxes, that borrowed melody sounds fully formed in its simple entirety.

Origins

Charles Ives, n.d.

In his “Memos”, Ives relates the somewhat tortured origins of the First Sonata. He explains, “this sonata was written in 1903 and 1908. I remember starting the first theme just the first Sunday after I gave up playing in church. In some places, it is a kind of retrogression, but on the other hand, there are things in it, rhythmically, harmonically, and structurally which Mr. E. Robert Schmitz told me last year (1931) he didn’t remember (even up to the present time) seeing in other music.

Mr. Schmitz apparently met Darius Milhaud in 1927, and he told him that he noticed in my score many things that he’d never seen before in any other music. What they were or what he had in mind, except in a general way, I don’t know. If it weren’t for the tiresome, easy, blab way so many (mostly Americans) say that all American modern music is just taken after the modern Europeans, of whom Milhaud is often mentioned.”

Picturesque Hymnody

Ives described his First Sonata as a kind of reflection and remembrance of people gathering outdoors, in which men got up and said what they thought, regardless of consequences. In terms of musical language, the work is “a kind of mixture between the older way of writing and the newer ways.” The harmonic language is rather dense but mostly tonal, with some new sonorities introduced by chords in fourths.

The hymn-like melody of the substantial slow introduction undergoes unexpected harmonic shifts, and to Ives, “it suggested something that nature and human nature would sing out to each other—sometimes.” The central Largo cantabile, according to Ives, “tries to relive the sadness of the old Civil War days,” with the violin soaring over the dark chords in the piano. In the concluding Allegro, Ives heard “the hymns and actions of the farmers’ camp meeting, inciting them to work for the night is coming.”

Charles Ives: Violin Sonata No. 2 (Adam Bruderek, violin; Anna Prabucka-Firlej, piano)

Wrong Ears

Charles Ives © The Classical Review

In a funny anecdote, Ives relates that he invited the German violinist Franz Milcke to play over the First and Second Sonatas. “The ‘Professor’ . . . started to play the first movement of the First Sonata. He didn’t even get through the first page. He was all bothered with the rhythms and the notes and got mad. He said, “This cannot be played. It is awful. It is not music, it makes no sense.”

He couldn’t get it even after I’d played it over for him several times . . . and said, “When you get awfully indigestible food in your stomach that distresses you, you can get rid of it, but I cannot get those horrible sounds out of my ears.” . . . After he went, I had a kind of feeling which I’ve had off and on. . . . Are my ears wrong? No one else seems to hear it the same way.”

Violin Sonata No. 2

Charles Ives’ Violin Sonata No. 2

Ives left no specific comments on his Second Sonata, merely suggesting that the second movement “was based on the old ragtime stuff written about the time that I wrote so many of these ragtime dances.” Once again, Ives combines neo-romantic influences with inspirations of American dance and functional music with American hymns. And each movement is identified with a descriptive title.

The first movement, Autumn, does not refer to that particular season but to the hymn-tune “AUTUMN,” usually sung to the text “Mighty God! While angles bless Thee.” In the event, the movement is a dialogue between two rather contrasting themes. The second movement, “In the Barn,” is full of old fiddle tunes, and the concluding “The Revival” evokes a raucous camp meeting based on the early American hymn tune “NETTLETON.”

Charles Ives: Violin Sonata No. 3 (Hansheinz Schneeberger, violin; Daniel Cholette, piano)

Violin Sonata No. 3

Charles Ives’ Violin Sonata No. 3

Finished in late 1914, the Third Sonata relies on previously composed material. The first and third movements originated with organ preludes from 1901, and the central movement emerged from a ragtime movement from 1905. According to Ives, this Sonata “is an attempt to express the feeling and fervor—a fervor that was often more vociferous than religious—with which the hymns and revival tunes were sung at Camp Meetings held extensively in New England in the 70’s and 80’s. The tunes used or suggested are: “Beulah Land,” “There’ll Be No More Sorrow,” and “Every Hour I need Thee.” Common themes are used with or against the hymn tunes.”

