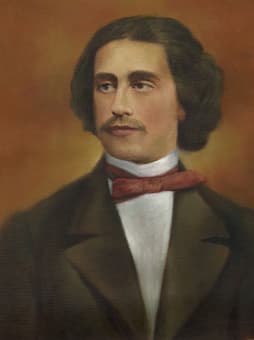

Josef Strauss © Naxos Digital Services

The musical Strauss family dynasty took full advantage of the pleasure-seeking and carefree spirit of Imperial Vienna. As members of the public piled into the great dancehalls of the city, the Strauss family gleefully provided the musical background that gaily sent the Viennese population into throbbing gyrations. As leaders of the string section in the Strauss Orchestra, they fiddled their way into the hearts and beds of numerous young maidens. Johann Strauss I and Johann Strauss II—widely known as the Waltz King—became the darlings of the Viennese dance craze and the objects of female desire. Messy divorces, squabbles over illegitimate children and an occasional suicide attempt were all part of the Strauss musical empire. Josef Strauss (1827-1870), son of Johann I and brother of Johann II, however, wanted nothing to do with all that debauchery. He was a quiet and shy individual, who initially became an industrious engineer for the city of Vienna. He did take over shared responsibility for the Strauss Orchestra when Johann II became seriously ill. However, all he ever wanted in his private life was to marry his childhood sweetheart, the seamstress Karoline Pruckmayer (1831-1900). And that’s exactly what happened on 8 June 1857 in the St. Johann Parish Church in Leopoldstadt.

Josef Strauss: Perlen der Liebe, Op. 39 (Pearls of Love) (Vienna Johann Strauss Orchestra; Jack Rothstein, cond.)

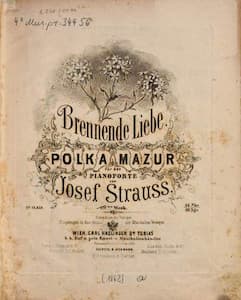

Josef Strauss’ Brennende Liebe, Op. 129

As a wedding present to his wife, Josef Strauss composed his concert waltz “Pearls of Love.” That remarkable piece of music is not merely a sparkling ballroom trinket, but Josef expanded on the traditional form of Viennese dance music. As he subsequently wrote to his wife, “As I do not want to practice the trade of beer-fiddler forever, I am turning to other kinds of composition.” Of great importance is an unmistakable symphonic development, which relies on stylistic influences from Richard Wager and Franz Liszt. Josef Strauss called it a “concert waltz,” nudging the genre away from the ballroom and into the concert hall. The first review already noted the special character of the composition, suggesting, “the newly-composed waltz is offered in a wholly original structure in new form.” In fact, “the work is remarkable for its conception and power, surpassing anything that his famous brother Johann II had yet created.” Josef’s talents as a composer were immediately recognized, but even more importantly, his marriage to Karoline was happy, successful and fulfilled. Their daughter Karolina Anna was born on 27 March 1858.

Josef Strauss: Brennende Liebe, Op. 129 “Burning Love” (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Willi Boskovsky, cond.)

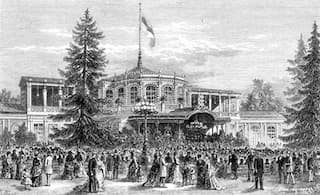

Pavlovsk Music Pavilion and Train station

In the summer of 1862, Josef’s mother Anna—keeping track of all business aspects of the Strauss Empire—ordered her son Josef to travel to Russia. Originally, Johann II was supposed to direct the concerts of the Strauss Orchestra in Pavlovsk near St. Petersburg. However, the Waltz King was under the weather, and as soon as Josef arrived, he returned to Vienna and got married. Josef wasn’t particularly happy to be drafted to Russia, but he willingly substituted for his brother. Once he had returned to Vienna, Josef immediately presented a new set of waltzes that included the polka mazurka “Burning Love.” Originally it was assumed Josef had named this work after a popular flower. In the event, this polka has nothing to do with flowers, but musically encodes Josef’s burning love for his wife, as it was composed in Russia during this unexpected period of separation.

Josef Strauss: Die Emancipirte, Op. 282 (The Emancipated Woman) (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Willi Boskovsky, cond.)

Graveyard of Josef Strauss

The first heated debates about the position of women in society and the idea of women’s liberation was a hotly debated issue in Vienna during the middle of the 19th century.

The debut of violinist Marie Grüner as conductor of Vienna’s well-known Ludwig Morelli Orchestra in 1860 was treated in numerous newspaper articles as an example of women’s emancipation, and the debates were revived as women attained high positions in business and the arts. The first female university students and the first women doctors certainly made headlines. Josef Strauss was extremely happily married to Karoline, and he wished for nothing else than to free his wife from the bonds of family and to be able to provide her with independent employment. In fact, he championed women’s causes in a whole sting of compositions, including “A Woman’s Heart,” “A Woman’s Dignity,” and the polka mazurka “The Emancipated Woman.” When the work premiered in 1870 at the ball of the Garden Society, Karoline was in the audience, and she knew that this work was especially addressed to her. In 1869, Johann II and Josef spent the summer season once more in Russia. Josef was feeling unwell, and he wrote to his wife, “I do not look good, my cheeks are hollower, I have lost my hair, I am becoming dull on the whole, I have no motivation to work.” Despite his physical ailments, Josef composed “From Afar” for Karoline. Shortly before the first performance, Josef wrote to his wife:

Always with you

only because of you and

forever for you!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

There is a letter somewhere part of which was once quoted in a Vienna New Year’s Day Concert, in which Josef wrote to his belovéd wife Karoline, that her anxiety that he would be rejected by the Russians on the grounds that he wasn’t his more famous brother Johann, was unfounded. He sent to her a copy of his newly-composed Polka “Ohne Sorgen,” signing his letter with the German words quoted in English at the head of this article: “Immer mit Dir, nur durch dich und ewig für dich,” signing it “Dein Peps.” We of course have always taken “Ohne Sorgen” to mean “Carefree,” but since knowing the contents of this letter, I have interpreted “Sei ohne Sorgen” to mean “Do not worry” since the rest of the sentence (in English) means: your anxiety that the Russians would reject me is without foundation. As far as I am aware no on (in Vienna) has ever found this letter in an archive; it isn’t even quoted in the late Prof. Mailer’s volumes. All I had to go on were the few lines as quoted by the Austrian Radio Announcer at the NYD Concert several years ago.