Most people who read Dante’s La Divina Commedia love the first part of the trilogy, like the second, and often abandon the whole enterprise when they get to Paradise. The evil is just more interesting, somehow. Dante’s object lessons in how people went wrong and the price they must pay causes the reader to pause and reflect on how they might see those models in their own lives.

Dante

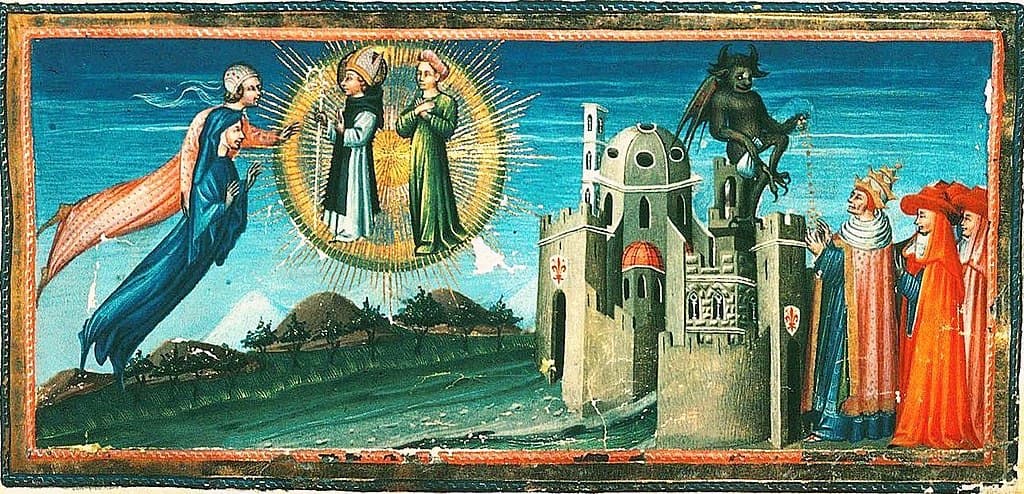

Domenico di Michelino’s 1465 fresco in the Florence Cathedral shows hell on the left, purgatory, and the city of Florence in the centre and, on the right, and above him, the spheres of Heaven, and, in the foreground, Dante holding a copy of The Divine Comedy.

Domenico di Michelino: Dante, 1465 (Florence Cathedral)

Dante’s extensive narrative poem, which he began around 1308 and completed around 1321, shortly before his death, divides the afterworld into 3 places and his poem into 3 parts: Inferno, for the lost and unrepentant; Purgatorio, for those working on redemption; and Paradiso, for the good.

Dante’s guide through Inferno and part of Purgatorio is the classical poet Virgil and he takes him through the 9 circles of hell, each level containing people of greater wickedness until he reaches the bottom, where Satan is held in bondage.

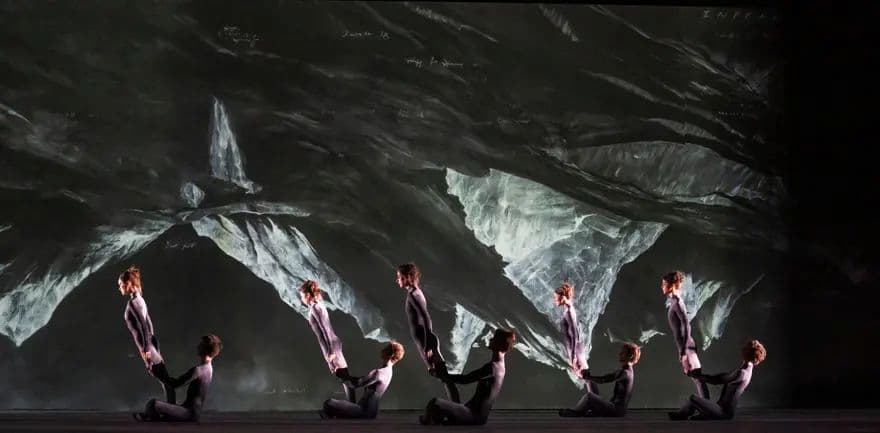

Royal Ballet: The Dante Project: Purgatorio

The English composer Thomas Adès (b. 1971) used The Divine Comedy as the source for his 2022 ballet Dante (called The Dante Project by The Royal Ballet). He opens by depicting Dante’s headlong flight through the ill-lit wood towards the opening of the track down to Hell.