The large and slow first movement is a magnified hymn in four “verses,” each followed by the same refrain. The quick second movement begins with the piano alone in dance-type music, suggesting “a meeting where the feet and the body, as well as the voice, add to the excitement.” Ives writes, “the last movement is an experiment: the free fantasia is first; the working-out develops into the themes, rather than from them; the coda consists of the themes for the first time in their entirety and in conjunction…. The tonality throughout is supposed to take care of itself.”

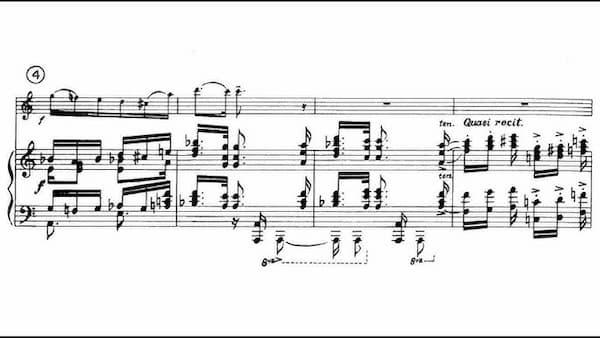

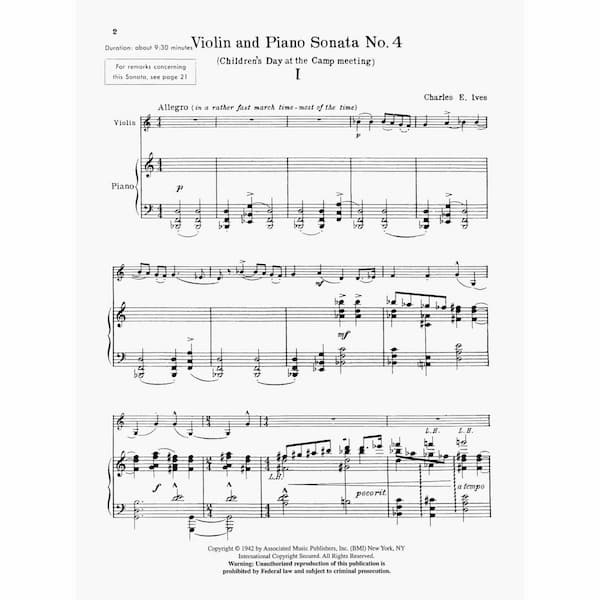

Violin Sonata No. 4

Charles Ives’ Violin Sonata No. 4

In 1916, Ives composed his Fourth Sonata, subtitled “Children’s Day at the Camp Meeting,” specifically for his twelve-year old nephew Moss White Ives. As a result, it is technically less intricate, smaller in scope and lighter in mood. However, its narrative closely connects to the Third Symphony and the Third Violin Sonata. As Ives wrote in the note included in the score, “The subject matter is a kind of reflection, remembrance, expression, etc. of the children’s services at the outdoor summer Camp Meetings held around Danbury and in many of the farms in Connecticut….”

The first movement was suggested by an actual event. As Ives reports, “the organist’s postlude practice and the boys’ fast march go to joining in each other’s sounds, the loudest singers singing wrong notes.” The second movement combines the hymn “Yes, Jesus Loves Me” with the sounds of nature on a summer day. And in the concluding movement, the boys are marching again, with memories fading, hesitating, and finally stopping altogether.

The notion of Ives as an isolated, idiosyncratic, and uniquely American figure has recently been challenged by a number of studies placing Ives squarely within his times. He had strong links to European composers ranging from Bach to Scriabin, “drawing on traditional practices while also developing new innovations.” And he also backdated his scores to sound more modern than he really was. As scholars put it, “the picture that is emerging is increasingly well-rounded, embracing the contrasts and contradictions that both Ives and his music so richly embodied.” Happy Birthday!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Charles Ives: Violin Sonata No. 4 “Children’s Day at the Camp Meeting” (Pekka Kuusisto, violin; Joonas Ahonen, piano)