Claude Debussy is one of the most beloved composers in the classical music canon. Several qualities make his work especially unique:

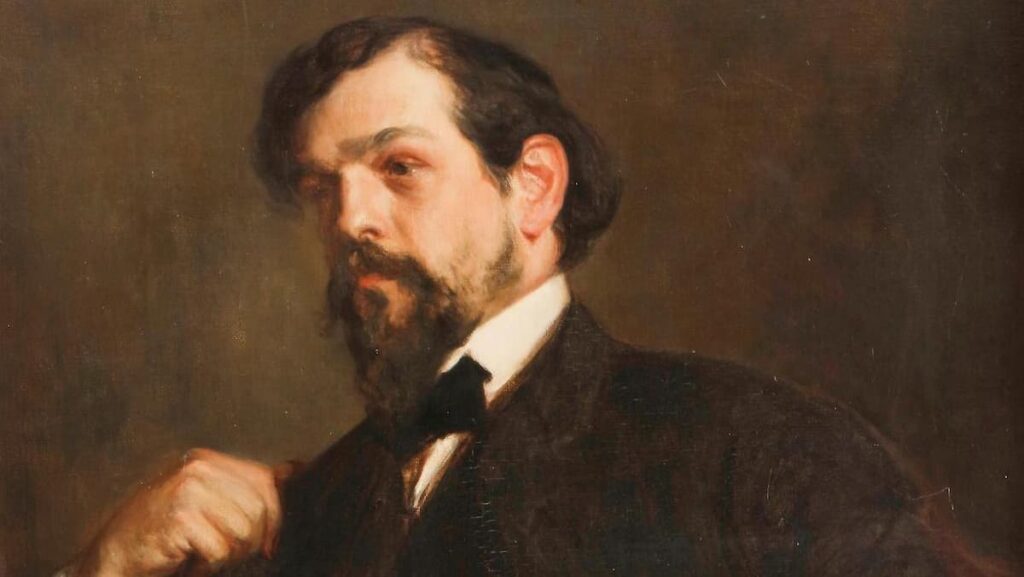

Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861-1942), Claude Debussy, 1902, oil on canvas, 95 x 74 cm/37.4 x 29.1 in.

- Use of colour and texture. Debussy was a master at using unusual combinations of instruments to create unique sounds.

- Harmonic innovation. Debussy loved using unusual and unexpected chords, as well as pentatonic scales not often used in Western music.

- Evocative titles and narratives. From “Clair de lune” (Moonlight) to La mer (The Sea) and beyond, Debussy was famous for painting musical pictures of real-life phenomena.

- Non-traditional forms. Debussy liked writing works free of expectations and preconceptions about form and structure.

Debussy: La mer | Bernard Haitink and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Of course, no other composer sounds exactly like Debussy, but many have employed at least some of these same elements in their own music.

Today, we’re looking at six composers who have a certain Debussy-esque je ne sais quoi.

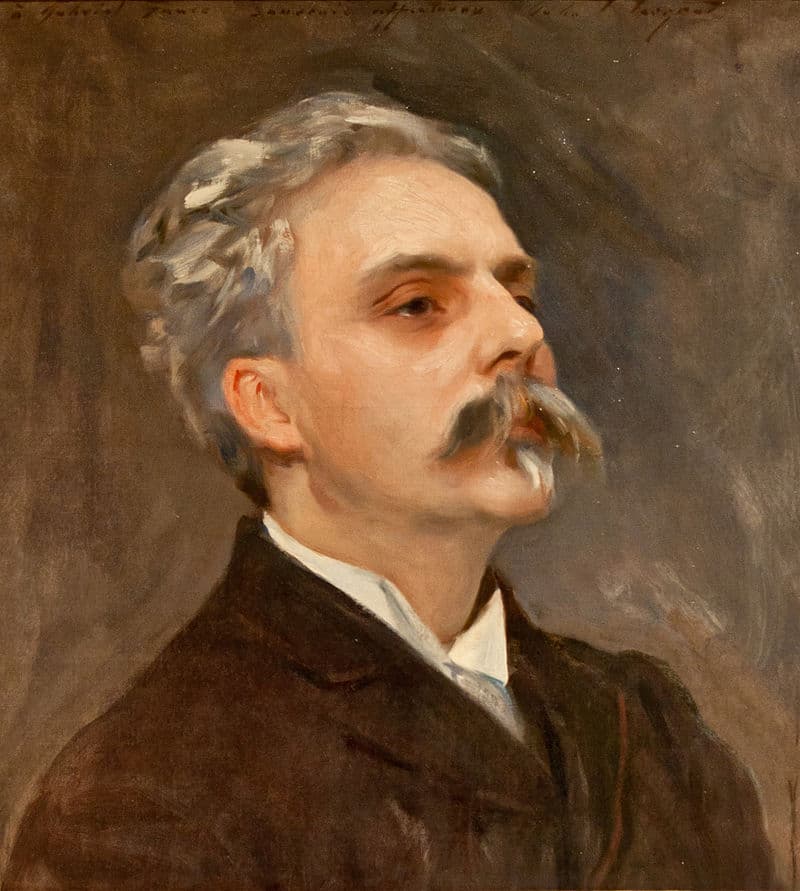

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924)

Gabriel Fauré: La chanson d’Ève, Op. 95

Like Debussy, Gabriel Fauré drew heavily on his French identity, helping to sustain and enrich a uniquely French tradition of music-making.

In life, however, the two composers were somewhat at odds.

Fauré said about Debussy’s 1898 opera Pelléas et Mélisande, “If that was music, I have never understood what music was.” Fauré wrote his own take on the Pelléas story that same year.

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1896

For his part, Debussy called Fauré a “master of charms” – in a way that wasn’t necessarily a compliment.

Learn more about their relationship here.

Interestingly, the men also both betrayed their respective wives to sleep with the same woman: the beautiful singer Emma Bardac, who had an affair with Fauré before falling in love and leaving her husband for Claude Debussy.

In their later years, both Debussy and Fauré gravitated toward simplicity in their writing. Fauré’s La chanson d’Ève song cycle, finished in 1910 when the composer was sixty-five, consists of a collection of texturally simple, poignant mélodies for voice and piano…and is a musical callback to his Pelléas et Mélisande suite.

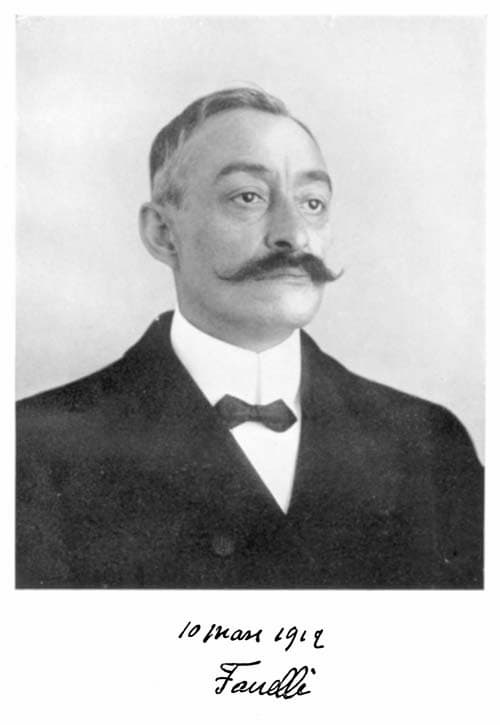

Ernest Fanelli (1860-1917)

Ernest Fanelli (1860-1917) : Thèbes, tableaux symphonique d’apres Le Roman de la Momie (1883)

Fanelli was born in 1860 in Paris, the son of two Italian immigrants.

He studied music with varying levels of seriousness throughout his childhood. At one point, he was expelled from the Conservatoire because he didn’t like a teacher. Eventually, he gave up due to lack of money.

In 1883, he wrote a daring symphonic poem called Thèbes. The manuscript lay in a desk until 1912, when, trying to get a copyist job, Fanelli sent it to composer Gabriel Pierné as an example of his handwriting. Pierné was astonished by it and arranged for a performance. Despite its age, it was rapturously received.

Ernest Fanelli

Thèbes employs a variety of elements that Debussy also enjoyed using, like an “exotic” setting, pentatonic scales, and strikingly unique harmonies.

Debussy said that Fanelli was “a composer with an acute sense of musical ornamentation, dragged towards such an extreme need of minute description, making him lose his sense of direction.”

Still, there’s something Debussy-ian at play in this tone poem written before Debussy’s most adventurous works.

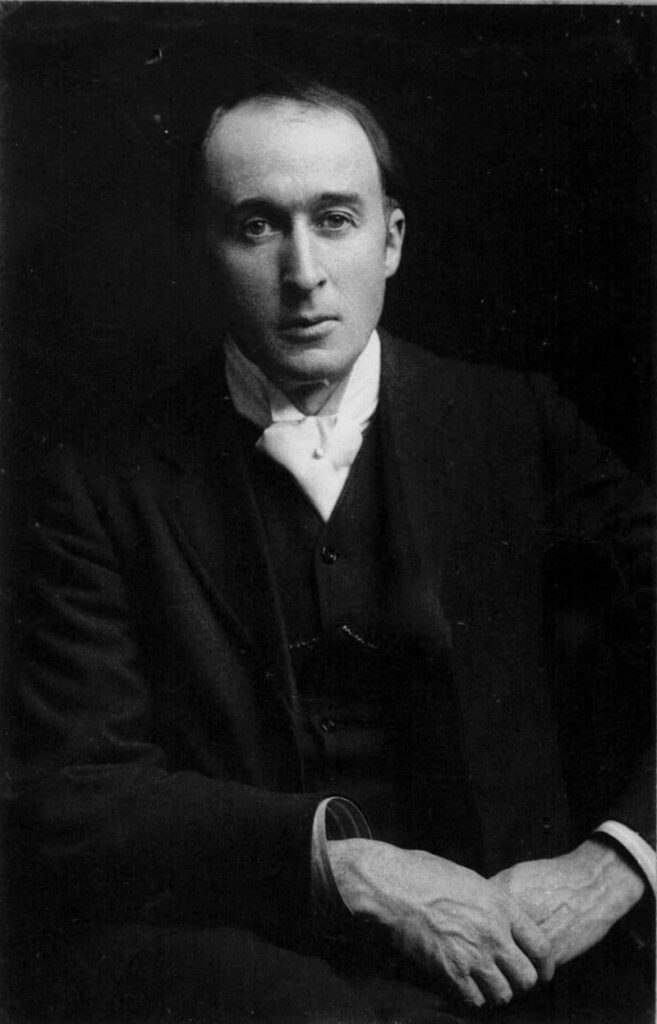

Frederick Delius (1862-1934)

Delius: North Country Sketches

Frederick Delius was born in 1862, the same year as Claude Debussy, in Yorkshire, England.

He was expected to join the family’s wool business, but he longed to become a musician instead. In the 1880s, his family sent him to run an orange plantation in Florida, but he used the time to learn about music instead.

In 1888, Delius moved to Paris. However, he spent more time with painters like Gauguin and Munch than the French composers. Perhaps because of his early lack of musical training, he never particularly identified with any one group of musicians.

Frederick Delius

In 1929, a critic at the Times wrote that Delius “belongs to no school, follows no tradition and is like no other composer in the form, content or style of his music.” Such independent iconoclasm is reminiscent of Debussy.

The two composers were also both interested in colourfully portraying natural phenomena in their music, which Debussy did so famously with La Mer.

Delius wrote North Country Sketches in 1913-14. These orchestral sketches portray autumn, winter, and spring in the woods and meadows.

Mary Howe (1882-1964)

Nocturne by Mary Howe

Mary Carlisle was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1882. She attended the Peabody Institute in Baltimore and later went to Paris to study composition under renowned composition teacher Nadia Boulanger.

Just like Debussy was interested in establishing a French musical identity, Mary Howe was interested in establishing an American one. She never relocated permanently to Europe and was an American composer through and through.

Mary Howe

This solo piano nocturne from 1925 is reminiscent of some of Debussy’s works for solo piano, especially his “Rêverie” from 1890.

Charles Tomlinson Griffes (1884-1920)

Recital at the Library of Congress- Solungga Liu plays The White Peacock by Charles Griffes

Charles Tomlinson Griffes was born in Elmira, New York. He studied music in both America and Berlin, then returned to New York and became a music director at a boarding school in Tarrytown, New York, about thirty miles away from New York City. He died tragically young of influenza.

This piece is from a four-movement suite Four Roman Sketches called “White Peacock”, and it was inspired by a bird that Griffes saw at a Berlin zoo: “Among the peacocks, was a pure white one – very curious.”

In his music, Griffes leans on many of the same traits that Debussy does, including surprising harmonies and unconventional, freeform, and freewheeling structures.

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

Lili Boulanger: D’un matin de printemps

Lili Boulanger was one of the great prodigies in music history. She started taking lessons at the Paris Conservatoire when she was only five, attending alongside her musical ten-year-old sister Nadia.

In 1917, she went on to become the first woman ever to win the prestigious Prix de Rome composition prize, which Debussy himself had won in 1884.

Based on her works, it is clear that she was fascinated by taking full advantage of the instruments’ unique colour and timbre.

Lili Boulanger

In her “D’un matin de printemps” (“Of a spring morning”) from 1918, one can hear clear echoes of Debussy’s La mer or L’isle joyeuse, but remade in a new style that is uniquely Boulanger’s own.

Although she was a full thirty-one years younger than Debussy, her health was poor, and she died ten days before him in March 1918 of Crohn’s disease.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter