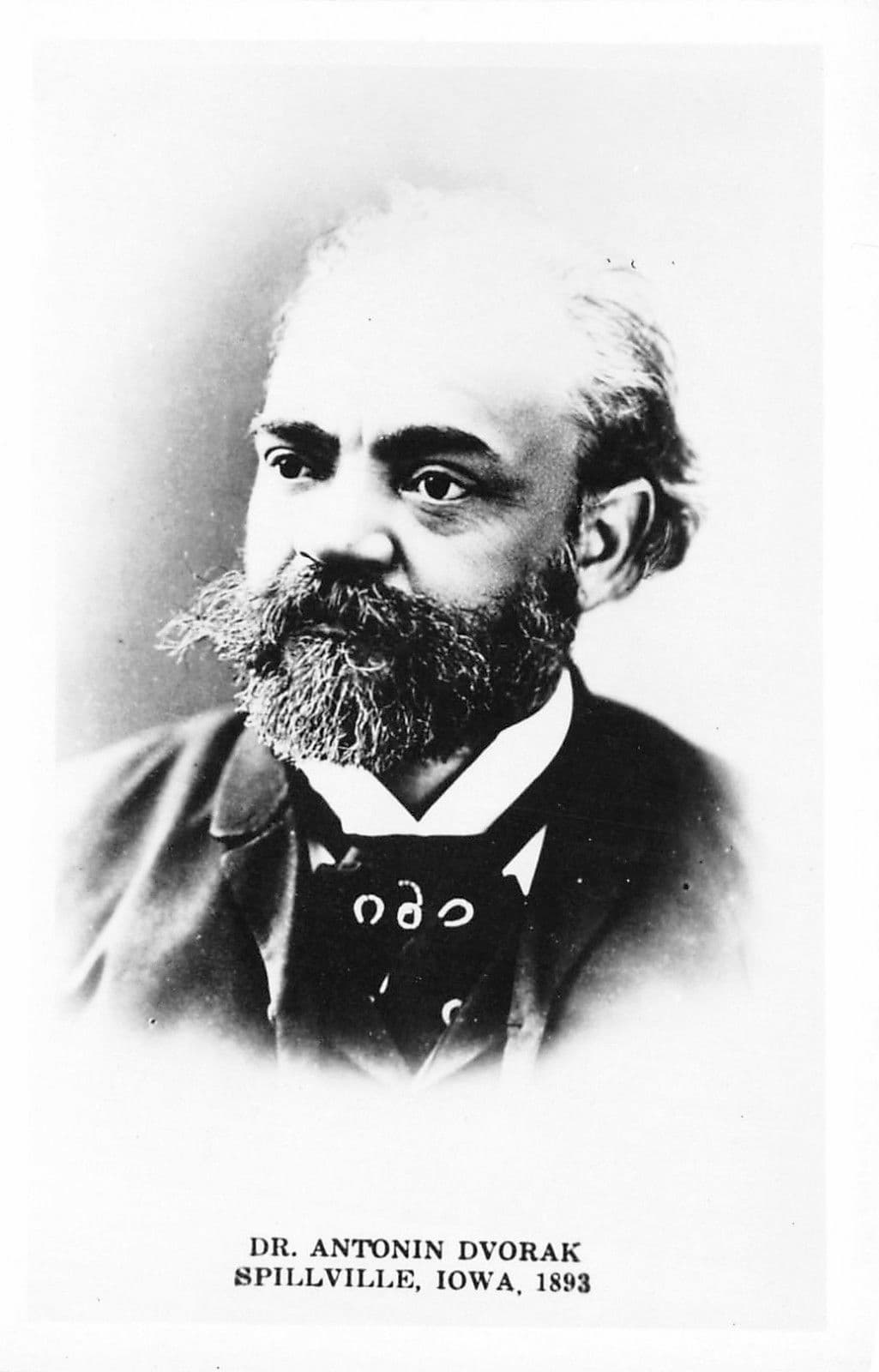

The traditional image of Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) as a simple Czech fellow with a flair for composing symphonic and chamber music has recently given way to “one of a complex figure writing works filled with hidden drama and secret programs.” In fact, the leading Dvořák scholar Michael Beckerman has argued that the “composer suffered from a debilitating and previously unexplored anxiety disorder.”