Thomas Adès: Dante – Part I, “Inferno”: Abandon Hope – (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

After passing through Limbo (the first circle), the place for those worthies who lived before Christ and therefore cannot ascend to Paradise, Dante and Virgil encounter Paolo and Francesca in the Second Circle (Lust). Here, the condemned allowed ‘their appetites to sway their reason’. Francesca da Rimini was married to the deformed Giovanni Malatesta for political reasons but fell in love with his younger brother Paolo. When Giovanni discovered them together, he killed them both. Now they reside in Hell, caught in an infernal whirlwind.

Royal Ballet: The Dante Project: Inferno

Thomas Adès: Dante: Part I, “Inferno”: Paolo and Francesca – the endless whirlwind (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

They progress through the Third Circle (Gluttony), the Fourth Circle (Greed), Fifth (Wrath), Sixth (Heresy), Seventh (Violence), Eighth (Fraud) and Ninth Circle (Treachery). The Eighth Circle is where we encounter a familiar figure from opera, Gianni Schicchi, who impersonated the dead Buoso Donati to claim his inheritance.

Thomas Adès: Dante: Part I, “Inferno”: The Thieves – devoured by reptiles (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

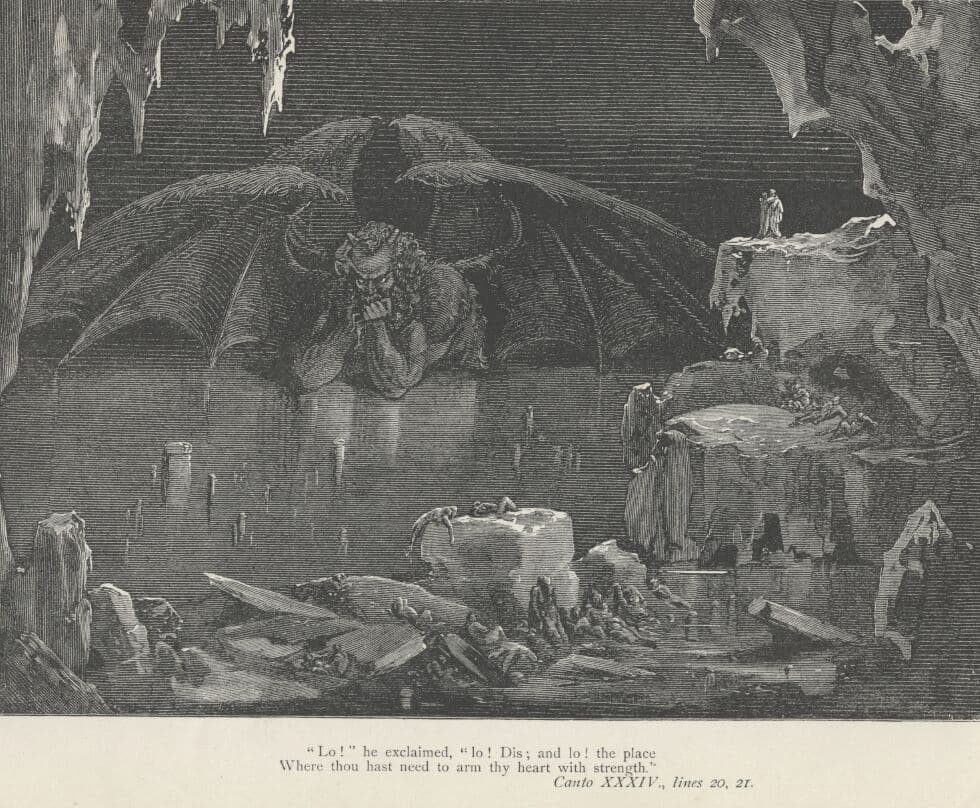

In Adès ballet, The Thieves is one of the favourite tracks (and has been released as a single), but we should remember that this is not the end of Inferno, we still have Satan to contend with. Lucifer, the arch-traitor, who rebelled against God and was cast down from Heaven to Hell, is held here in ice.

Gustave Doré: Canto XXXIV of Divine Comedy, Inferno, by Dante Alighieri

Thomas Adès: Dante: Part I, “Inferno”: Satan – in the lake of ice (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

Emerging from Hell, we’re in a new world and a new soundscape. Adès uses a recording of the pre-dawn prayer from the Sephardic Jews to open our new day.

Thomas Adès: Dante: Part II, “Purgatorio”: Dawn on the Sea of Purgatory – (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

As we descended into Hell, we now rise through the nine circles of Purgatory, depicted in Dante’s poem as an island-mountain in the Southern Hemisphere, rising from those in ‘Ante-Purgatory’, for the ‘souls whose penitent Christian life was delayed or deficient’ through circles that represent the seven deadly sins: Pride, Envy, Wrath, Sloth, Avarice, Gluttony and Lust. Although these may seem to be the same kind of sins that got so many sent to Hell, here, they are sins of motives, rather than of actions. They are all, really about love: love that creates harm (pride, envy, wrath), love that is deficient (sloth), and the last 3 are excess love (avarice, gluttony, and lust).

In Dante’s poem, we encounter many former leaders: Pope Adrian V (desire for power), Charles II of Naples (selling his daughter to a disreputable man), Philip IV of France who arrested Pope Boniface VIII in 1303, Midas (lust for gold), and so on.

At the top of Purgatory, Dante leaves Virgil and takes on a new guide: Beatrice, his ideal love, admired from afar during life.

Thomas Adès: Dante: Part II, “Purgatorio”: The Ascent (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

The Royal Ballet: The Dante Project: Paradiso (Edward Watson (Dante) with Sarah Lamb (the heavenly Beatrice)

Beatrice, who commissioned Virgil to help Dante on his journey and who symbolises the path to God, was the subject of Dante’s unrequited love on earth. Dante must leave Virgil, who represents human reason, and follow Beatrice who represents divine grace. As he leaves Purgatorio, having been washed in the River Lethe, which erases the memory of past sin, and drinks from the River Eunoë, which restores good memories, he is ‘pure and prepared to climb unto the stars’.

Philipp Veit: Dante and Beatrice speak to the teachers of wisdom Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, Peter Lombard and Sigier of Brabant, 1817–1827 (Rome: Casino Massimo)

Ascending from the top of Mount Purgatory (the Earthly Paradise), Dante again is faced with 9 circles, based on the observable heavens: Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Fixed Stars, and the Primum Mobile.

The First Circle, the Moon, represents the Inconstant, where he meets women who were forcibly removed from their convents, usually for marriage. Beatrice believes these women should have fled back to their holy shelters where they gave their vows.

Mercury, the Second Sphere, contains the Ambitious, or those who did good out of a desire for fame but who were deficient in the virtue of justice.

Venus, the Third Sphere, as for The Lovers, who were deficient in the virtue of temperance. The troubadour Folquet de Marseilles appears here, condemning the city of Florence for corrupting the church.

Giovanni di Paolo: Folquet de Marseilles bemoans the corruption of the Church, with the clergy receiving money from Satan at the right, 1441 (British Library, Yates Thompson MS 36, fol. 145r)

At the Fourth Sphere, the Sun, Dante meets the Wise, who illuminates the world intellectually. Mars is the Fifth Sphere, for the Warriors of the Faith, and Jupiter is the Sixth Sphere, for the Just Rulers. The Contemplatives are at Saturn, the Seventh Sphere, where Dante and Beatrice meet Saint Benedict, head of the Benedictine order, who laments how worldly his monks have become.

The Eighth Sphere is the Fixed Stars, representing Faith, Hope, and Love, or the Church Triumphant. St Peter questions Dante on Faith, St James questions him on Hope, and St John questions him on Love. Dante, with the help of Beatrice, answers the questions successfully and passed to the final Sphere, The Primum Mobile (the ‘first moved’ sphere), represented by The Angels. The Ninth Sphere is moved directly by God and causes all the other spheres to move.

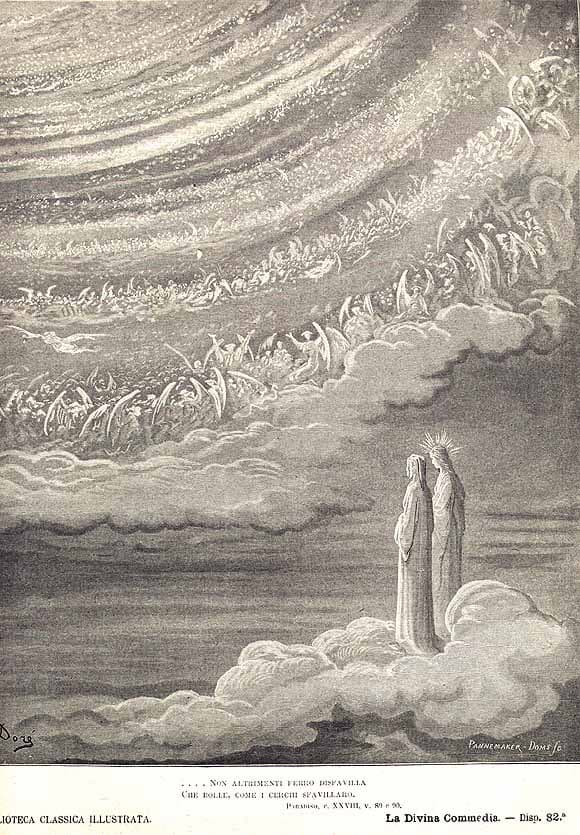

Gustave Doré: Dante and Beatrice see God, 1867

Dante and Beatrice see God as an intense point of light, surrounded by 9 rings of angels. They ascend to The Empyrean, where Beatrice is replaced by St. Bernard, a mystic, as his guide. Dante comes face to face with God and in a final flash of understanding, his soul becomes aligned with God’s love.

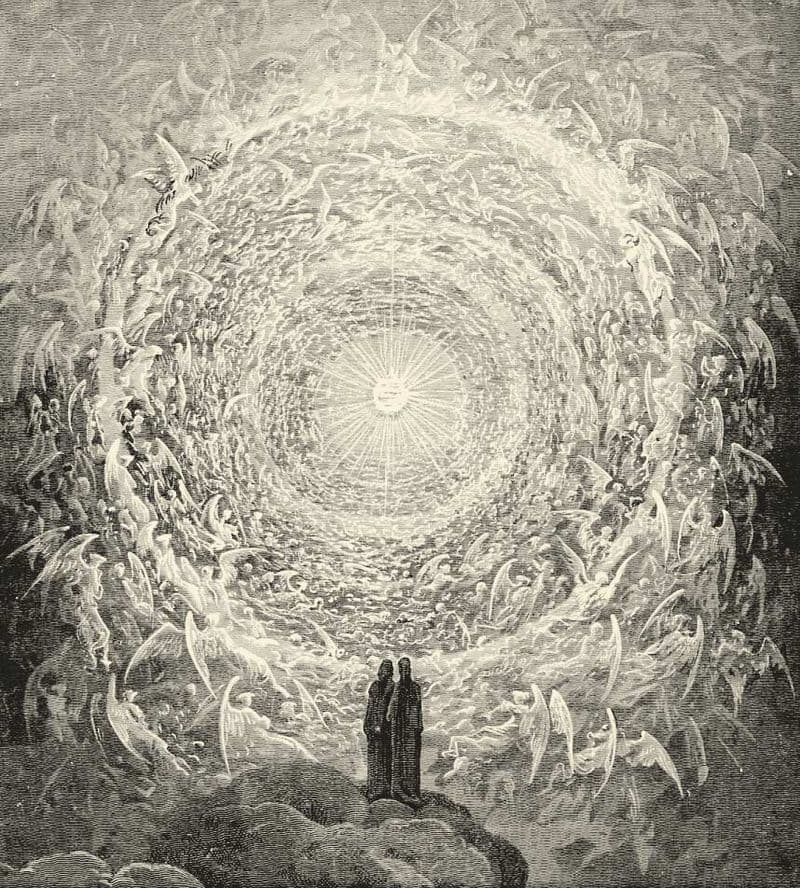

Gustave Doré: The Empyrean, 1867

In Adès’ ballet, the totality of Paradiso is a single movement. Just as we did with Purgatorio, we enter a new musical world. As much as for Dante, Paradiso cannot be described in words, for Adès, he brings out many of the ideas that have been important in his earlier works: ‘his “obsession” with spirals, the chronic instability of musical notes, and the “magnetic forces within the notes”’. The movement is restless until the final revelatory perfection of arrival. The key of arrival is the key of C, or, as Adès puts it, ‘the human key…the peoples’ key’.

Thomas Adès: Dante: Part III, “Paradiso”: Awakening – Moon – Mercury – Venus – Sun – Mars – Jupiter (The Eagle) – Saturn (The Golden Ladder) – Fixed Stars – Empyrean (Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; Gustavo Dudamel, cond.)

No other composer has taken on the entirety of The Divine Comedy. Liszt based his Dante Symphony on Inferno and Purgatorio, Puccini created his opera around the character of Gianni Schicchi, and Tchaikovsky took on the story of Francesca da Rimini in his opera of the same name. Adès has created not only a full-length ballet but also an epic orchestral work in this dual commission from the Los Angeles Philharmonic and The Royal Ballet.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter