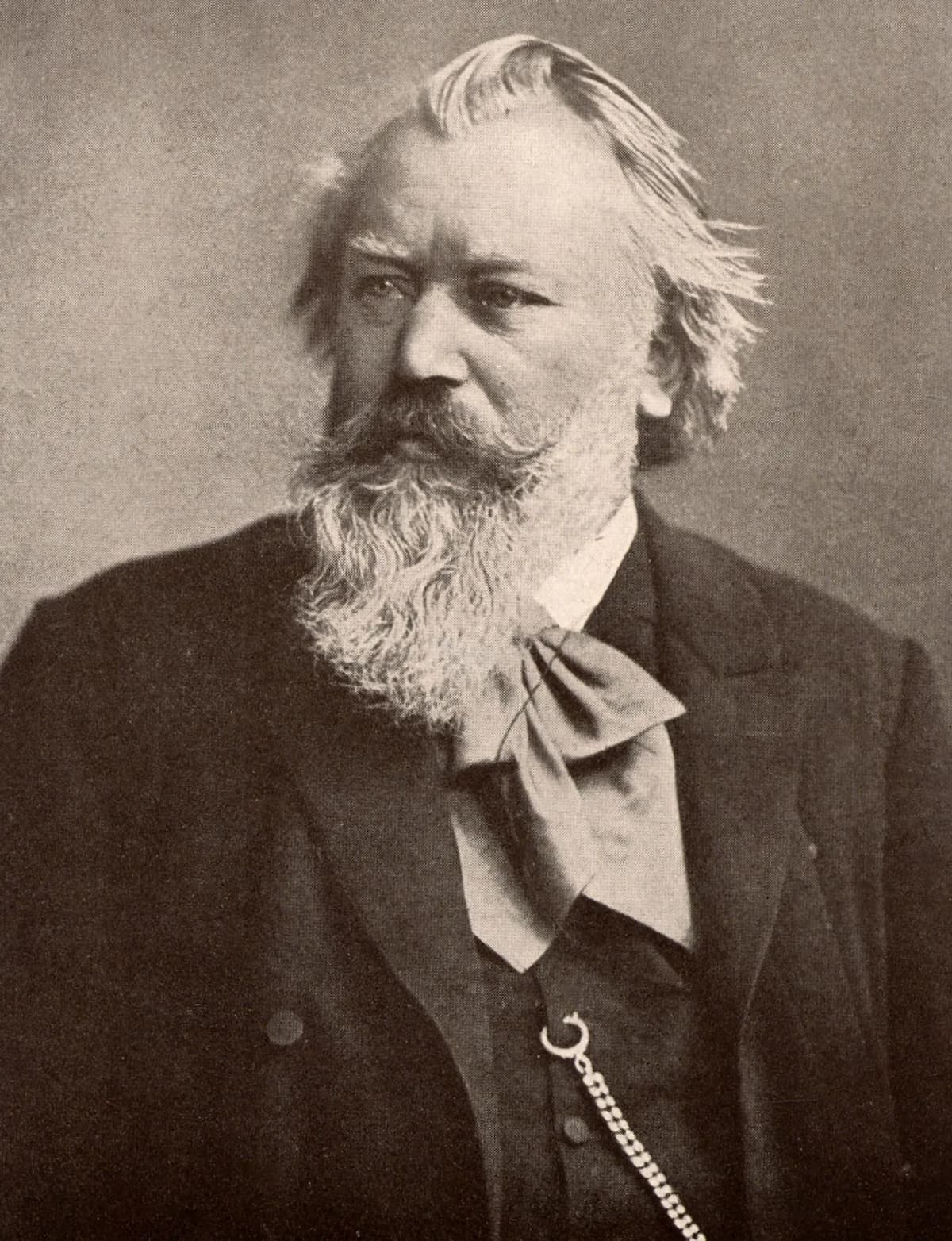

We’ve looked at compositions dedicated to Johannes Brahms before, let’s put our focus on various chamber music pieces dedicated to Brahms this time.