Antonín Dvořák

It just goes to show that despite an enormous amount of previous attention from scholars and critics, the composer has remained an elusive figure. We do know that he carefully cultivated a Czech personal and musical identity throughout his life. Yet, he was at home in a variety of different environments. Dvořák spoke Czech, German, and English and seems to have self-consciously cultivated an “American” compositional style later in life. Beckerman’s study will surely shed new light on Dvořák’s compositions, and further illuminated his artistic and intellectual friendships.

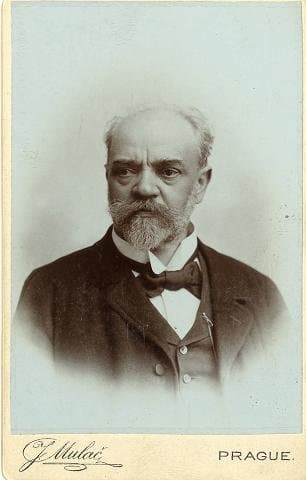

Hans von Bülow

Dvořák stuck up one such friendship with the conductor Hans von Bülow (1830-1894). Bülow played an important role in promoting Dvořák’s music in German-speaking countries, and he first conducted the “Hussite Overture” on 1 November 1886 in Hamburg. From then on, Bülow performed this work in practically all his concerts. When Bülow led Dvořák’s 7th Symphony to an enthusiastic reception in Berlin, the composer attached a photo of the conductor to the score and added the words, “Hurrah! You brought this work to life!”

Antonín Dvořák: Hussite Overture, Op. 67 (Berlin Staatskapelle; Otmar Suitner, cond.)

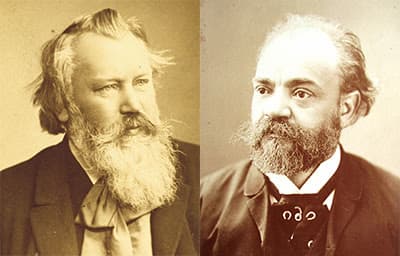

Johannes Brahms and Antonín Dvořák

Antonin Dvořák was profoundly nationalist in many respects. Nevertheless, among the great composers of the 19th century, his cosmopolitan musical tendencies were probably only equaled by Liszt and Tchaikovsky. A good many features of his musical language that are supposed to show clear signs of “nationalism” are unequivocally musical gestures of internationalism. Although elements of Slavonic folklore, inspired by his study of folk collections, began to permeate his musical language at an early stage, he took Johannes Brahms as his musical model.

Brahms and Dvořák were good friends from the start, a relationship fuelled by mutual admiration and interest in each other’s new compositions. The friendship certainly existed apart from the established prejudices of German criticism regarding the music of Dvořák. Despite their different nationalities, the lives of the two composers exhibit a number of striking parallels: Origin in the lower middle class, a rise in social status, and receipt of official honors; Middle-class existence maintained primarily by composing; Secured positions, concertizing, and teaching activities remained relatively marginal; Early musical education conservative and provincial; Achievements of world acclaim within a lifetime, but both were humble characters not suited to the role of the superstar. No wonder they got along famously.

Antonín Dvořák: Slavonic Dances, Series 1, Op. 46 (Cleveland Orchestra; George Szell, cond.)

Karel Bendl

Antonín Dvořák met the composer, conductor, and choirmaster Karel Bendl (1838-1897) during his studies at the organ school in Prague. An enduring friendship developed, and during the early 1860s young Dvořák was a frequent guest at the home of the wealthy Bendl family. He was given free access to the piano and a considerable archive of sheet music. Dvořák dedicated his first song cycle Cypresses to “my good friend Karel Bendl, as a token of our friendship.” Bendl wasn’t particularly excited, and he told Dvořák “that the declamation was in many places poor; a year later, when I by chance got my hand on this miscarried product, I realized to my delight that Mr. Bendl’s statement had been quite to the point.”

Josefína Čermáková

This collection of “lyrical and epic poems” emerges from Dvořák’s attempt to find his way as a composer. However, when giving piano lessons to supplement his income, he fell in love with his student Josefína Čermáková, the elder sister of his later wife Anna. Josefina wasn’t much interested, and Dvořák wrote to his publisher Simrock “Just imagine a young boy who is in love—that is the content of Cypresses.”

Antonín Dvořák: Cypresses, B. 11 (Marcus Ullmann, tenor; Martin Bruns, baritone; Andreas Frese, piano)

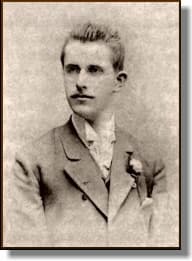

Josef Jan Kovarik

Josef Jan Kovarik (1870-1951) first met Dvořák during his violin studies at the Prague Conservatoire. In fact, they met in a Prague bookstore when Kovarik was buying English language newspapers. Kovarik was born in Spillville, Iowa, son of Czech immigrants to the United States. Kovarik, on the recommendations of Dvořák, would subsequently be appointed director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York City. But more importantly, he accompanied Dvořák and his family on their journey to America. Kovarik became a faithful guide, assistant, and friend, and he virtually became a member of the Dvořák family. He invited the composer to spend the summer holidays in his hometown of Spillville, and watched him compose the “New World Symphony,” whose first copy he made. In a remarkably short time, Dvořák composed his F major Quartet, Op. 96, and played through the work with his friend. Kovarik regarded the two-and-a-half years spent with Dvorak as the happiest years of his life and he recorded many valuable memories of this period in his copious correspondence with the Dvořák biographer Otakar Sourek. And he tirelessly promoted Dvořák’s compositions in America.

Antonín Dvořák: String Quartet No. 12 in F major, Op. 96 “American” (Pannon Quartet)

Emma Albani

Emma Albani (1847-1930) was a celebrated Canadian soprano who performed to critical acclaim in some of the most illustrious opera houses around the world. She performed in several Dvořák oratorios at music festivals in England and wrote the following about the composer. “He was an immensely fascinating and distinguished man, but also an extremely humble musician… I studied The Spectre’s Bride for four weeks. During rehearsals I was unpleasantly surprised that my interpretation of some of the solos differed from Dvořák’s conception, but we ultimately found a compromise and I sang it the way he wished without having to suppress my original ideas too much.” We do know that Dvořák regarded her as a fine singer. As he wrote to a friend, “I was told that, after Albani had sung ‘I beg thee, on thy dusty feet my lips I would lay,’ the audience was so moved that people were weeping and wiping the tears from their eyes. Albani’s performance was captivating indeed!! But I don’t need to tell you that.” In her memoirs Albani claimed to have been the inspiration for Dvořák’s “Stabat mater,” and that the soprano part had been written expressly for her.

Antonin Dvořák: The Spectre’s Bride, Op. 69 (English) (Oksana Krovytska, soprano; John Aler, tenor; Ivan Kusnjer, bass-baritone; Westminster Symphonic Choir; New Jersey Symphony Orchestra; Zdeněk Mácal, cond.)

Hanus Wihan, Antonín Dvořák and Ferdinand Lachner

Shortly before setting out for America, Antonín Dvorák put on a farewell concert tour with his friends Ferdinand Lachner (violin) and Hanus Wihan (cello). The tour lasted from 3 January to 29 May 1892 and was devoted to his compositions, including several arrangements of his early pieces for cello and piano. In all, the trio performed 40 concerts, all anchored by the great “Dumky Trio.” The premiere of that spectacular trio in February 1891 in conjunction with Dvorák being awarded an honorary doctorate by the Charles University of Prague had already featured Ferdinand Lachner (1856-1910). Lachner was born in Prague, and he attended the Prague Conservatory. He subsequently held concertmaster positions at Breslau and Warsaw, before returning to Prague to take on an appointment at the Conservatory. Dvorák and Lachner developed a deep professional friendship, and both had already embarked on a journey through the Bohemian Forest during the summer of 1878.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio No. 4 in E minor, Op. 90 “Dumky” (Joachim Trio)