Brahms in Zürich

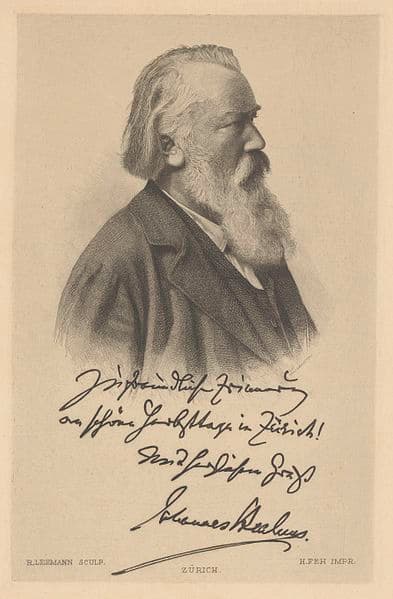

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95

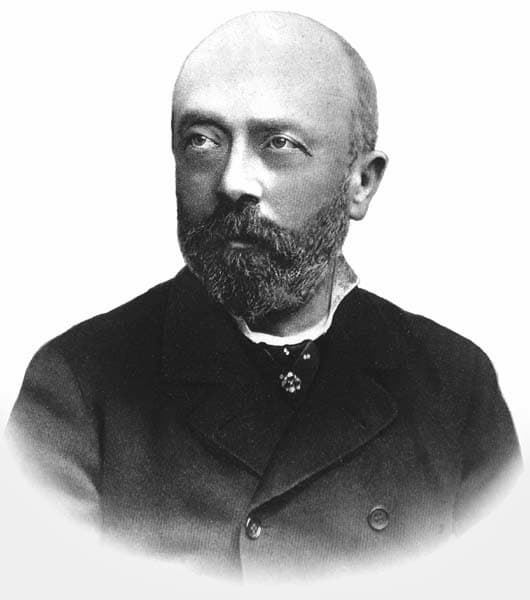

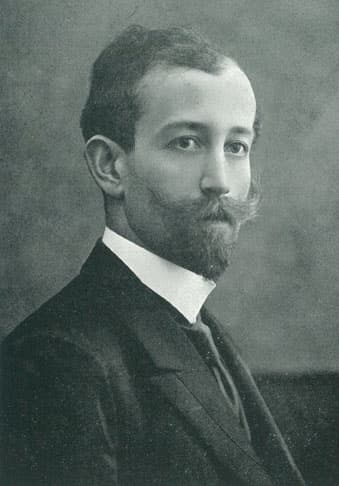

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95 (Andreas Frolich, piano; Belcanto Strings)

Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900) found in Brahms his ideal compositional model. As he writes, “He helped me, by the mere fact of his existence, to my development; my inward looking up to him, to his artistic and human energy, strengthened my weaker soul and drove it on restlessly to the point where I stand.” Brahms, however, never ventured to provide a positive assessment of Herzogenberg’s compositions, claiming, “He would be inclined to express such lavish praise that Herzogenberg might suspect his sincerity.” It is more likely, however, that while Brahms respected Herzogenberg’s technical craftsmanship and thorough musical knowledge, he “felt no enthusiasm for the compositions themselves.”

To his credit, Herzogenberg never stopped composing, as he wrote in a letter to Brahms in 1897. “There are two things that I cannot get used to doing: That I always compose, and that when I am composing, I ask myself, the same as thirty-four years ago, ‘What will He say about it?’ He is, of course, yourself. To be sure, for many years, you have not said anything about it, which is something that I can interpret as I wish. This has not, however, at all taken away from my admiration for you. And so I emphasise it again with a dedication for which I hope you will be so kind as to excuse me!” The referenced dedication belongs to the Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95, finished just days before Brahms’ death.

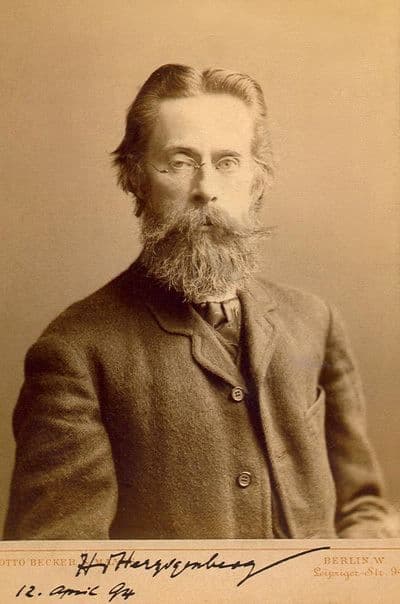

Hermann Goetz: Piano Quartet in E Major, Op. 6

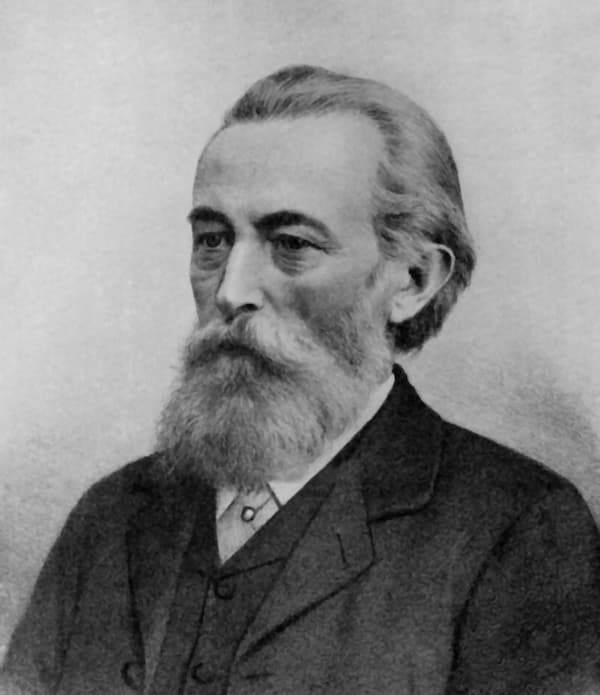

Hermann Goetz

Hermann Goetz: Piano Quartet in E Major, Op. 6 (Oliver Triendl, piano; Marina Chiche, violin; Peijun Xu, viola; Niklas Schmidt, cello; Matthias Beltinger, double bass)

Johannes Brahms first met Hermann Goetz in 1865 and again one year later when he attended the Zurich music festival. A funny anecdote tells that Goetz invited Brahms to lunch, but when he arrived with some friends, they were told by his wife that he was too ill to join his guests but wished them to stay and proposed to listen to their conversation from a darkened adjoining room. It has been suggested that given their very different characters and limited personal contact, “they were unlikely to have become intimate friends.” Brahms, however, seemed to have high regard for Goetz, as he called him “a splendid man” and a “most estimable musician.” In fact, Brahms recommended music by Goetz to his publisher Fritz Simrock, “not necessarily his piano concerto, but otherwise I, and you probably as well, know lovely works by him and the Taming of the Shrew has made his name known.” Goetz had also studied piano with Hans von Bülow, and for his final examination at the “Stern Conservatory” in April 1862, he played his first piano concerto, the work referenced by Brahms. His Piano Quartet in E Major, dating from the fall of 1867, is dedicated to Johannes Brahms. It is, according to some critics, “considered the masterpiece of the composer.”

Otto Dessoff: String Quartet in F Major, Op. 7

Otto Dessoff

Otto Dessoff: String Quartet in F Major, Op. 7 (Mandelring Quartet)

Otto Dessoff (1835-1892) occupied a special position in the performance history of works by Johannes Brahms. After all, Brahms entrusted him to conduct the first performance of his First Symphony in 1876. Brahms writes shortly after the premiere, “It has always been my secret, fond wish to hear the work for the first time in a small town which has a good friend, a good conductor, and a good orchestra.” They first met in Leipzig in 1853 and were in regular personal and professional contact after they both had settled in Vienna. Dessoff has been called “one of the outstanding conductors of this time, and the Viennese Philharmonic concerts owed their international reputation above all to Dessoff’s dynamic and purposeful direction.” Brahms seemed to have disagreed with that assessment and asserted that “Dessoff is most definitely and in no respect the right person to conduct the philharmonic concerts, as the standard of the orchestra had declined under him.” Brahms never shared his opinion with Dessoff, who dedicated his Opus 7 String Quartet to Brahms. Brahms encouraged him to publish it, and he also accepted the dedication “though in terms that fall markedly short of outright enthusiasm.” Brahms writes, “You give me the greatest pleasure by writing my name on the title page of the quartet—in that way we shall share the blows if people should consider it too puerile.”

Robert Fuchs: Piano Trio No. 1 in C Major, Op. 22

Robert Fuchs

Robert Fuchs: Piano Trio No. 1 in C Major, Op. 22 (Gould Piano Trio)

Johannes Brahms called Robert Fuchs (1847-1927) “a splendid musician; everything is so fine, so skillful, so charmingly invented that one cannot fail to be pleased.” Today, we primarily remember Fuchs as a teacher, as he was active as Professor of music theory at the Vienna Conservatory. One of his first students was Mahler, but also Wolf, Sibelius, Franz Schmidt, Schreker and Zemlinsky passed through his classes. Fuchs enjoyed a considerable reputation as a composer in his lifetime, and he made the acquaintance of Brahms in the late 1870s. Considering that Brahms never enjoyed proper schooling, he was always impressed by scholars and academics. Brahms warmly recommended the Fuchs cello sonata to Simrock, describing it as “his best and most spirited work today,” and he called Fuchs the “probably brightest talent in Vienna.” When Fuchs played his new piano duets to Brahms, he wrote to the publishing house C.F. Peters. “I have a special favourite among my colleagues whom I have long wished to see associated with you. He is Robert Fuchs, with some of his orchestral music and piano pieces you are no doubt familiar with. So there is no need for me to dwell at length on his genuine musical talent and on the beautiful and natural simplicity, gracefulness, and charm which characterize his compositions.” Already in 1879, Fuchs had dedicated his C Major Piano Trio to Brahms.

Eugen d’Albert: String Quartet No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 11

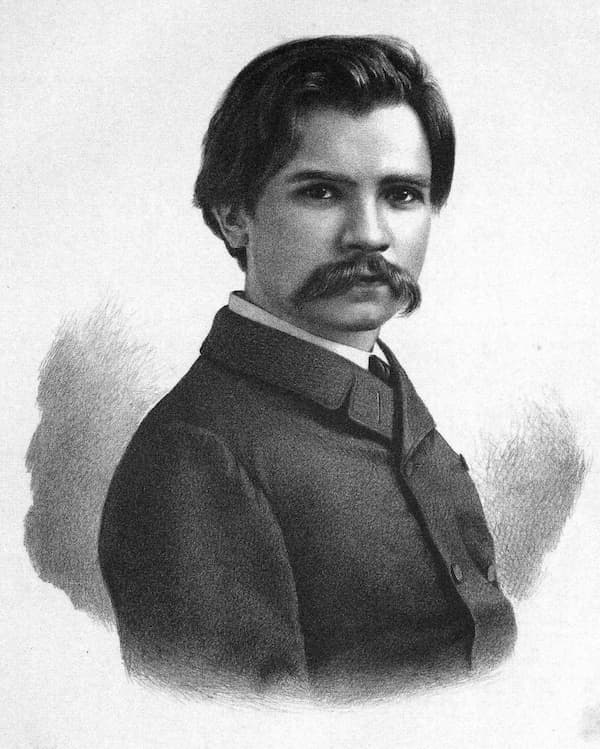

Eugen d’Albert

Eugen d’Albert: String Quartet No. 2 in E-flat Major, Op. 11 (Reinhold String Quartet)

Eugene d’Albert (1864-1932) was introduced to Brahms by Hans Richer on the occasion of an all-Brahms recital given by Bülow in Vienna in 1882. Brahms was very impressed by d’Albert’s playing and regarded him “as the ideal interpreter of his two piano concertos.” He was less enthusiastic about d’Albert’s compositions, and when he received the E-flat Major Quartet dedicated “in deepest veneration,” he responded thus. “Dear Friend, Your letter and package were the most amiable and dearest things that greeted me upon my recent return, and I thank you for the communication itself and quite especially, and with all my heart, for the dedication. For the time being, however, I am very satisfied and would very much like, not to write, but to chat about this and that at our leisure. There is but one thing I would most like to know. Hardly does your quartet get started, everyone will cry out: Aha, Beethoven’s final quartet in E-flat major! To my ears, however, the first movement reveals that you have a deep knowledge of the lovely lesser sonatas of Clementi and have attempted to imitate the admirable free yet masterly form of, say, his F-sharp minor or G-minor sonata. Does anyone nowadays appreciate these sorts of things? For today, these disorderly and hasty lines from your cordial and grateful Johannes Brahms.” D’Albert was rightfully deeply insulted, as Brahms curtly told him that he set out to compose like the great Beethoven but ultimately produced a minor work of Clementi. However, Brahms being Brahms, he insisted on a repeat performance in Leipzig shortly after the premier.

Carl Reinecke: Cello Sonata No. 3 in G Major, Op. 238

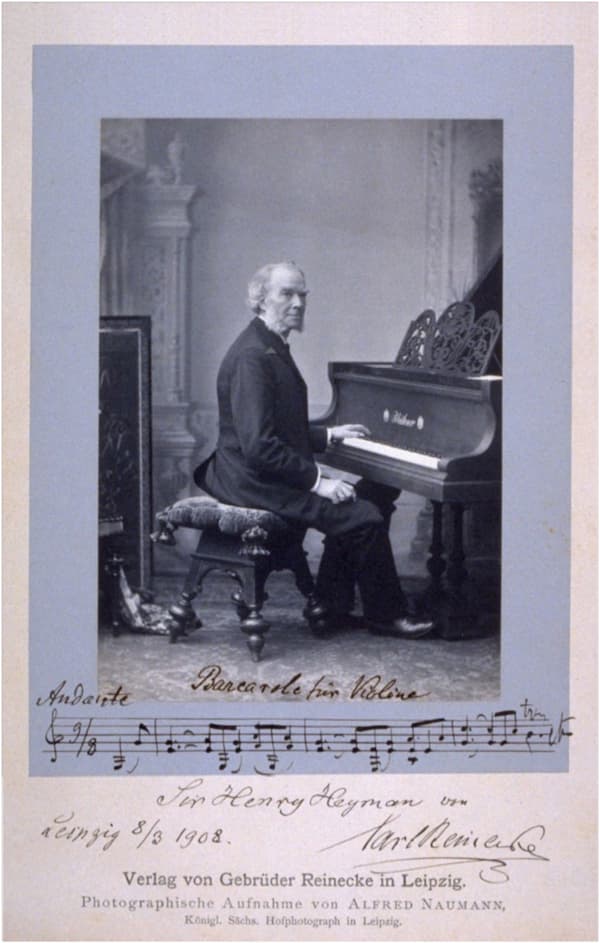

Carl Reinecke

Carl Reinecke: Cello Sonata No. 3 in G Major, Op. 238 (Ana Turkalj, cello; Aleck Carratta, piano)

In his youth, Carl Reinecke (1824-1910) greatly impressed both Mendelssohn and Schumann. Reinecke had made piano arrangements of Schumann songs, and he thanked him with the following words. “Basically, as you may well suspect, I am no friend of song transcriptions and have a genuine loathing for some of the Liszt ones. In your hands, dear Mr. Reinecke, I feel quite comfortable, and this comes from the fact that you understand me as few others.” Reinecke went on to publish 288 works with opus numbers and countless arrangements of works by other composers. Brahms was only 20 years old when he met Reinecke in Cologne in September 1853. Soon thereafter, Brahms mistakenly believed that Reinecke was involved with the publication of a highly negative critique of his published opp. 1-4 in 1854, which included a nasty personal attack. The assessment accused Brahms of “having made use of Schumann’s influential position in a shameful effort of self-promotion.” The Brahms biographer Max Kalbeck reported “that Brahms held a lifelong grudge against Reinecke.” The two men did finally spend some time together in Vienna in 1896, and Reinecke even published an account of their last meeting. In addition, he published his 3rd Cello Sonata in 1898 with the dedication “Den Manen Johannes Brahms” (To the spirit of Johannes Brahms).

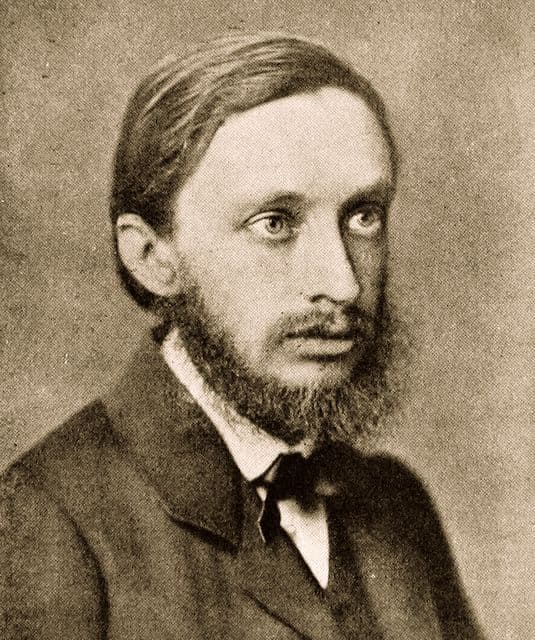

Adolf Jensen: Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 25

Adolf Jensen

Adolf Jensen: Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 25 (Erling Ragnar Eriksen, piano)

Adolf Jensen (1837-1879) hailed from a long line of musicians originating in Königsberg, now Kaliningrad. He had hoped to study with Robert Schumann, but the composer’s death on 29 July 1856 ended that plan. As early as 1857, Hans von Bülow wrote to Franz Liszt of “a young man named Jensen of great talent… full of enthusiasm for all that is beautiful, lofty and essential in art.” By Clara Schumann’s account, “Jensen was a profound and brilliant pianist with a wonderful touch.” In 1863, Hans von Bülow declared Jensen to be a “rebirth of Schumann’s Romanticism.” Jensen’s contact with Brahms dates from around that time, but according to a biographer “Brahms had recognised that a rather exaggerated Jensen cult reigned in the city of Graz.” In fact, Brahms said, “Jensen was immensely taken with himself and thought he was on the same level as Richard Wagner, although in a different fashion. His letters are full of vanity; he also had a habit of philosophising about his own things in his letters. I could simply not do that!” In 1863, Jensen composed a Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor and brought the work to Brahms for assessment. A flowery anecdote recalls, “When Jensen showed him his piano sonata, Brahms, in his frank, somewhat brusque manner, made the remark, these are four pretty piano pieces, but not a sonata.” Jensen became silent and Brahms went on talking about all sorts of other things. Suddenly, he noticed how poor Jensen’s tears were running down en masse. Brahms’ words had offended him so much.” Jensen did heed Brahms’ advice and he published the early sonata as 4 Impromptus, Op. 20. However, he was soon at work on a new Sonata Op. 25. As Jensen wrote to Brahms, “After I played you during our earlier get-together in Hamburg a sonata which consisted of four quite good pieces, I am sending you enclosed a ‘true’ sonata, taking the liberty of dedicating it to you. To what extent my view is correct that it is viable for your name to grace the enclosed F sharp minor Sonata – a title I could not forgo – you as a ‘sonata man’ will best judge.” Apparently, Brahms gave the work “high praise.”

Walter Rabl: Clarinet Quartet in E-Flat Major, Op. 1

Walter Rabl

Walter Rabl: Clarinet Quartet in E-Flat Major, Op. 1 (Wenzel Fuchs, clarinet; Genevieve Laurenceau, violin; László Fenyö, cello; Oliver Triendl, piano)

Johannes Brahms wrote to his publisher Simrock in 1896, “In any case, the best one is a piano quartet with clarinet. It’s said to be by Rabl, a pupil of Navrátil. I know little about the young man and his music, because I didn’t take a personal liking to him. Now of course I’ll keep my eyes on him and his piece.” That glowing recommendation originated from the 1896 composer’ competition held by the “Tonkünstlerverein” in Vienna. Brahms was the honorary president of that organisation whose declared aim was to counteract the music of the “New German School.” The 1896 competition was intended to advance the cause of chamber music with wind instruments, and a total of 18 works were submitted. The third prize went to Alexander Zemlinsky’s Trio in D minor for clarinet, cello and piano, but the winner was Walter Rabl. Brahms already knew that Rabl would win as he writes to Simrock, “I have more and more encouraging things to report of our prize-winner Walter Rabl. A whole pile of his music lies before me. He himself is coming to the festival in a few days and is about to earn his doctorate in Prague. The vote will take place on the 22nd; I believe he’ll take the first prize, though that is entirely beside the point. Everything is in the best hands of your Johannes Brahms.” Simrock did publish the Rabl Quartet as his Opus 1 with a dedication “to Dr. Johannes Brahms in deep respect.” Sadly, Brahms did not see the dedication in print as he died on 3 April 1897, only three months after the competition. Rabl, in turn, stopped composing altogether at the age of 30 and devoted his energies to conducting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter